“Do you ever part it to the other side,” my girlfriend B asked one morning while I was futzing with my hair in the bathroom mirror. “I read somewhere that it’s good to part it the other way every six months so your regular part doesn’t pull wider.” Though it sounded like reasonable advice, the comment sparked an uneasy reflection – that the face I see in the mirror and in selfies is exactly reversed for everyone else…

A similar creeping feeling seems at play in people’s reactions to the Snapchat “gender swap” filters. “When the filter was released,” Magdalene Taylor recalls in MEL Magazine, “my social feeds were clogged with dudes talking about how hot they were with long hair and a feminized face. One dude even told Reddit about how he got caught jacking off to his.” Curious what might be behind these users’ apparent autoeroticism, Taylor asked psychologist Pamela Rutledge. “It appears that the gender-swap filter makes features more symmetrical, smoothes out imperfections,” Rutledge said. Taylor observes they make your eyes look subtly bigger, too. “So the filter isn’t necessarily an exact portrayal of a differently gendered self,” Taylor says, “It’s an idealized version of it.”

The gender-swap filters feel uncanny, but not in the usually uncanny valley sense. In contrast to a lifelike robot or CGI character that looks a little off, the eeriness of these face filters is more akin to meeting your doppelganger or a long-lost fraternal twin. On Facebook my cousin L posted a selfie with the ‘guy’ filter on and most comments from her friends suggested they didn’t realize she was using it.

This effect stems from these filters’ subtlety I think. The novelty of overt augmentation, like the dog filter or the many sponsored filters that turn your face into food items, seems to have peaked a couple of years ago, as the viral popularity of 2017’s FaceApp suggests. Using server-based neural nets, FaceApp made applying otherwise complex visual alterations, like ‘gender swapping’ or giving a formerly straight-faced selfie a grin, trivially easy. The app’s surprisingly naturalistic, near instantaneous results gave previously static faces a newly interactive quality, as Linda Besner examines in this essay. In it she recalls a designer’s visit to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, during which he used the app on original Rembrant portraits, “to brighten up a lot of somber looks,” in his words.

This participatory impulse Besner links to the history of Western art, specifically the transition from 17th century portraiture’s realism and 18th century Enlightenment’s determinacy to the 20th century when “interactivity between the viewer and the artwork became a dominant mode of creation.”

In the 1920s, Marcel Duchamp’s Rotary Glass Plates consisted of five plates affixed to an axis, and required the viewer to turn a handle to rotate them at speed. The whirling glass produced an optical effect as the afterimage on the viewer’s retina glued the separate pieces into a continuous circle. In Allan Kaprow’s 1964 event Eat, apples dangled from strings in a cave-like space, and visitors could choose to consume them.

FaceApp offers users a similar interactive thrill, whether from remixing historic portraits or their own previously frozen selfies.

Like how a remix or cover song anchors itself in listeners’ memories of the original, face filters usually ground their transformations by retaining some facial reference points (eyes, nose, jawline, etc). The gender swap filters in Snapchat push this resemblance deeper, almost subcutaneous, approaching special-effects makeup territory. And with some makeup artists appropriating sci-fi aesthetics in their everyday work, “special effects” may be a redundant descriptor.

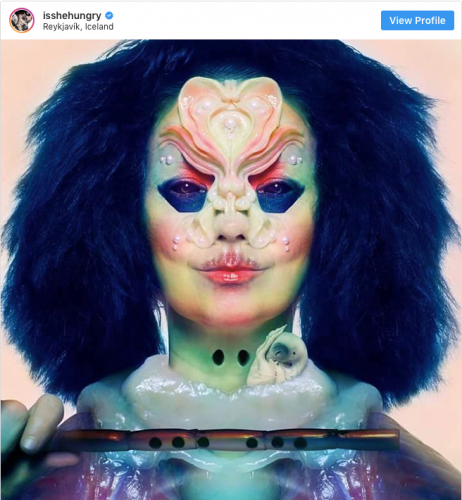

Indeed, it’s fitting that the same year FaceApp blew up coincides with the popular debut of Hungry, the makeup artist behind Bjork’s extraordinary look on her 2017 album, Utopia. “For the [album] cover, Hungry ‘painted and pearled’ the iconic singer,” Jade Gomez notes in this report (H/t Jay Owens), “and got an ‘orchid silicone appliance’ made by her personal mask maker, James Merry. … The image has a sense of eerily detached femininity …”

Hungry’s Instagram bio, Gomez points out, includes an apt phrase for her otherworldly style: “distorted drag.” It’s basically impossible to distinguish her clients’ skin from the makeup elements, a seamless blending that good face filters approximate digitally.

Between Hungry’s posthuman constructions and the more normatively human gender-swap filters of Snapchat, a number of independent filter designers are making their own distinct contributions. Ashley Carman highlights a few up and coming creators in this report. Their filters, many available on Instagram, range from bizarre – “a halo of golden hotdogs” – to what Carman calls “cyborg-esque.” The filters of Johanna Jaskowska exemplify this latter type, creating shimmery, liquid, vellum-like appearances.

In an interview with Vogue Italy, Jaskowska (from what I could get from Google Translate) relates face filters to fashion accessories: “A dress influences the behavior of the wearer. … [In the] same way, your attitude is different if you put on a puppy dog filter or one that makes you look shiny.” As well as taking cues from sci-fi movies, Jaskowska also draws inspiration from the dazzling effects on display in thriller director Henri-Georges Clouzot’s L’Enfer (1964).

Another designer, Aoe (@aoepng), prefers a public Q&A approach, developing multiple filters at once and posting their drafts to Twitter to gauge interest and collect feedback. A simple lipstick switcher, a hand-drawn aquarium with flitting fish, a second and third pair of eyes. “Rather than making things that I want to make, I try to make the next piece by referring to the ones I’ve submitted previously,” Aoe says (thanks, again, Google Translate). Just trying their filters on one after another gives me a basic impression of a designer’s creative inclinations, their learnings building on each other in a generative cycle.

Filters convey their designers’ artistic process and development. Yet as interesting as the artistry may be, these “informational qualities [of social images],” as Nathan Jurgenson argues in The Social Photo, “are a means to the end of expression.” As Aoe attests, they “promote communication without words,” and not only among users but between user and designer. “There was an overseas woman who gave the impression ‘Your work is interesting!’ She speaks English, I speak Japanese. There should be a language barrier there…” The visual, networked, filter-infused messages, in other words, helped to narrow the cross-cultural gap. This follows a key point in Jurgenson’s book: “Social photos take in the world in order to speak with it.”

Just as makeup, haircoloring or a different haircut can act as social lubricants that let us relate to others and ourselves in new, experimental ways, face filters can offer a temporary respite from more explicit and determinate forms of sociality, freeing us to interact more imaginatively and playfully with others and ourselves. And if their popularity continues to grow, it’s easy to picture future iterations of the technology giving users deeper input into the design process, with direct control to customize not one face but any number of appearances for a variety of social contexts and moods.

Though filters likely wouldn’t exist at all without the history and present influence of makeup and fashion, their use as a mediating tool for conjuring different kinds of selves also owes a lot to the avatar builder feature of contemporary videogames. Instead of explaining that, I’ll leave you with the following passage Vicky Osterweil wrote in her column Well Played which directly inspired me to write this post.

Video games involve the reiteration not only of stereotypes but also sorts of intimacy that can also be peculiar, counterhegemonic, and gender-bending. Many games — even ones like Saint’s Row or XCOM2, which appeal in other ways to masculinist colonialist ideas — feature whole-cloth avatar construction, with players sometimes able to literally sculpt the bones and contours of their character’s face and skeleton, allowing them to imagine and inhabit radically different bodies. Of course, these systems can work to reproduce and strengthen racist, misogynist, and transphobic tropes, restricting what kinds of hair styles, skin tones, facial hair, and so on are available and on what kinds of bodies. And they also may reproduce body-fascist standards of beauty, gender, and strength. But players’ ability to use these systems for their own pleasures, desires, and identities — along with the fan-fiction, modding, and original full-motion-video content that proliferate around games — opens up spaces of creativity, encounter, and expression that challenge or attempt to overturn these stereotypes.

Nathan is on Twitter.

Header image: left, Hungry’s Instagram (Blessed filter by per666y); right, Petit Anne (filter by Aoe)