One problem with taking social problems and re-framing them as individual responsibility is that it ends up blaming victims instead of pressuring root causes. This mentality creates a temptation to, for example, respond to the NSA scandal involving the government tapping into Internet traffic with something like, “well stop posting your whole life on Facebook, then”. Or less glib is the point raised many times this month that the habit of constant self-documentation on social media has made possible a state of ubiquitous government surveillance. The brutality of spying is made both possible and normal by the reality of digital exhibitionism. How can the level of government spying be so shocking in a world where people live-tweet their dinner? Perhaps we should stop digitally funneling so much of our lives through Gmail now that the level of surveillance is becoming clearer. Sasha Weiss writes in The New Yorker that,

Most of us react with horror to the idea that our online messages are in the hands of the government—in the sense of being collected in a massive stream of data and analyzed for suspicious patterns—but have no problem posting a photo of our kids, our wedding, or our lunch on Facebook or Instagram

This meshes with the surveillance studies literature that argues banal, voluntary, and habitual publicity makes us used to be being watched and thus less concerned about our privacy, ultimately leading us to become complicit with surveillance in general over time. The structure of digitally mediated life as it exists is indeed highly compatible with the surveillance apparatus. As such, it is very easy to use this scandal as an excuse to critique our culture of digital publicity, a culture where intimate spying is an inevitable outcome.

However, we should always be a little skeptical of thinking with such inevitabilities. The “resistance is futile” fallacy—the Borg Complex—takes for granted that everything that can be seen by anyone will be seen by everyone, and, in the process, fundamentally misplaces who is responsible for violations of privacy. At play here is that pesky, predictable trend of making individuals responsible for social problems: When the government—or in another news cycle, a social media company—violates user privacy, the seemingly-helpful response is to advise individual users to change how they behave.

Yes, if you use the Web less, the NSA will have less of you within their Utah zettabytes (aside: that’s a better team name than ‘Utah Jazz’). But the bigger point is that you should be able to use the Web without being spied on in the first place. To take this social problem, treat it as an inevitability, and then place responsibility back on the very individuals being violated does nothing to address the root problem: government overreach in the name of “security.”

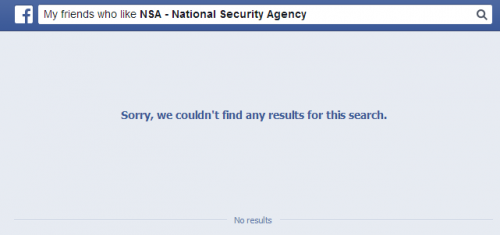

Breezily linking NSA spying with oversharing on social media misses that always crucial element: consent. Through the lens of consent, voluntarily posting photos of your vacation and the NSA having access to your emails are fundamentally different things. One does not inevitably need to lead to the other; in fact, we know that people who post more and are more public online tend to also enact more privacy measures. Privacy and publicity are not always antithetical, but often mutually-reinforcing. The goal shouldn’t be to ask individuals to stop living a digitally mediated life if they so choose but to make that mediation safer from violation in the first place.

That consensual exhibitionism makes nonconsensual spying possible may be technically right, but such a focus is morally wrong. Any response to the NSA scandal that ignores the importance of consent and instead places the responsibility for our own privacy, and the blame of its violation, back on us is untenable.

Nathan is on Twitter [@nathanjurgenson] and Tumblr [nathanjurgenson.com].

Lead image is cropped from a 1970 Newsweek cover, via.

Comments 2

Jeff Pooley — July 13, 2013

Though I'm not sure that Weiss was *blaming* exhibitionism as much as pointing to the irony of privacy concern in a sharing culture. And we have to admit that it's a pretty damn evocative example. The Mills-Snowden comparison should be taken as a provocation to think about the tensions and mutual reinforcements between self-chosen exhibitionism, the profit-driven sharing economy, corporate surveillance and the NSA. If anything, I found Weiss's neglect of the gender angle-- a guy calling for, and claiming, the right to privacy, with a girl performing herself in public--to be the real issue with the otherwise smart piece. It's a set-piece illustration of the differing expectations and freedom to maneuver that young men and women experience.

Cyborgology Turns Three » Cyborgology — October 26, 2013

[…] and publicity, how our approach is so often victim-blame-y from how we teach teens about privacy to how we talk about the NSA, to my issue with people claiming how glad they are they didn’t have social media when they […]