The Instagram interface is changing so quickly and subtly all at once. For one, the app store on my iPhone constantly invites me to manually update my Instagram app in order to make those unsightly red notification bubbles go away. But the design tweaks and new features that are introduced each time come in small, user-friendly batches that I also learn to keep up and adapt.

In fact, although I was among the earliest adopters of Instagram in Singapore, where I have been conducting research on Influencers and internet celebrities since 2010, I don’t even recall what the original Instagram interface looked like. Do you? But perhaps the most logical explanation for the seamless uptake of each Instagram update is that the platform is merely institutionalizing into officialdom practices that have been creatively innovated and adapted by its users. The latest of these is Instagram’s multiple account prompt.

As someone who studies social media for a living, I have multiple accounts for different purposes on most dominant social media (if you’re really curious, that means 5 Instagram accounts including my pet project @thetravelingpingu). I used to manually log in and out of each account with its own specific email address and password, until February 2016 when Instagram enabled users to link two or more accounts under a single drop down menu.

I also used to painstakingly @reply brief thanks to each comment on every photo, but in December 2016 Instagram modeled after Twitter and Facebook and enabled a ‘heart icon’ as a new way of acknowledging comments on posts. The December 2016 also introduced a new feature allowing users to remove unwanted followers and delete comments, giving the impression of greater user autonomy and privacy.

In April 2017, the app introduced a new direct messaging update that now allows users to send “disappearing photos & videos along with texts & reshares” coherently in the Direct Message function. This encouraged dyadic and group messaging chats that further honed the illusion of seemingly private spaces in the otherwise public-facing, attention-grabbing, heart-hungry terrain of Instagram.

June 2017’s update gave users the opportunity to hide photos through the “archive feature”, reiterating the notion that privacy can be selectively assigned to content and exercised by users at their agency.

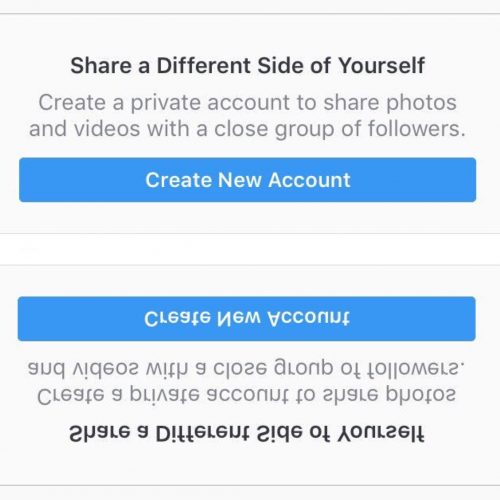

Last month, when I logged into my Instagram account, I noticed an intriguing in-app prompt. On my home page where I would usually scroll through my own pictures, a drop down banner read:

“Share a Different Side of Yourself

Create a private account to share photos and videos with a close group of followers”

As it turned out, Instagram’s latest project was to drive up their consumer base by encouraging users to create multiple accounts. And there are three main takeaways from this.

1) Instagram’s multiple account prompt borrows from the discourse of Finstagrams

By now encouraging multiple accounts through their new affordances and direction prompts, Instagram is bringing into officialdom the practice of Finstagramming. Finstagrams (Fake Instagrams, as opposed to Rinstagrams or Real instagrams) have long been proliferate among young users. Of the dozens of popular media articles reporting on Finstas, there are three emergent themes:

Firstly, Finstas allow young users to construct continuums of privacy by segregating their audiences. For instance, Finstas are where young people “hide their real lives from the prying eyes of parents and teachers”, or curate an “employable social media front”.

Secondly, Finstas allow users the freedom to curate several digital personae without the need for brand coherence. Young people may use Finstas to post “random streams of screenshots, memes and ugly selfies”, and dump content that is not congruent with their primary account so as to “protect [their] personal Instabrand”. In other words, this is “splintering as self-preservation”.

Thirdly, Finstas are a backlash against the picture-perfect pristine ecology of Instagram normativity, undoubtedly popularized by social media Influencers. Such separate, distinct, and unlinked accounts thus allows them to escape “the pressure to create a beautifully curated Instagram account”, rebel against the “overly stylized content shared by celebs and so-called influencers”, and expose the “artifice of normal social media”.

Multiple Instagram accounts are thus an overt signifier to young users that what once began as a subculture of subversive use has now moved into the mainstream, co-opted, promoted, and monetized by the platform itself.

*

2) Instagram’s multiple account prompt contradicts its parent company Facebook’s single account policy and real name policy

Facebook asserts that it is “against the Facebook Community Standards to maintain more than one personal account” since the social network is “a community where people use their authentic identities”. Shared or joint accounts are not allowed so users will “always know who [they are] connecting with”. Facebook also has a “real name policy”, which initially fixated on the notion that all users had a singular official/legal identity and are to use their “birth names” to register on the social network.

But amidst the difficulty of verifying third party photo IDs, and the backlash from queer communities and other marginalized groups for whom digital pseudonymity is paramount for personal safety and self-actualization, the company responded to criticism and relaxed its policy to allow users to use “the name they go by in everyday life” to “keep our community safe”.

Where parent company Facebook is adamant and imposing about the singularity and coherence of its consumers’ the digital personae, it encourages its app Instagram to diverge and splinter at the opposite end of the singular-identity spectrum by encouraging users to play with self-presentation and selective audiencing. But why is this so? The singularity of Facebook profiles serves as self-documentation for the company’s database of users. A “real identity”, “real name”, “real life” policy ensures that Facebook is able to facilitate messages and ads from its clients efficiently and effectively to its targeted audience as appropriate.

On Instagram, however, the primary motivation for the network appears to be less the archival of membership and more the generation of digital content, no doubt stimulated by the free labour of its users. While Instagram does not legally own any content posted, its terms of use grants them the “non-exclusive, fully paid and royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license to use the Content that you post on or through the Service”. Multiple Instagram accounts per user thus generate more free digital content for the network’s commercial use.

*

3) Instagram’s multiple account prompt verifies the rise of calibrated amateurism

In its drop down bar prompt, Instagram’s strategically worded key phrases “different side”, “private account” and “close group” suggest that users have long been practising strategies of self-presentation on digital media, in spite of its “authenticity rhetoric” on parent company and platform Facebook. It supports the need for scholarship on digital identity to go beyond simplistic dichotomies that the “online” is “fake” and the “offline” more “authentic”, given that all self-presentation in digital and physical spaces is curated.

In fact, in the age of picture-perfect, luxury-oriented, hyper-feminine Instagram Influencers who have dominated the Instagram economy thus far, authenticity has become less of a static quality and more of a performative ecology and parasocial strategy with its own bona fide genre and self-presentation elements. I have studied the rise of such performative authenticity as “calibrated amateurism”, which I define as a “practice and aesthetic in which actors in an attention economy labour specifically over crafting contrived authenticity that portrays the raw aesthetic of an amateur, whether or not they really are amateurs by status or practice, by relying on the performance ecology of appropriate platforms, affordances, tools, cultural vernacular, and social capital”.

Calibrated amateurism is a modern adaptation of Erving Goffman’s (1956) theory of scheduling and Dean MacCannell’s (1973) theory of staged authenticity.

Goffman argues that on stage as in everyday life, performers may engage in “scheduling” to segregate different audiences from each other. This is so that only one aspect of a persona is presented as required. Performers may also obscure the “routine character” of their act and stress its spontaneity so as to foster the impression that this act is unique and specially tailored to whoever is watching. In this space, there may be some “informalit[ies]” and “limitations” in “decorum,” which Goffman defines as “the way in which the performer comports himself while in visual or aural range of the audience but not necessarily engaged in talk with them”. However, this “backstage” is seldom as spontaneous as it postures to be but is instead a deliberate effort to manufacture a “back region.”

MacCannell studied tourist settings in similar back regions and describes tourists’ pursuit of authenticity as complicit in the actual manufacturing of a backstage that does not exist. He writes that “[j]ust having a back region generates the belief that there is something more than meets the eye; even where no secrets are actually kept, back regions are still the places where it is popularly believed the secrets are… An unexplored aspect of back regions is how their mere existence, and the possibility of their violation, functions to sustain the commonsense polarity of social life into what is taken to be intimate and ‘real’ and what is thought to be ‘show’”.

Combining these two classical theories for a contemporary digital phenomenon, internet users today also partake in deliberately curated and intentionally public forms of backchanneling through Finstas and multiple Instas. Multiple accounts encourage followers and viewers to engage in cross-platform hopping, watching, and matching. They imply that we all have backstages and hidden secrets on display on parallel platforms, if only our audience knows where to look and how to look for these easter eggs. Thus emerges a new game in the attention economy where the pursuit is no longer some semblance of authentic disclosure, but a competitive investigation into and comparison of the different strands of selfhood that a single user may put out on multiple platforms through multiple through multiple usernames promoting multiple personae.

In short, Instagram’s multiple account prompt is essentially the antithesis of Facebook, where digital identities are fragmented rather than singular, diffuse rather than collective, and playful rather than static. So how many Instagram accounts do you have?

Dr Crystal Abidin’s new research on “calibrated amateurism” is open access on Social Media + Society, which you can download in full here.

*

Dr Crystal Abidin is an anthropologist and ethnographer who studies young people’s relationships with internet celebrity, self-curation, and vulnerability. Reach her at wishcrys.com and @wishcrys.