Content Advisory: The following contains references (including an embedded video) to sexual assault and misogyny.

At the end of the panel following Angela Washko’s artist talk at UC San Diego’s Qualcomm Institute, there was time for two questions. The first came from a man in the audience who jumped to the mic in order to frame the artist’s work in the inevitable deluge of AR, or augmented reality technology (think holding up your phone and seeing a Pokestop where another passerby might just see the local Walgreens). The audience member, a computer scientist from UCSD, wanted to know what would happen once we “throw away this technology that we’re tethered to.”

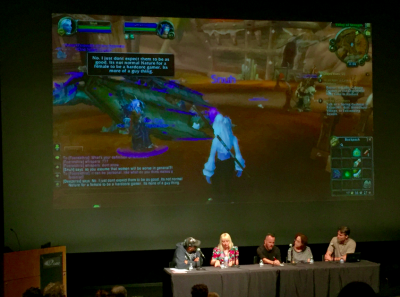

Washko had begun the evening with a presentation about her work, starting with her performances in World of Warcraft, wherein she goes to some of the most popular areas in the game to perform certain actions or ask other players about issues like abortion and feminism. I found the piece both charming and troubling: at one point, Washko’s avatar orchestrates a conga-line type dance party in a field where orks and trolls frolick in harmony while acting like chickens (just trust me, go to 25:00 in the video below). During the WoW interviews, the situation was a bit less whimsical. In Washko‘s words:

I realized that players’ geographic dispersion generates a population that is far more representative of American opinion than those of the art or academic circles that I frequent in New York and San Diego, making it a perfect Petri dish for conversations about women’s rights, feminism and gender expression with people who are uninhibited by IRL accountability.

She finished her talk with her most recent project, The Game: The Game, a choose-your-own-adventure type, compiled using only footage and quotes from pick up artists’ how-to books and DVDs (the DVDs are prohibitively expensive so that those seeking only to critique the PUAs avoid doing so; per Washko, “I got a grant, so I bought them”). By this point, the audience was already familiar with both her preferred subjects of interrogation and also the extremely brave way she places herself at risk for the sake of her work. For her UCSD MFA thesis project, Washko convinced notorious pickup artist Roosh V to agree to a video interview. This was around the time during which #gamergate was garnishing a great deal of media attention and Roosh V had dedicated a section of his site’s forum to the type of mysoginist discourse that accompanied the hashtag on other various platforms. That Roosh V would agree, then, to be interviewed by a self-declared feminist and artist is a testament to Washko’s persistence; as part of the negotiations, she sent a photograph of herself to the PUA, allowing herself to be judged worthy of Roosh’s attention.

While Washko’s interview with Roosh is itself an important piece, the first clip from The Game: The Game that we saw was from a different pick up artist who goes by “RSD Julien”. In this clip, Julien begins by explaining that placing the word “now!” at the end of any declaration sets you up as an Alpha amongst Betas (“Afterparty. Now!”, “Cab. Now!”). Admittedly—ashamedly—I found myself chuckling. A serious-looking man yelling “now!”, declaring this would get him laid, the camera cutting between a head-on and side shot. It looked like a Real World audition tape. My lighthearted reaction quickly receded, however, as a significantly more troubling shot played on-screen: a hidden camera captures Julien forcing kisses onto an unwilling victim, shaming her into leaving her friends to get in a car with him, and finally carrying her away off camera. At this point, I was embarrassed for having ever chuckled.

During the panel after Washko’s presentation, Benjamin Bratton asked the artist who The Game: The Game is for, “who should be playing this?” Her answer was simple: men. Femme-presenting women, she noted, experience the goings on from the narrative on a daily basis, they need not be reminded. Men, on the other hand, usually end up playing the game twice, “to see what actually happens if they try and go along with the pick-up artists.” Immediately, I began to consider John Rauch’s Cinema of Cruelty, an adaptation of avant-garde playwright, Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, a mode of performance which assaults the audience, garnering great affect from their subconscious. In Sensuous Scholarship, Paul Stoller, writing about both Artaud and Rauch, notes that, “In a cinema of cruelty the filmmaker’s goal is not to recount per se, but to present an array of unsettling images that seek to transform the audience psychologically and politically” (120). Washko’s work did just that; the anxiety being produced by her work in that room was palpable.

And so we return to the first question asked of the artist: “what happens when AR takes over…the game is everywhere…when we are autonomous and the possibilities are endless?”

Not unsurprisingly, the question was fielded first by panelist Jurgen Schulze, another computer scientist and professor at UCSD, who presented a utopian vision of being able to paint the characters we wish to see on the individuals around us. We will make our worlds whatever we want them to be. Bratton followed up with a refreshingly realistic view (albeit in the same obfuscating jargon with which he writes), describing an AR-laden world “wherein whatever form of cognitive totalitarianism you happen to subscribe to becomes literally the perceptual platform by which you sort of work through and then the incommensurability of the gamifications of interaction becomes that much noisier.” This felt more like it. Afterall, Washko had already explained that 55% of female avatars in WoW are actually played by men who often say that they prefer to look at a woman’s backside running around rather than a man’s. Imagine, then, these men with their AR goggles, painting whatever fetish they wish all over the town, reproducing an already overbearing sense of ownership over the objects, places, and—of course—people around them, but this time, with a convenient and dualist explanation that “it’s just a game” or “it’s all virtual.”

Fortunately, the second audience question left us on a much more productive note: a graduate student asked Washko to discuss the various points of entry and venues outside of art or academic circles in which she has performed her WoW actions. Her response—that she considers the performance of her work in WoW itself as “outside the art-world context”—was a quick one, but it was the question that left us with a critical reminder. Throughout her work, Washko has continuously used her body—be it a photograph, avatar, or her actual presence in a space—to facilitate and gain access to critical discourse within and surrounding technologically mediated spaces. One need only look at her Twitter mentions to even begin to understand what sort of sacrifice this represents. Panel moderator Ricardo Dominguez (who is also an activist, professor in the Visual Arts department at UCSD, and one of the founders of the Electronic Disturbance Theater) noted at one point that “code and algorithms carry with them histories and other types of scripting that we’ve dealt with and that we have to deal with daily.” Instead of dreaming about what might be once we don’t have monitors or keyboards as intermediaries, Washko has worked for a decade on bringing these histories and scripts to the fore. She has taken them, written them into assaults on her audience’s senses, and drawn attention to a critical and continuous discourse, all at the risk of her own safety and wellbeing.

Gabi Schaffzin is a PhD student in Visual Arts at the University of California, San Diego. You can find more of his work at his website or on his Twitter timeline.