I am an anthropologist of young people’s internet cultures and have spent the past 13 months learning (from scratch!) about K-pop fan practices on social media through intensive reading of academic literature, thoroughly combing through popular media, and immersing myself in various K-pop communities through digital ethnography. While I am by no means (yet!) an expert, in the past few weeks, I began to catalogue instances of misinformation in some fan network. Specifically, I traced the forms and mechanics of fan labour involved in generating or refuting such content. This interest was generated against the backdrop of a “war on fake news” in South Korea and the trend of “absurd”/”untrue” fan spoofs of idols on “fact accounts“.

At this exploratory stage, I am not yet concerned with verifying the information in these social media posts per se, but rather am focused on how young K-pop fans are innovating with creating attention-generating clickbait, instigating other networks of fans to signal boost their content, and labouring to clear up misconceptions or educate their peers about literacies around misinformation. This follows from my previous work studying how social media influencers are effective disseminators and persuaders of information in saturated internet climate, including their role in generating “subversive frivolity” and their savvy in “visibility labour“.

In this post, I present a brief overview of some of my observations focused on the fan-generated folklore, rumour, and potential misinformation pertaining to two incidents: 1) Bigbang member and soloist Seungri’s alleged involvement in a “major sex-video scandal” and “spycams” known as “molka” (parts 1 to 7), and 2) girl group Blackpink’s release of their YouTube record-breaking song Kill This Love, pertaining to platform politics and a Twitter hoax involving Starbucks (parts 8 to 10).

Screengrabs from the Seungri case study were taken from the “#Seungri” hashtag stream on Twitter on 22 March 2019. Screengrabs from the Blackpink case study were taken from the comments section of the Kill This Love YouTube video on 05 April 2019 and 08 April 2019, the “#KillThisLoveStarbucks” hashtag stream on Twitter on 06 April 2019, and the “#Blackpink” hashtag stream on Twitter on 10 April 2019.

*

1) Battle of the fandoms

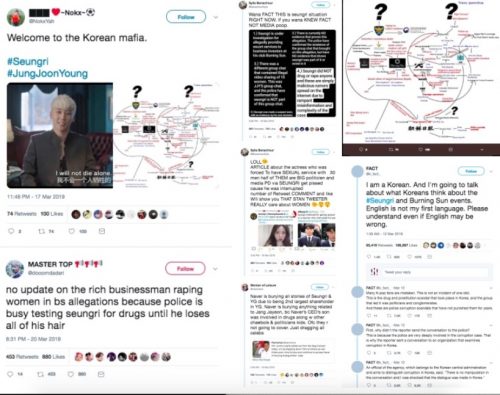

Upon the breaking news of Seungri’s alleged scandal, many fans immediately dissociated themselves from the artiste and expressed their disgust. But fans also emerged to share good testimonials about him and show their support:

Naturally, other (anti-)fans responded with more bad testimonials and went on sprees to block fellow Twitter users who expressed support towards Seungri:

And supportive fans began to speak out about the abuse they were experiencing from anti-fans:

In the midst of this schadenfreude, competing fandoms began to rejoice in Seungri and Bigbang’s downfall by using images and .gifs of their idols as memes:

Other fans criticised each other for capitalising upon other idols’ scandals to plug their own favourites:

*

2) Guilt by association

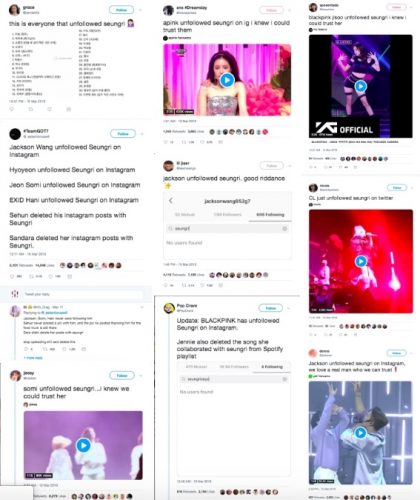

Fans began to celebrate other idols and artistes whom they claimed were unfollowing Seungri on Instagram and Twitter – an action that fans variously interpreted as other artistes verifying Seungri’s guilt, showing support to the victims, or wanting to avoid the drama altogether:

In response, other fans took the initiative to verify these claims by manually filtering through various social media following lists. They also called out the former group for exploiting the image of idols to generate RTs and likes on social media, and for tapping into the affective networks of other fandoms to generate publicity for their favourite idols:

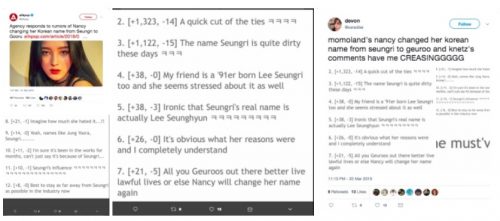

One idol who shared the same name as Seungri was also rumoured to have changed her name to dissociate herself from the incident, although competing reports state otherwise:

And the other members of Seungri’s band Bigbang were also thrust into the spotlight and scrutinised by the media and fans alike:

*

3) Fake news

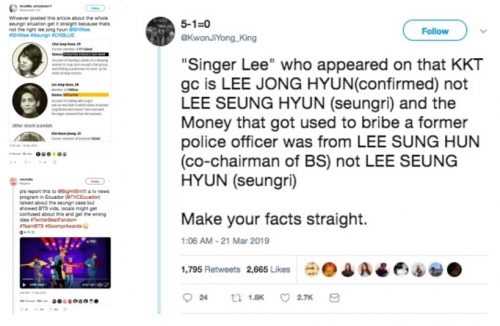

As news reports kept streaming in from various legacy and popular media outlets, some fans took to pointing out that fake news was being circulated as well:

Some of these malpractices were thought to be acts of mistranslation, and fans with native language skills or local knowledge offered to verify information and sources for other users:

Some news outlets were called out for using the wrong image and wrong name for the idols whom they were reporting on, casting even more doubt on the veracity of the wealth of “news” being circulated despite speedy updates on social media:

*

4) Law vs. Media persecution

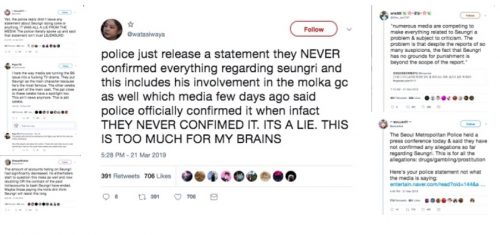

In the days following the scandal, the police regularly issued updates that contradicted with the claims circulated by various online media that were already taken to be factual. Fans thus pointed out that media outlets were also capitalising upon the scandal for generate traffic and viewership for their content, and pointed out that Seungri was first persecuted by the media before the law:

*

5) Amplifying and burying information

Fans felt that the overwhelming attention and focus on Seungri was a deliberate attempt to amplifying some information over others, in the hopes that a celebrity scandal will smokescreen or overshadow other more complicated issues involving a complex web of state officials, the police, and highly ranked corporate executives:

Some fans were promoting various attention generating trends:

While others pointed out these mechanisms of amplification and wanted to alter the narrative:

*

6) Spillover consequences

Some fans seemed concerned with the longer term consequences of the scandal, pointing out potential defamation suits, the en masse pre-mature assigning of blame, the larger impact on the K-pop economy, and emergent censorship across platforms and the media:

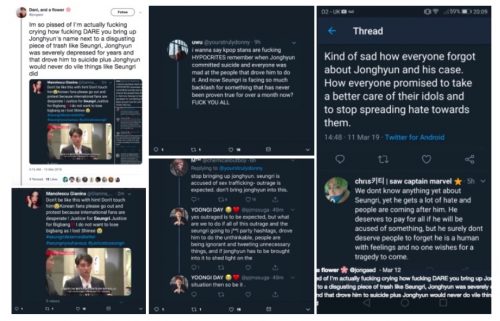

And others highlighted the potential impact of the scandal on the wellbeing of the artistes as persons, considering the culture of depression (and suicide) in the K-pop industry:

*

7) Para-entertainment

Alongside the severity of the scandal and the serious labour of fans and anti-fans, much of the content also carried a para-entertainment character where fans took the opportunity to insert their own content into streams of virality to generate visibility through memes, spoofs, and slash fiction:

*

8) Platform politics

The remaining part of this post will turn to the Blackpink string of incidents with their recently viral and record-breaking song Kill This Love that debut on 04 April 2019.

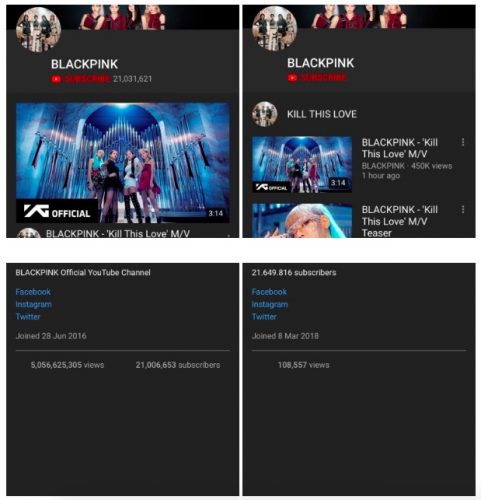

Following the release of the song, a small group of fans cautioned each other about imposter YouTube accounts that were siphoning Blackpink’s streams and views. In the following comparison, Blackpink’s official YouTube account is on the left while one such imposter account is on the left. Both accounts closely resemble each other if not for subtle verifying details: a) The official account’s subscriber count listed right next to the subscriber button (top left), but this is missing on the imposter account (top right). Instead, the imposter account attempts to replicate these verification markers by manually posting a subscriber count into the description box in another tab (bottom right). b) The official accounts About page lists their total number of views and the date the account was started coincides with Blankpink’s debut (bottom left), whereas the imposter account was started a year ago and has accumulated much fewer views (bottom right).

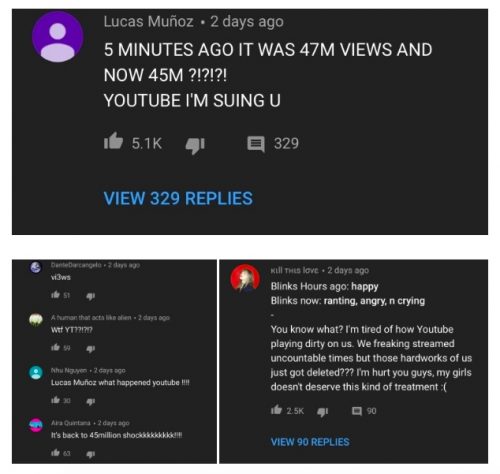

As the video ascended into virality, fans who were closely monitoring the video’s metrics were angered by the inaccuracy of the counters:

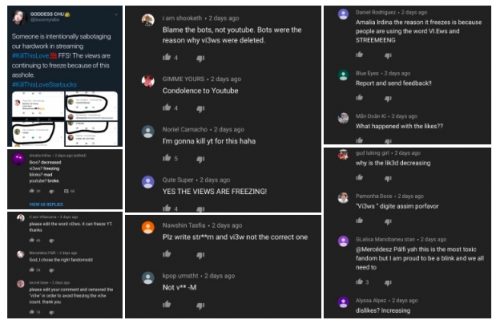

Other fans felt that the source of the ‘freeze’ was “sabotage” from anti-fans:

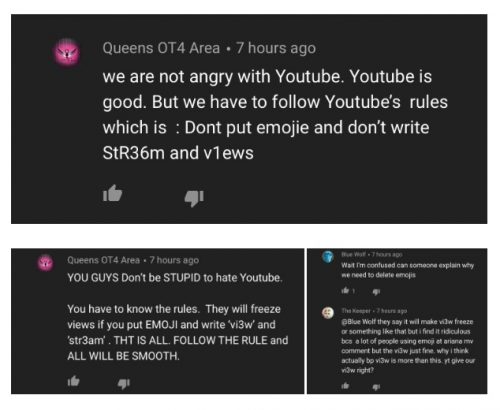

Allegedly, it is widely believed by fans that commenting with the words “view” or “stream” or even using emoji while commenting on a YouTube video would cause the YouTube views and likes meters to freeze:

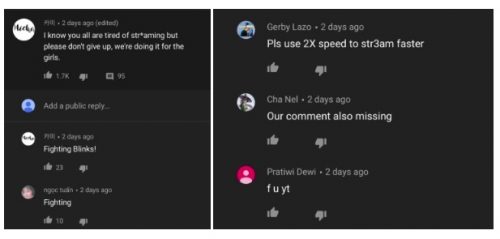

Thus fans began to ‘spread the word’ by replying to numerous comment threads, pleading with commenters to use l33t speak to evade platform censorship:

Alongside such peer-to-peer networked ‘education’, fans continued to double down on their efforts and strategised over more efficient ways to stream the video:

As Blackpink’s video broke music records, other conversation threads began to emerge on Twitter, accusing YouTube of falsifying the viewing history of its users. Some fans reportedly found Blackpink’s video in the ‘History’ tab of their YouTube account despite not having watched the video. Various discussions suspected platform fraud rather than a glitch. Fans who were familiar with YouTube’s various features claimed that the red bars superimposed onto the thumbnail of videos would indicate how much of a video was watched. Various comment threads thus noted the absence of said red bar on the Blackpink video that was showing up in their History:

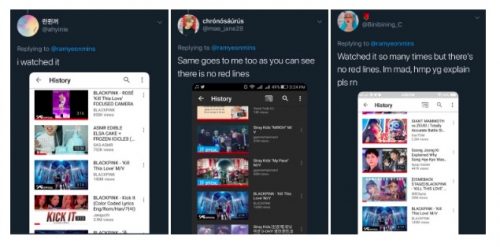

But still other fans disputed the ‘red bar’ theory, claiming to have watched the video (several times) but not registered that marker in their History:

*

9) Chainmail hoax

On 06 April 2019, a chainmail hoax broke out on Twitter claiming that streaming a Blackpink song would earn listeners a free drink from Starbucks. Rumour had it that users were to screengrab an image of themselves streaming Blackpink’s Kill This Love, post the screengrab on Twitter with the “#KillThisLoveStarbucks” hashtag, receive a voucher from a Starbucks social media account via direct message, and flash this voucher at any Starbucks outlet to redeem a drink:

Several fans then posted ‘evidence’ of their free drinks:

But many more fans who followed the instructions had not succeeded and were @mentioning Starbucks repeatedly, citing poor customer service or requesting for clarifications. Starbucks’ social media thus responded to the throngs of users with a template message that this was not a valid offer, and that they were investigating the incident:

And having personally worked in customer service, I give serious kudos to the various Starbucks social media staff for their labour in politely clearing up the misunderstanding with dozens and dozens of users:

Fans had various responses to Starbucks; while many realised this was a hoax (and acknowledged the genius of this strategy for increasing viewership on Blackpink’s video), still others called out Starbucks for bad customer service and threatened to boycott them:

Eventually, fans came to grips with the fact that the hoax was another strategy for signal boosting Blackpink’s video, as other Twitter users pointed out the spillover effects and stress placed onto Starbucks:

On reflection, many fans anti-fans felt that the stunt was “desperate”, “dumb”, and “problematic” (even if it may have succeeded):

*

10) Internationality

Across the various strategies listed above, a final observation I made was the range of international languages that fans were communicating in. I screengrabbed just a very small sample of such instances on Twitter, and continue to be convinced that the impact of K-pop fans, their fan labours, and their vernacular attention generating strategies and potential networks of (mis)information are not confined to South Korea or Asia:

*

A final remark from me:

Some of us may be tempted to brush these phenomena off as mere pop culture or fan practices. However, I find it more useful to frame these vernacular fan practices as strategies demonstrating effective science communication. These fans who are volunteering their time, labour, and expertise are using the vehicles of K-pop to demonstrate the production and circulation of misinformation, white noise, false flags, information amplification and burial, attention shaping, sentiment seeding, and clickbait on social media. They also display: a) the wit to tap across various interest communities whether through social media affordances or fan affects; b) the savvy to cohere across a variety of platforms with good knowledge of how each algorithm ‘works’; and most crucially, c) the rapid ability to spot, learn, replicate, and adapt emergent verification markers on social media, whether instituted by the social media platform or informally but widely acknowledged by fan cultures. In my current and future projects, I will continue to study such weaponising of popular culture as cultures of knowledge.

*

Dr Crystal Abidin is a socio-cultural anthropologist of vernacular internet cultures, particularly young people’s relationships with internet celebrity, self-curation, and vulnerability. She is the author of Internet Celebrity: Understanding Fame Online (Emerald Publishing, 2018) and co-editor of Microcelebrity Around the Globe: Approaches to Cultures of Internet Fame (Emerald Publishing, 2018). Reach her at wishcrys.com or @wishcrys.