Two very different kinds of thoughts were running through my mind on the way to Leipzig to the BMW factory and on the way back. On the way there, I was thinking about how and why factories are relevant to the study of artificial intelligence in autonomous vehicles, the subject of my PhD; and on the way back I was thinking about the work of Harun Farocki, the German artist and documentary filmmaker who left behind an astonishing body of work, including many films about work and labour. These two very different thought-streams are the subjects of this post about the visit to the factory. They don’t meet at neat intersections, but I think (hope) one helps “locate” the other.

BMW is a German car company that is working on ‘highly automated driving‘ (although the Leipzig factory we visited isn’t making those cars at present). I’m doing a PhD that will – someday – suggest how to think about what ethics means in artificial intelligence contexts, and will do so by following the emergence of the driverless car in Europe and North America. One part of what I’m doing considers a dominant frame that has emerged around ethics in the driverless car context: ethics-as-accountability. In the search for the accountable algorithm in driverless cars of the future, I went to the BMW factory to see where the car of the future will come from. Who, or what, must be added to the chain of accountability when the driverless car makes a bad decision? Who, or what, comes before and around the software engineer who programs the faulty algorithm?

I discovered something else more vividly and strangely digital than the car – the automation of the factory itself. In fact, the autonomous, intelligent car receded into the background and what emerged was a demonstration of scaled up, cybernetic thinking resulting in a factory that is shaped by logistics, which as Zehle and Rossiter put it is the ‘organisational paradigm’ of cybernetics:

The primary task of the global logistics industry is to manage the movement of bodies and brains, finance and things in the interests of communication, transport and economic efficiencies. There is an important prehistory to the so-called logistics revolution to be found in cybernetics and the Fordist era following World War II. Logistics is an extension of the ‘organizational paradigm’ of cybernetics […] Common to neoliberal economics, cybernetics and logistics is the calculation of risk. And in order to manage the domain of risk, a system capable of reflexive analysis and governance is required. This is the task of logistics.

The factory has become an infrastructural node, rather than the primary theatre of action; as part of a multi-nodal software program that determines the movements of people and things, rather than a point in a linear assembly line. To mix metaphors, logistics is the brainchild of cybernetics, serving as a kind of mental model to with which to think about the processes of production in the face of rising costs, rising demands and complex risk paradigms. So, conversations about “smart factories” are not about robots taking away jobs, which is a limiting approach to the topic; it perhaps more that people’s jobs in the smart factory become integrated into and are determined by software programs that determine where people, money, raw materials, ships, and eventually power itself, are to go. In what may sound a little dramatic, things like cars have (to) become software in order to be produced.

The ‘logistical turn’ has gained prominence as computer programs have come to be their the main design environment and control mechanism in manufacturing. Ned Rossiter, explains why logistical technologies are important: that “logistical technologies that measure productivity and calculate value” intersect with financial capital and supply chains, to result in a governance regime of standardization.

The factory features prominently in the origin story of the theories we love, cite, and lean on. The machine of Capital, the industrial machine, commodity fetishism, the culture industries: these are ideas that come to us, primarily, from observations of workers and conditions in factories. Factories and making convey significant symbolic power. As Merkel famously retorted to the then-Prime Minister of Britain, Tony Blair, on what Germany’s secret sauce is: “Mr. Blair, we still make things.” But what does it mean to make things in conditions enabled by the internet, particularly unwaged work and new forms of labour wrapped up as ‘play’ and leisure? Trebor Scholz,edits Digital Labour: The Internet as Playground and Factory which offers a deep read into the many dimensions of what digital labour means. He says in the introduction: “there are new forms of labour but old forms of exploitation.” In an earlier time, it was perhaps less complicated to isolate where the exploitation comes from; in a time of ubiquitous computing, you have to pick away more carefully to reveal where it is.

In 1895, the Lumiére brothers made one of the world’s first films, Workers Leaving The Factory, in which workers are shown exiting the brothers’ photographic products factory in Lyon, France The film is a jumpy 45 seconds long on a 17m long film reel, a reminder of a time when it was apparent that people were technology, the first movie-making machines being hand-cranked projectors.

One hundred years later, German filmmaker Harun Farocki, asked: where were the workers going? “To a meeting? To the barricades? Or simply home?” and made a documentary researching the history of that film. Twenty years on and still intrigued by this film, Farocki and his co-curator, Antje Ehmann, presented Labour in a Single Shot, an exhibition of more than 200 single-shot 1-2 minute films about labour created through workshops in 15 cities around the world. The films are charming, whimsical, and are about varied and diverse kinds of labour: dog grooming, child care, industrial manufacturing, leather curing, surgery, taco delivery, water delivery, teaching, building inspection, security, tailoring, piano tuning, shoemaking, data centre management, and so on.

Labour is as much about capturing different kinds of labour as it is about filmmaking. All cameras are fixed giving a single perspective, the kind of thing we’re more likely to equate with CCTV visuality. In one film from Rio de Janeiro, we see a woman minding a little girl in a pink dress playing in a sandpit in a park in a garden. The child goes down a slide and obviously falls because we hear her wailing and the nanny runs out of the frame. We hear the child’s loud cries, and the nanny attempting to soothe her, all the while, the camera remains fixed. A few seconds later we see a child in her nappy, now muddy with sand, storming back into the frame and crying, the nanny scurrying behind her with the pink dress. What happened off camera?

Labour is a series about work that goes unrecognised as work, work that is both material and immaterial, mobile and fixed, routine and irregular, and the various contexts of sociality, camaraderie and the self in work. We see what it means to pay people for doing mundane and boring things like stacking clothes in a factory, or difficult things like scaling buildings, or moving the carcass of a dead cow, or things that are difficult to value, like teaching music. The mind seeks to draw equivalence between these activities and it is sobering and challenging to see where and how ideas of equivalence between different kinds of work break down. Always deeply politically invested, Farocki and Ehmann, want the viewer to be charmed and discomfited in equal measure, it would seem.

Back in Leipzig, a senior manager tells us, “Industry 4.0 is about smart logistics.” This isn’t just a piece of business jargon however; the manager said he did not like the idea of “smartness” and “4.0” but seemed to suggest it was baked into the design and operations of the factory; smartness was a sort of inevitability, it seemed. We heard many managers, at different times, talking about “the future” saying they were “ready” and “prepared to face it”. I wondered if this had something to do with the realities of autonomous vehicles that would come in “the future”? They just smiled in response.

The factory’s former chief engineer, and now- BMW board member, Peter Clausen says “communication was the implicit assumption underlying the design of this building…”; and eventually, “there is a central nervous system thinking in the flow of the building….” He hired the late Zaha Hadid to build a factory re-imagined as a place that would respond, seamlessly, to distant nodes of control and regulation. Thus, the words “flow”, “future”, “distribution” are mentioned often in talking about the architecture of the plant in relation to the production of cars. These and other ecology metaphors familiar to cybernetic thinking kept cropping up.

While we were walking around the shop floor, a manager told a story about BMW’s electric car, the i3, as we milled around its engine proudly on display. He said that in building the electric car they didn’t just replace the traditional combustion engine with an electric one; they actually invented a whole new car around an electric battery. They made “working from the outside-in” sound more intuitive than the oft-heard reverse, “from the inside out”. What this anecdote suggests, I believe, is that they wanted to, or had to, change how they saw production itself, to move away from the idea and practice of production as something linear. In a snarky comment to distinguish themselves from Google, someone said referring to the software company, “they’re a software company – they think about communication and then build a car around it.”

Here it seems that communication is embedded far deeper. The factory was designed in response to people’s communication flows. They measured the number of steps taken for one team to reach another, and the ways in which teams talk to each other through the production life cycle, and the different workflows of who talks to who, and when they need to talk to each other. One of the senior-most managers at BMW delighted in revealing that he receives less email than the visiting academics; he said he gets up and walks over to people to talk to them, thus reducing his email footprint: “email is asynchronous communication; talking to people is synchronous.”

Flow extends to how the shop floor merges with office space. Cars assembled in one part of the factory called the Body Shop travel along raised gantries right through the factory on their way to being painted and fitted out in the Paint Shop. You can be checking email, or talking to a coworker at the water-cooler, and have an unpainted shell of a i3 glide past overhead. The sides of the transfer gantries are lit in purple; we snickered about this as a tribute to the recently departed Prince. You could be forgiven for feeling like you’re on the filmset for a bad sci-fi film set from the 1930s. Or a music video from the 1980s.

People flow; there is an attempt to adjust traditional hierarchies into something nominally flatter in certain respects, and possibly shaped by mainstream notions of equality in German society (there are some deeply troubling notions of who a German is, however)The plant is built with one entry and one exit, so everyone -managers and workers and all levels of staff – enters and leaves through the same door. Everyone eats at the same cafeteria. Human Resources and Corporate Communications departments sit on the ground floor, by the cafeteria and the entry, and everyone has to walk past them.

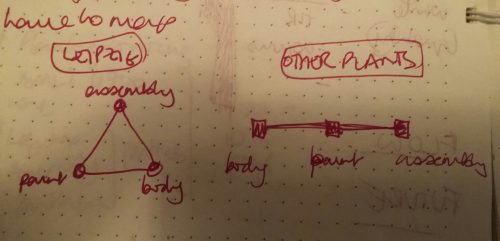

The jewel in the factory’s crown is Clausen’s “finger concept”.. Traditional ideas of the assembly line are, well, linear. Imagine, instead, a single line bending to form a triangle before what was the ends of the line become the middle and the middle breaks apart to form the new ends of the line. This is, almost literally, what this factory does; what it means is that production can integrate new elements or processes without getting disrupted. For example, automation in cars means that new automating machines need to be introduced into the line. How do you enlarge the backbone of production without moving anything up or down the line? There is no way you can shut down a plant like this for more than ten days to change production processes. The answer: the factory has to expand and contract on demand. Thus the “finger” is an architectural design feature in which the physical layout of the plant can keep being extended by building new sections to integrate new machines, storage areas, supply chain entry points, and so on. Organic metaphors of ‘growth’, ‘marriage’, ‘body’, and ‘evolution’ are key to the description of such responsive architectural design.

But this is not about the triumph of welding social science into industrial design, nor about spatial design theory in corporate brochure copy. It is about the relentlessness of cybernetic thinking that promises comfortable, soft orderliness almost as a sort of counter-point to the very disruption it stimulates, with its flows, nodes, and self-organising, feeding-back loops, constantly seeking order in systems that may be complex, glitch-ridden, or creaky. The disruption and innovation, seen in light of rising costs and demands, are oddly, about standardization itself; the old factory again. Decision-making is not inspired, but faster. Algorithmic regulation resulting in the financialisation of labour, and the demands on physical infrastructure, and its people, to become like components of that system, smooth and flowing, to become data.

In 1990, after the fall of the Berlin wall, Farocki made How To Live In the FRG, a series of mock ‘training seminars’ for workers, from strippers to nurses, to adjust to a new life in a neoliberal world of a “relentless scripting” of interaction where human and commodity are “machined” to assume “maximum dependability”. For example, in the scenes with the stripper, you are shown a woman’s midriff and hips against a dimly red light-lit stage, very typically ‘stripper’; and a male voice off-camera. This un-embodied voice instructs the abbreviated woman on how to move her hips suggestively, how to slip out of her panties, and how to look more seductive. It is pedantic, funny, and awkward.

There is something that happens in the smart factory, that isn’t quite different from the not-smart factory: the worker is known through her relations to the finished product, and things in between get obscured. Erich Hörl reflects on how ubiquitous computing results in the “becoming-ecological” of media and creates displacement of workers, saying that work then was a “privileged action that focused on results and finality and obscured relations, mediations, and objects. Without direct dialogue, humans and the world or nature were placed in relation to the object, but only indirectly via the hierarchical structures of the community”. I read the smart factory as a continuation of the old one, in this sense. In the smart factory, the loops and flows of information supersede everything else, making the fact of mediation, the design, objects, and the people disappear; the flow is the thing.

The Farocki films I was thinking about on the train back from Leipzig keep digging at those obscured relations, mediations and objects, urging power out into view, quietly, sometimes grimly comical, and always with purpose. The scene with the stripper, like others in FRG, is rich in the minutiae of what work entails. In an issue of the journal e-flux dedicated to Farocki after his passing, the editors say:

With Harun’s precise scrutiny, an intimate world of techno-social micro-machinations comes to life. When an automated gate closes and latches, Harun is there. When looking into the LCD screens replacing rear view mirrors in cars, he is there. He is there when we address a colleague at work with a certain title.

Maya Indira Ganesh is a reader, writer, researcher and activist living in Berlin, Germany. She is working towards a PhD about ethics and technology at Leuphana University, and is Director of Research at Tactical Technology Collective. She has worked with feminist movements in India, and continues to at an international level through her work on Tactical Tech’s Gender & Tech project. She’s on Twitter as @mayameme; find more at Body of Work.

Comments 2

dmf — October 31, 2016

https://installingorder.org/2016/10/28/complexity-management-and-the-information-omnivores-versus-univores-dilemma/

dmf — October 31, 2016

nice take on cyborgology as environmentality for more see:

https://installingorder.org/2016/10/28/complexity-management-and-the-information-omnivores-versus-univores-dilemma/