One of Amazon’s many revenue streams is a virtual labor marketplace called MTurk. It’s a platform for businesses to hire inexpensive, on-demand labor for simple ‘microtasks’ that resist automation for one reason or another. If a company needs data double-checked, images labeled, or surveys filled out, they can use the marketplace to offer per-task work to anyone willing to accept it. MTurk is short for Mechanical Turk, a reference to a famous hoax: an automaton which played chess but concealed a human making the moves.

One of Amazon’s many revenue streams is a virtual labor marketplace called MTurk. It’s a platform for businesses to hire inexpensive, on-demand labor for simple ‘microtasks’ that resist automation for one reason or another. If a company needs data double-checked, images labeled, or surveys filled out, they can use the marketplace to offer per-task work to anyone willing to accept it. MTurk is short for Mechanical Turk, a reference to a famous hoax: an automaton which played chess but concealed a human making the moves.

The name is thus tongue-in-cheek, and in a telling way; MTurk is a much-celebrated innovation that relies on human work taking place out of sight and out of mind. Businesses taking advantage of its extremely low costs are perhaps encouraged to forget or ignore the fact that humans are doing these rote tasks, often for pennies.

Jeff Bezos has described the microtasks of MTurk workers as “artificial artificial intelligence;” the norm being imitated is therefore that of machinery: efficient, cheap, standing in reserve, silent and obedient. MTurk calls its job offerings “Human Intelligence Tasks” as additional indication that simple, repetitive tasks requiring human intelligence are unusual in today’s workflows. The suggestion is that machines should be able to do these things, that it is only a matter of time until they can. In some cases, the MTurk workers are in fact labelling data for machine learning, and thus enabling the automation of their own work.

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, like its namesake, exists at and reveals borders between mechanical and human, and sends ripples through our definitions of skilled and unskilled labor, as well as intelligent and rote behavior. Is MTurk work mechanical because it is simply following instructions? Is it human because machines can’t do it? What is the relation between the nature of these tasks and their invisibility, the low status of the work? Modern ideas of humanity, intelligence, and work come together to normalize the devaluation of MTurk work, and attention to the history of these ideas reveals the true destructive potential of the ideology MTurk represents.

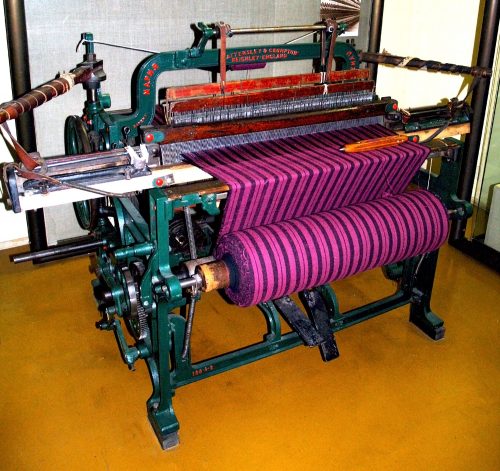

Dr. Jessica Riskin, a historian of science at Stanford University, points to 18th century France and Britain as an important source of Western notions of humanity in relation to automation. Technological progress was sparking philosophical debates about life and machinery, and industrialization presented labor as a common denominator placing humans and machines on the same spectrum. The skills and social standing of those whose jobs disappeared were not always common or low: textile work, which involved highly-skilled workers with generations of knowledge, was one of the first industrialized sectors. But automation devalued these roles: finding the upper limits of automation, Riskin writes, “simultaneously meant identifying the lower limits of humanity.” Automated tasks, or those bordering on automation, were not only lower in skill but further from what it meant to be human.

On the heels of industrial automation, there was also a change in thinking surrounding the relationship between intelligence and calculation. Until the early 19th century, many philosophers held calculation to be the essential nature of thought. Thinking was seen by many as a process of manipulating and recombining beliefs and values, yielding new ideas and actions the way a computation yields a result. Thus, intelligence and the ability to calculate were closely related: to think intelligently was to calculate well. But the division of labor separated the tasks of production into their smallest sensible stages, and this included calculation in making of maps, reference texts, and other products. Calculation became another task in the service of various kinds of production, done by menial laborers. It became clear that although it was a mental process, it could be carried out with great consistency by anyone who knew how to manipulate the figures. It was a “human intelligence task:” rote yet unautomated.

Dr. Lorraine Daston, another historian of science, credits the rise of rote calculation by low-status workers with causing calculation to lose its affinity with intelligence. Even before mechanical calculators were widely available, mathematical calculation fell from embodying the heights of intelligence and human thought to something akin to menial labor, barely intelligent at all. But unlike textile industrialization, it was not the existence of actual automatic calculation that lowered the status of the act, but the status of the laborers doing it. The fact that the work was being done merely by following instructions by ‘mechanicals’ as the undeviatingly obedient workers were called, seemed to rule out the possibility that what was being performed was intelligent and human, suggesting it was in fact automatic and inhuman.

The low status of computing as a job did not reflect the importance of the work being done. Many women in the USA hired to calculate during the World Wars were highly educated and vitally important to national success in the Space Race. The book and film Hidden Figures is perhaps the best-known example of the consequential work of human computers, a title we might apply to MTurk workers. Sexism lowered the status of human computers in the past, but so did the denial of computers’ opportunity to deviate from their instructions. Even though the human laborers were the best option, they too were ‘artificial artificial intelligence,’ a temporary stand-in for the cheaper, more obedient option on the horizon.

It makes sense to us today to conceive of rote, ‘automatic’ work as being low status. Socially we tend to value choice and judgment; we admire people who direct their own efforts, rather than being directed. Intelligent or not, important decision makers are valued above those who carry out orders.

The inverse of this tendency is the belief that automated work is less intelligent, and at first glance, it makes an intuitive kind of sense: tasks which require more intelligence are harder for humans to do and thus harder to automate. But it quickly runs into problems: the difficulty in automating a task is not a particularly good measure of the intelligence required for a human to do it. MTurk exists precisely for this reason. Consider chess, a quintessential example of AI triumphing over human intelligence. Chess took far longer to automate than weaving cloth, but we still had excellent chess playing computers long before we had any computer that could recognize a photo of an animal, something a child can do very easily – far more easily than mastering chess or weaving cloth.

The ideas we have today surrounding work, humanity, and intelligence are influenced by this history. But this history also reveals that what we deem low status work is determined by what we choose to value and not inherent truths about the work. The quality that matters most for automation is how algorithmic a task can be made. An algorithm is a set of instructions for proceeding from the beginning to the end of a task. Digital computers excel at following instructions; it’s all they do. They can follow more instructions than a human and do it faster, so any job that can be reduced to a set of instructions is just waiting for a program to be written to achieve it. This means that what determines whether or not a task can be automated has less to do with the humans currently doing it and more to do with how we define the job itself. Even calculation, the very definition of algorithmic work, was not always seen as opposed to human ingenuity. Work does not start out automatic; it is made automatic. This means work does not start out low status, but it can be made low status. We cannot turn calculation into a task that cannot be automated, but we can turn tasks that have always employed human intelligence, judgment, or interpretation into calculation; this is exactly what AI does.

Today, any job can be made algorithmic if we choose to understand it in computationally amenable terms. We can standardize and quantify desired outcomes and impose strict procedures known to produce them. We can digitize all the relevant objects and create models to handle unique cases, and perhaps most importantly, we can reject holistic, irreducibly complex, or unquantifiable goals.

Many jobs resist automation because they focus on unique human beings. What helps one person won’t help all others and the reasons why not aren’t always clear, nor is what qualifies as helping. But even these jobs can be changed to suit algorithmic approaches. Consider performance metrics, standardized tests, or the great common denominator: profit. In the age of big data modelling, if we decide that the goal of a job is quantitative, it can cease to require interpretation, judgment, or experience. It can become a number-crunching exercise of uncovering the patterns that determine success and recreating them: something high-powered computing tends to be far better at than humans. Today’s AI excels at creating models to suggest the conditions and actions needed to steer things towards well-defined goals. Human behavior is no exception: give a powerful AI program enough relevant data to learn from and it can recommend what to do in every case to “improve” whatever metric you want whether that is test scores, advertising engagement, or productivity.

As the division of labor continues to delegate more to computers, we must remember that those who are left jobless are not those with inherently less valuable skills or who are unintelligent. We are not only living through a period of technological change but also intense social change, when work is becoming more standardized. The less trust we have in individuals to decide what to do in their jobs, the more pressure there is to take away their discretion. As jobs allow less freedom and judgment on the part of workers, for the sake of optimized quantitative goals, they become more algorithmic, nearer to automation, less human, and lower status (to say nothing of the lost satisfaction and income).

In a way, human computers have not disappeared. More and more of us are doing algorithmic work computers may imminently take over. Jobs that once required human intelligence are increasingly being thought to consist of “human intelligence tasks” in support of a program. The status of the MTurk workers, of human computers, is the status of all workers when we reimagine work normatively as the execution of a program. When experience, intuition, moral feeling, affect, in a word humanity, becomes a problem to be controlled for, we are all unskilled.

Bio: Daniel Affsprung researches technology and its role in society, especially the visions of the human suggested and reinforced by technologies which imitate us.

Headline pic: Source