Oh, the irony…to find myself preparing to write about adaptations just months after the release of a motion picture based on a board game. A graduate student never had it so good: Battleship may not be a critical reflection of the delicate process of creating an adapted work, nor does it allow for the discussion of nuance and variation in the product of the adaptation process. But it is a rather wonderful example of the kind of derisive talk that swirls around them. Adaptations are spin-offs. Remakes.

Rehashed and retold, adaptations carry a stigma: the unoriginal story, not so much created as concocted. They are cobbled together from the source text – the original work, the one that was inspired by some spark of creative genius – and they can never be ‘as good as’ the story that came first.

To me, the adapted text is one that emerges out of an older, more established work. In the case of writing, it’s often a book that’s been made into a film, but it’s also novels that are based on older, more classic works. There is the original story – the source text. And there is the adaptation. Adaptations open up the original in a new way. A really good adaptation makes me read or watch the story with an awareness of the original source – it hangs in the back of my mind, and I compare what I know to be familiar or the same, and I am fascinated by what is different. Battleship aside, adaptations are original works of art – the same way a song that samples another is still music. But not everybody sees it this way…and so the debates go on, about what is art and what is not art, what is original and what is second-hand, and whether adaptations can stand on their own merits.

Adaptation as process: making old things new again

The adaptation is something that is poorly defined. Most commonly, an adaptation refers to a film or television show based on – and created from – a novel. The novel is the source; for many, the idea of an adaptation refers to the process that takes place when what is written in the novel is transformed and translated into film. It is called, at times, a transposition, and that refers to the movement of the source to a new medium – the translation of the text of a novel into the visual medium of film or television. The process of moving a novel to film is one best understood by most: most of us are aware of book to film adaptations like Bridget Jones’ Diary or Tom Clancy’s spy stories (A Clear and Present Danger, Patriot Games, and so on). But the adaptation exists outside of the ‘now a major motion picture’ genre, too – it can be simply the retelling of a story, still in the same novel-based format, but with a twist. A new way of regarding a character, perhaps, or the telling of a story from a new point of view in order to create a new way of seeing the source text. Seen this way, an adaptation is both a ‘new’ story and also the old. It is what Linda Hutcheon calls a ‘derivative’ work – not a secondhand or second-rate story, copied from an original, but a story that comes after the source. It is not, she insists, “slavish copying,” but instead part of an ongoing conversation between the original, source text and the new work that is being created out of it.

This ongoing conversation refers back to dialogism…which, in turn, goes back to Mikhail Bakhtin, long-dead Russian theorist. Key to the understanding of dialogism in adaptations is the idea that what is written in a novel or a story has a relationship to other stories and novels, and that they form part of a larger ‘conversation’ in literature. Bakhtin is not a theorist for the faint of heart: the “transmission and assessment of the speech of others, the discourse of another,” he writes, “is one of the most widespread and fundamental topics of human speech. In all areas of life and ideological activity, our speech is filled to overflowing with other people’s words, which are transmitted with highly varied degrees of accuracy and impartiality.” We talk and we talk, Bakhtin is saying, and when we write stories, our ‘speech’ – the things we write – overflows with the things other people have said – or written. We are influenced, constantly influenced, by the works of other writers. In all stories are the fragments of other stories.

As a writer, I understand this. The things I write are heavily influenced by what I have read and learned, and even more by what I have read and enjoyed. T. S. Eliot’s Tradition and the Individual Talent is essentially a happy nod to the significance of the works that come before a piece of literature, and how they collectively influence the works that will come after. Adaptation as a process, then, seems to fit in with the heavy-duty theorists: both Bakhtin and Eliot refer to this relationship novels and stories have with each other, and there is a strong sense that new novels and new stories have some sort of a relationship to these others.

The idea that texts can have relationships to other texts is, for me, a comfort. Writing is a solitary occupation; the feeling of having some connection to writers I admire gives me a feeling of companionship: I am not alone. But the adapted work is more than just the sense of connection to a prior novel or story. It is an acknowledged connection – a statement of influence and also the declaration of not only a ‘conversation’ between two texts, but the idea that the second text is somehow derived from the first. Derivative. Built from. Created by, or, perhaps, a new interpretation of the source, set down in a new way. Whether that new way is a new story or a new expression of the original story in a new medium – a movie, a game, an iPad app – depends on how the work has been adapted, and by whom. Hutcheon declares that in calling something an adaptation, “we openly announce its overt relationship to another work.” Even a ‘remake’ – an updated version of the original – is still an adaptation, because in creating it, there is a referencing of the original, and an acknowledged connection that lets the audience know ‘from whence it came.’

Remakes and adaptations are everywhere – and in these times of digital culture, they proliferate and spread more quickly than theorists like Bakhtin could have imagined. Julia Yu’s Goodnight Dune was adapted from a post seen on Reddit, and in turn is an adaptation of a children’s book – heavily influenced by David Lynch’s film version of Dune…in turn adapted from Frank Herbert’s novel. You could argue that Yu’s Goodnight Dune is parody, but it is also a derivative work – openly acknowledging its relationship to other texts, but also a highly stylized, original piece. There is a multi-voiced dialogism taking place, and yet it does not render Yu’s piece second-rate or second-hand. Not at all.

So the process of adapting a work – something that comes up in the academic and artistic world – is having that conversation, engaging in the dialogism that Bakhtin speaks of – doing it consciously, instead of letting it flow naturally around us. It is a deliberate choice. Where Bakhtin talks about the intermingling of things that are being written as part of a new story and the things that have been written in other stories, there is the sense that we are, as Robert Stam says, “mingling one’s own word with the other’s word.” An adaptation is, then, an “ongoing dialogical process,” Stam tells us – one where the derivative text is involved or engaged with the source text. The process of adaptation suggests that, as the new work emerges, we are privy to the conversation between old and new, rather than watching the old reproduced in a new and exact copy (Patrick Faubert, 2011).

If we are so heavily influenced by the words of others – oh, we are, says Hutcheon, for there is no such thing as original genius or an entirely autonomous work that transcends all others – then almost anything can be seen as an adaptation. Greek tragedies and Shakespearian plots (themselves reflective of the Greeks) are retold in countless ways. Classic novels are adapted for television and film or re-imagined in cross-genre results (Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, for example, or The Meowphosis). Popular fiction seems to move through the adaptation process at an ever-increasing pace (Twilight, Harry Potter).

The process of adaption suggests that the creator of the new work – the derivative work, the adapted work – is attempting to tell a story over again, but in a new way. These stories, says Hutcheon, change with each repetition, but they are still recognizable . We tell ourselves these stories in the form of adapted works because they are familiar and comfortable. We enjoy both the ritualistic remembrance of the original story and the sense of surprise that comes from its movement into a new form – like Texts from Jane Eyre which provides a fresh take on Rochester’s ‘attic wife.’

DID YOU LEAVE BECAUSE OF MY ATTIC WIFE

IS THAT WHAT THIS IS ABOUT

yes

absolutely

BECAUSE MY HOUSE IN FRANCE DOESN’T EVEN HAVE AN ATTIC

IF THAT’S WHAT YOU WERE WORRIED ABOUT

IT HAS A CELLAR THOUGH SO YOU KNOW

DON’T CROSS ME

HAHA I’M ONLY JOKING

Even without considering the enormous financial appeal of approaching successful stories in new ways, there is something to be said for a new work that holds a sense of fond familiarity.

We like the original so much that we want to hear and read it again and enjoy it again. Just not quite the same way.

Thinking about the adaptation as a product of the process

Is the product of the adaptation process…art? Is it literature? The process is an easier subject for the academic community to approach – the dialogism suggested by the relationship of the new work to the older original is open to all sorts of critiques and analyses. But is the adapted work as my friend would ask, as good as the original? Is it as artistic? The product of the process is a new work, but no, it’s not entirely original. It has been, after all, built out of something that existed before it – something that influenced its design. But it is also not the same as its source.

The process of adaptation is something we assume – we don’t see the process, and there is no tangible proof of that dialogical interaction between the source text and the adapted text beyond what we think we see. Though we can speak of the intertextuality of these stories – the intermingling and interwoven nature of these texts, building as they do off of each other as part of that cultural aspect of dialogism, we are making generalizations and assumptions about the overall process. We assume that dialogism is taking place because we see how the adaptation is related to the original text, but we don’t know, really, if this was the intention when the adaptation was being created. It is an inexact way of approaching adaptations, and this is, perhaps, one of the reasons the debate over them can be so heated. And because it’s difficult to get a sense of what goes on during the process of adaptation, we can’t know for sure if the writer or filmmaker really is trying for a new interpretation of an original source, or if they are just trying to produce a copy that’s as close to being a replica as possible.

But the product…the product is immediately available to us. Adaptations form a body of work that can be – should be, Hutcheon insists – seen as worthwhile on their own. The adaptation should not be seen only in light of the text it was adapted from. The product of the adaptation process is what is significant. Julie Sanders has written on adaptations, and she tells us that source texts – those primary novels and stories that adaptations are based on – are part of a “shared community of knowledge.” In simply calling a work an adaptation, the creator is giving a nod to this community, and also doing something more. For Sanders, an adaptation acknowledges a fundamental aspect of all literature: “that its impulse is to spark related thoughts, responses, and readings.” Bakhtin, I think, would agree.

The adaptation, then, is a way of seeing those realized in a new way. As a product of the process, an end result, it is the embodiment of all that is important about literature and art: the idea that you can read or see something and find meaning in a way that is unique and that has some effect on the you in a very individual way. Could we see an adaptation as something a reflection of that highly individual response to a novel, for example? Possibly. After all, even great works of art are inspired by other works of art – a kind of adaptation right there. I love film adaptations of Jane Austen novels. Why? Because the adaptation is a way of reinterpreting the original in a new and unique way. And we like seeing the story told again, but with a different emphasis.

We know that deliberate choices around interpretation of the source and its re-interpretation are made through the adaptation process because the end result shows us a new way to see a character or a situation. It is a powerful response to the way a story is first portrayed – whether that response is a respectful interpretation or a harsh condemnation. And this is where an adaptation can go from being a copy or replica to a new story that is just as important as the original…in its own way. The adaptation can be a transposition of the original story – shifting the work to a new medium (from novel to film, for example). It can be a story that is, essentially, a commentary on the original, intentionally or inadvertently, achieved through the alteration of the story. It can be an analogy that modernizes or changes the original text in order to shift the story to achieve some new goal decided by the adapting artist or writer. What is really the hallmark of a successful adaptation – and the reason for adapting a story at all – is the achievement of presenting the story in a new light, for good or for bad. Thomas Leitch writes on the idea of adaptations extensively, and he remarks that a really good adaptation challenges an audience to ‘test’ assumptions they have made based on their earlier experience of the original.

Encountering adaptations

Which brings me to the experience of reading Ann Patchett’s State of Wonder. It’s loosely billed as an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which I’d read (more than once, actually). Conrad’s story is a familiar one: Marlow heads to Africa to pilot a steamboat, seeking to enter the ivory trade. He arrives to find the steamboat in ruins; sunk on purpose, he thinks, though the station’s manager speaks of an accident. After enormous delays, he is sent up river to seek out another station and Kurtz. Bad things happen; Marlow comes back, lies to Kurtz’s fiancée…you’ve read the story. You know how it ends.

There are any number of ways to read it. Any high school or college student will tell you that they had to read it and write essays on the motifs of the story: on the imagery, on the colonial days of Africa, on the racism and the brutalities inflicted on indigenous peoples. The story is, for better or for worse, a classic, and it has been reworked since: Apocalypse Now is well-known as the film adaptation of the novel.

Next? Try Ann Patchett’s State of Wonder and read it as an adaptation of the original story. The novel features a female lead – Marina Singh. Like Marlow, she is sent into the jungle – this time, in South America – to find and bring back research being conducted for a pharmaceutical company. She arrives, suffers enormous delays (sound familiar?) and then eventually reaches the research station, where she finds that Dr. Swenson – the female equivalent of Kurtz. Swenson is a researcher who has been living among the natives, studying – and discovering- the source of their remarkable fertility. Women in their seventies having babies – it’s a miracle, really, and for a pharmaceutical research company, it’s the holy grail: “Pretend for a moment that you are a clinical pharmacologist working for a major drug development firm. Imagine someone offering you the equivalent of Lost Horizons for American ovaries.” As the novel progresses, Marina works to uncover the facts around the death of a colleague, Anders. He had been sent down ahead of her to accomplish the same task – an aspect of the novel that reflects an early passage in Heart of Darkness. Even the cover of the book is styled in a manner meant to evoke a kind of vintage feel that we associate with Heart of Darkness.

There is exploitation of the natives, though not necessarily on the same scale as we find in Conrad’s book. The story’s surprising conclusion (I won’t spoil it) hinges on the theme of fertility drugs and malaria drugs – the former incredible profitable for pharmaceuticals based in North America. The latter…not so much.

Depending on how you look at it, State of Wonder is a retelling of Heart of Darkness – there are a number of similarities between the books, and as you read Patchett’s story, you are aware of a sense of familiarity. I’ve read this story before. I think. It’s similar, but not the same. This is where the academic debates about adaptations – and yes, even the debates being had by mainstream critics and popular culture – really gets interesting. For as much as I’ve been talking about the idea of dialogical processes and the interlinked nature of stories and the importance of an adaptation having an identifiable link to the source text, they are not universally seen as something that should be different from the original. This, I think, is where my critics of adaptations come back into the picture. Their dislike of adaptations and characterizations of them as unoriginal works reflects the way most of us see an adaptation: that it should be as faithful as possible to the original story. When people say that they are disappointed in an adaptation, it’s usually because they feel that something fundamental to the story was missing – something that ought to have been presented in the adaptation in an expected way. What they are looking for is fidelity.

Fidelity is the idea that the second telling (or third, or fourth, and so on) should be true to the original. The adaptation should faithful to the original as possible – faithful as, say, a wife to a husband. If that seems like an outdated idea, it is. The adaptation is something that picks up the original story, but it tells it in a different way – and it is not a story that has to be held to the original’s version of how things happened. The beauty of an adaptation it’s not a complete copy of the original. It’s not a replica. If you wanted that, you’d go back to the original story. In the adaptation, the story is made new, made fresh, upcycled…and in the adaptation, you come to see the original in a new way, too. Think about reading State of Wonder and think about the politics of reproductive technology – how IVF and fertility treatments in the western world can feel like a baby-making industry. You’re thinking about the realization Marina has: that the pharmaceutical companies would only be interested in the fertility drug…not the potential malaria vaccine that the same tree bark can provide. It’s about money, and it’s about greed. If you read State of Wonder that way, do you think about its connection to Heart of Darkness? Yes. Do you start to think about the obsession for ivory that grips the people Marlow works for? Yes. Do you start to think about how a researcher who will stop at nothing to uncover the secret of ageless fertility – to the point where she experiments on her seventy year-old body – in light of the unceasing drive to control something that perhaps should not be controlled? Yes, you do. Do you see how this can be like Kurtz’s drive to control the natives? The company’s desire to control the African landscape? The story’s view of Western superiority in attempting to control an ‘under-developed’ landscape and its peoples – and its right to do so? Yes, yes, and yes.

You would probably think about these things if you know Heart of Darkness and remember those themes and motifs you wrote about in high school or in the college classroom. And the criticism – it really does seem to be a criticism – that comes through in Patchett’s novel is one that is meant to make you uncomfortable: that perhaps there are limits that should not be crossed. And that there are things that will not be done because they’re not profitable. And things that will be done because they are profitable, no matter the cost. Things that we should not do. Perhaps the things we drive ourselves to do for profit and for biological control over our perceived needs for late-life fertility are not so very different from Kurtz’s maniacal mission to transform the Congo for his own purposes.

Fidelity demands faithfulness. Without it, the adaptation can be characterized as inferior or second-rate – simply because it is not ‘true’ to the original. The original always does it better when you look at it this way. This is the way most people see adaptations, too: as stories that aren’t quite as good (or that are quite a bit worse) than the original. True fidelity may not even be possible: for every adaptation that tries to remain as faithful as possible to the original, there are scores of people who saw it, read it, or played it and said that it just wasn’t as good as it should have been. The idea of being able to perfectly capture what it was that made the original story a good one is something that is only theoretically possible. And from what we see of adaptation studies, it shouldn’t be the end goal.

If you were to read Patchett’s book from the fidelity stance, you’d be gravely disappointed. Though Marina-as-Marlow is an excellent story-teller, she does not bring a dying Kurtz back to civilization. Swenson, the Kurtz stand-in, survives. Marina comes back. She does not confront a widow; she brings a colleague thought to be dead back to his wife. There is no scene where Marina must lie about somebody’s last words to that widow. As a replica of the original, State of Wonder fails. As an adaptation, though, it is wildly successful. It’s all in how you look at it.

What we should be trying to see, when we look at an adaptation, are the choices made by the writer or the filmmaker (or the game designer, or the artist, or the poet…) as they work to reopen the original source. Do they try to stay true to the story – and if they do, is it meant to be satire? Or away to illustrate just how much they respect the original story? Or, as in the case of Ann Patchett, is it an attempt to bring the focus on a new issue – reproductive technology, pharmaceutical research, and corporate profits – by using a story that recalls the greed and perversion of the ivory trade? Is it an updated view of the older story, made to feel contemporary and fresh for new audiences?

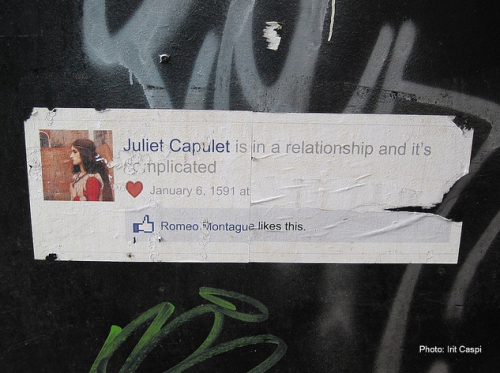

When you encounter an adaptation you read the two ‘stories’ together: the new story that is in front of you and the memory of the original story. You can’t detach the adapted text entirely from the source – here again is the idea that Bakhtin talks about, when he discusses dialogism: that there are always fragments of ‘other’ stories in any new story. Traditional adaptations – books made into film, books inspired by other books – are being enhanced by the new. Social media allows for dialogism to become enhanced. McSweeney’s Hamlet Facebook News Edition engages the source text but provides a critique of Facebook; further adaptations are seen in Facebook parodies of Romeo and Juliet (of which there are many – extending beyond the digital world to the analog). These works refocus the story in a way that draws attention to something new – a new aspect of a character, perhaps, or a critique of the way social media infiltrates and reframes events. These kinds of adaptations, augmented by social media’s reach and shared across networks, are the very height of dialogism. They are entirely multi-voiced; more than that, they are unabashed when it comes to the fragments of the original source that we find in them. Mash-up cultures that celebrate the appropriation of source texts essentially use adaptations as the vehicle of new cultural productions, new parodies, new satire.

These works refocus the story in a way that draws attention to something new – a new aspect of a character, perhaps, or a critique of the way social media infiltrates and reframes events. These kinds of adaptations, augmented by social media’s reach and shared across networks, are the very height of dialogism. They are entirely multi-voiced; more than that, they are unabashed when it comes to the fragments of the original source that we find in them. Mash-up cultures that celebrate the appropriation of source texts essentially use adaptations as the vehicle of new cultural productions, new parodies, new satire.

This is the power of the adaptation, really: that in reopening an original text, in seeing an older piece differently, new avenues for expression and criticism are opened. Maybe you value originality; maybe you like the idea that art is inspired but not influenced. For me? Art – and literature – is inspired. But it’s also something that builds on itself, that gives the opportunity to see the old works in a new way. Adaptation, it seems, it part of the ongoing evolution of creativity.

Heather Clitheroe is completing her MA in literary and cultural studies this year – studying zombie stories and the narratives of North American exceptionalism. @lectio or www.lectio.ca.

Comments 2

Well, this is exciting… | Lectio.ca — July 23, 2012

[...] Remember that term paper on adaptations? The one that was supposed to be written in a less academic tone and more like a magazine article? It made it onto the Cyborgology blog! [...]

No One Tells Stories Alone » Cyborgology — September 15, 2012

[...] draws upon influences of other fiction, sometimes merely in the form of homage and sometimes in adaptation. By the same token, when you tell a story to your friends about how you spent a weekend, that story [...]