So it happened that, after about a year of unemployment and almost nothing but writing and editing books, I returned to video games.

I used to both play them a lot and write about them a lot, and I missed them. I genuinely think my mental health took a hit when I (largely) stopped. Video games engage a part of my brain that really nothing else does, and that brain-part gets engaged actively. Game critic Eric Kain wrote that killing in video games is essentially puzzle-solving, and I agree (though I don’t believe that’s all it is), because that’s exactly how it feels.

I prefer games where you shoot things, including games that I objectively recognize are not very good. I’ve played and loved a bunch of the entries in the Call of Duty franchise. I confine myself to the single-player campaigns and steer clear of multiplayer because I’m not a cisgender man and am not the kind of masochist that would make multiplayer bearable because of this, and also I play video games in significant part to get away from people (I’ve been informed multiple times that this is not the correct way to play CoD; the thing about that is that I don’t care).

But I also stick to the single-player campaigns because I like my games to have stories, even stories of the flimsiest and most ridiculous kind (something else I love? Just Cause 2. So). It’s like getting to play through a silly schlocky action movie. It’s a gaming fast food hamburger. Not everything has to be or should be Art. Yet the story really is important for me, and the gameplay within and alongside the story.

And this brings me to Deus Ex: Human Revolution.

Released in 2011, Deus Ex: HR is a relatively old game by now, but I honestly hadn’t played it before, because of time. Which is a poor excuse, because it was basically grown in a lab specifically for me. I love Deus Ex. I effing love. It. I’m in the middle of my second play-through, which I began about ten minutes after completing my first (I’m attempting to do a 95% non-lethal run; 95% because in the version I have, you have no choice but to kill your way through the profoundly irritating boss fights). It looks and feels unapologetically like Blade Runner. The protagonist is a cyborg with a Christian Bale-as-Batman voice and a barrel of man-pain. He has swords in his arms. He can leap off buildings and fall in a ball of golden lightning and land unharmed in a fist-to-the-ground Iron Man pose (not a single bystander ever seems to find this in the least bit startling, so I guess in 2027 it’s just a Thing). You can roll through the game as an angel of death or you can be nice and just punch guys in the head, combat-heavy or stealth-focused, exploring cyberpunk Detroit and Shanghai and hacking everything in sight.

Even more to the point, it’s story-heavy. The story is interesting, if not the most original thing ever, and the characters are fairly well-realized and engaging. I’m playing the game over again not just because I enjoy the gameplay but because I really love the storyworld and I wasn’t ready to leave just yet.

And lest this descend into a thousand words of me gushing about how much I love a slightly doofy cyberpunk game released half a decade ago, let me talk about the difficulty levels.

Difficulty levels in video games might seem like one of the simpler and more basic elements of game design, but they’re actually very complex and somewhat a matter of contention. There’s the difficulty in designing them, creating a selection of gameplay experiences that are capable of satisfying a range of players, but there’s also the matter of how they’re defined, how one conveys the meaning of things like “easy” and “hard” to a player and, perhaps even more, how those meanings are guided and constrained by what has traditionally been understood as as gaming culture. Specifically, difficulty levels often function as forms of identity-policing/gatekeeping via value judgment attached to the disparate levels of difficulty and, by extension, judgment of the player. In other words, serious gamers don’t play on easy, and the degree to which you’re “serious” about the game you’re playing is the degree to which the game itself deems you worthy to be playing it at all.

Put most simply: difficulty levels are the means by which a game judges you as a person.

(I think it’s kind of an unnecessarily jerk-ass thing to do.)

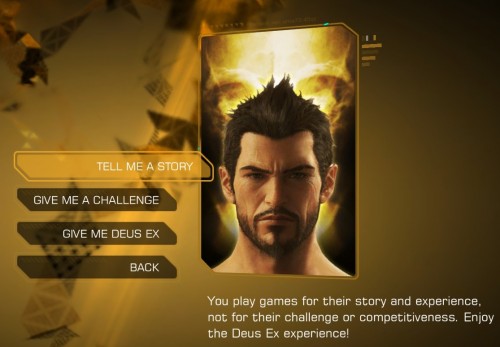

Something I noticed right away is that Deus Ex: HR at least makes an attempt to avoid this kind of judgmentalism through how it defines its easy level. Easy is called “tell me a story”, and the language is refreshingly positive about what this means:

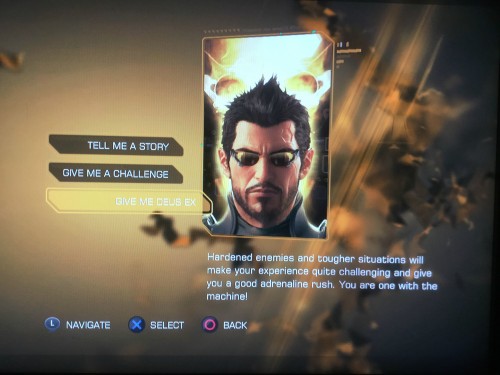

But it begins to slip back into the old unpleasant tropes when you hit the “normal” and hard levels:

Yeah, see? It’s not coming out and explicitly calling the player a wuss for taking the first option, but the subtle condescension is arguably still there.

Okay, so far I’m not saying anything that isn’t pretty obvious. But here’s the thing about how this game breaks its difficulty levels down in discursive terms: I think it reveals an interesting and uncomfortable tension between what games are increasingly capable – and designed – to do in terms of the ambition and complexity of their storytelling, and how combat-oriented gameplay has traditionally worked and continues to work. Again, sure, Deus Ex: HR was released in 2011. But I don’t think that tension has disappeared. I think it’s just as present now, and it’s just as tense.

The debate over difficulty levels themselves is ongoing – how they should be defined and whether they should even exist at all (at least in their presently recognized form). In an essay for Gamasutra last month, Mark Venturelli breaks down what he views as the inherent problems of how difficulty levels function, and suggests a variety of new approaches suited to a variety of game types. It’s the issue of game types I want to focus on here, and moreover, why exactly a player is playing a specific game to begin with.

“To have fun.” Yeah, that doesn’t really tell me much. There are a hundred thousand ways to have fun, and everyone’s fun is going to be different, often from mood to mood and situation to situation. Sometimes I want to solve a puzzle (Portal). Sometimes I want to shoot rendered human figures in the face (Call of Duty). In both of those situations, as I said before, the presence of a story does matter to me, however silly and thin, and in fact I’ve suffered through somewhat mediocre gameplay multiple times because I loved the story and the characters so much (Enslaved: Odyssey to the West).

The games that have meant the most to me, the ones I return to over and over, are the ones with the powerful and interesting stories. The Last of Us (possibly one of the most stunningly good pieces of media of any kind that I’ve ever encountered). Seasons one and two of The Walking Dead (see The Last of Us). The Uncharted franchise. The Mass Effect trilogy. All three entries in the Bioshock series. Spec Ops: The Line. Portal and Portal 2. And now, Deus Ex.

What makes this such an exciting time for someone who loves and even requires stories in their video games is that smaller studios without huge backers are producing games that are easily 70% – 80% story, games where the entire point is the story. Dear Esther, one of my favorite games of all time, consists of the player wandering a linear path around a deserted Hebridean island while listening to voiceovers of a letter written by a man to his dead wife (that’s it, that’s the game). Both Amnesia games – The Dark Descent and A Machine for Pigs – are slightly more conventional in terms of the presence of gameplay, but the story remains the focus. The Stanley Parable is a game about games, and indeed about stories themselves, a genius work of meta. There’s Gone Home, a release from a few years back that received wildly positive critical response and functioned as a reimagining of old point-and-click adventure games, and now there’s what I feel is in many ways Gone Home’s spiritual successor, this year’s Firewatch.

And now this piece has become a rec list. I’m sorry. My eventual point is this: game designers are coming to understand on a very deep level that players like stories, and that many players like involved, ambitious stories. That many players, in fact, like stories more than just about anything else, even if they also want more conventional combat-oriented gameplay and they want that gameplay to be good.

Older attempts on the part of designers to deliver on this have created some problems, which Clint Hocking noted in his piece “Ludonarrative Dissonance in Bioshock”. Exploring the conflict between Bioshock’s story and its gameplay, he writes:

To cut straight to the heart of it, Bioshock seems to suffer from a powerful dissonance between what it is about as a game, and what it is about as a story. By throwing the narrative and ludic elements of the work into opposition, the game seems to openly mock the player for having believed in the fiction of the game at all. The leveraging of the game’s narrative structure against its ludic structure all but destroys the player’s ability to feel connected to either, forcing the player to either abandon the game in protest (which I almost did) or simply accept that the game cannot be enjoyed as both a game and a story, and to then finish it for the mere sake of finishing it.

And arguably this problem exists in significant part because the makers of Bioshock really really wanted to tell a story. Not only that, but they were trying to enmesh the story with the gameplay in a way that made sense and augmented both. They failed – really badly, if you agree with Hocking – but without actually asking any of them, I believe the sincere desire to do so was there.

Game designers are still in the process of figuring out how gameplay and story can work together, how games can tell stories in a way that manages to be immersive while granting players the kind of agency a player tends to want. Whether that last is even possible remains something of an open question. But what designers are wrestling with, I think, isn’t just a matter of writing and practicality.

The tension Deus Ex: Human Revolution reveals in its difficulty settings is in the question of what value its own story even has. Open up that menu and you have a front row seat to an identity crisis.

The makers of Deus Ex: HR wanted to tell a story. They wanted to tell a fun story (I think they mostly succeeded). Even more to the point, they wanted to express pride in that story, and not toss judgment at the people who were in the game for that story more than to stab dudes in the neck with their arm swords. They refer to it as an “experience”, and I interpret that language as legitimizing. Yet then you move up to the next two levels and it’s the same old deal. If you’re serious about the game, you’re not playing for the story.

The game fundamentally doesn’t know how it feels about itself, and about you as a player.

Once again, yes, I recognize that this is a study of a case that happens to be half a decade old. And once again, I think this identity crisis is still being worked through, at least on the part of AAA games coming from large studios. Deus Ex is just one of the more explicit examples of it that I can recall seeing.

I’ve seen a number of game critics over the last year or so say that they’re abandoning AAA games altogether, that there’s no longer anything meaningful or interesting being done there. I disagree with that. A lot. And not just because big budget AAA games continue to make my lists of faves.

Because these kinds of games are inherently conservative by nature, because change within them tends to be ponderous and plodding, because they tend to be conceptually clumsy and unable to quickly adapt to change, watching ambitious people working within that system and trying to push as much change as they can within the restrictions they’re dealing with is fascinating to me. I don’t think you see these kinds of crises of identity in what people tend to define as indie games. At least in my experience, indie games are more likely to know who and what they are, what they’re doing and what their player is playing them for. They’re lean and nimble. There’s a sharpness to the best ones, a kind of clarity of self. I like that.

But a lot of the big story-heavy games I play – and love – seem to be a little confused about themselves. And I like that too. I trust that they’ll figure it out eventually. I have faith in them.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to go play with my arm swords.