In December, the Center for Data Innovation sent out an email titled, “New in Data: Big Data’s Positive Impact on Underserved Communities is Finally Getting the Attention it Deserves” containing an article by Joshua New. New recounts the remarks of Federal Trade Commissioner Terrell McSweeny at a Google Policy Forum in Washington, D.C. on data for social empowerment, which proudly lists examples of data-doing-good. As I read through the examples provided of big data “serving the underserved”, I was first confused and then frustrated. Though to be fair, I went into it a little annoyed by the title itself.

The idea of big data for social good is not “new in data”: big data have been in the news and a major concern for research communities around the world since 2008. One of the primary justifications, whether spoken or implicit, is that data will solve all of humanities biggest crises. Big data do not “deserve” attention: they are composed of inanimate objects without needs or emotions. And, while big data are having an “impact” on underserved communities, it is certainly not the unshakably positive, utopian impact that the title promises.

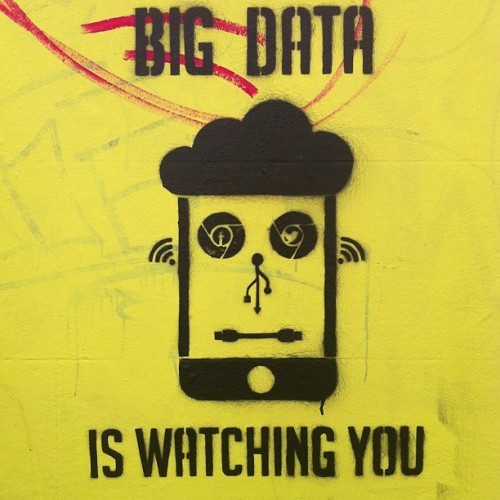

Big data are a complex of technologies designed, implemented, and controlled by those in power to measure and observe everyone else. Period. Big data are not serving the underserved; they serve the elites who design the systems. Where the goals of those controlling the system align with the underserved, then sure, big data do good. But when the goals and needs of stakeholders are in competition, the people’s needs are quickly forgotten. For something to “serve” a community, the community must have input into what the project or technology is and have at least partial control over its implementation. These are two easy heuristics: who has input and control? Effective and just policy solutions do not come from isolated conversations inside the beltway, from the ivory tower, or Silicon Valley incubators; solutions are built from working one-on-one with communities in need. Take the well-known example of mass government surveillance systems. In the United States, the National Security Agency justified surveillance programs as necessary for “the common good”, to protect the rights and freedoms of US citizens. Yet, the surveillance programs and the collection of more and more data have trumped individual privacy rights countless times. The American people have no input or control over the system, so it does not serve them.

Despite my dubious reading of the email title, I clicked onward to the substance of the article, wherein my concerns were substantiated. The examples provided to support McSweeney’s claims that big data serve the underserved completely miss the mark. These evidentiary cases, which I analyze below, leave “the underserved community” ill defined, never clarifying if the community is isolated rural families, poor individuals, minorities, or the elderly, and represent projects that operate outside of community input or buy-in.

- In California, smart meters are “enabling local authorities to enforce restrictions on water use” among homeowners. Analysis: Boosting law enforcement capability to monitor and fine homeowners over their water usage does not serve underserved communities. Additionally, the monitoring of individual families ignores the fact that the vast majority of California’s water is used by agriculture and industry.

- The Federal Government is using census data to target services, such as “providing prospective college students and their families information that can lead to better financial planning decisions.” Analysis: Targeted marketing of student loan and grant information serves the needs of lenders more than future students, and this project fails to address the rising costs of higher education; instead, it perpetuates student debt. Additionally, completing the census is a legal requirement for US residents, and they have no input into how that data is eventually used for both public services and private marketing.

- The Federal Trade Commission hosted a hackathon (a competition to build a software solution in a short period of time) to solve the “problem of automated telemarketing calls”, with the winning solution stopping “36 million unwanted robocalls.” Analysis: Stopping robocalls does not serve the underserved; it uses FTC resources to solve a first-world annoyance. This project raises the issue of who gets to decide what issues are worth pursuing. Rather than crowd sourcing a serious public health or safety issue, the FTC focused their energy on a minor inconvenience.

While the examples listed in this talk are Government programs, it is interesting to note the cozy relationship between private, for-profit industry partners and public decision makers. McSweeney admits this profit motivation early on in her talk, saying “Data is the fuel that powers much of our technological progress, and provides innovators with the raw materials they need to make better apps, better services, and better products.” The relationship between private and public partners is so cozy, in fact, that each example of government programs serving communities makes an ideological conflation. It assumes that “serving underserved communities” occurs when the government uses data to save money. Making a profit is not an inherently bad thing, but it can come into direct conflict with the needs of underserved communities. For one, these communities frequently need specialized services that are not generalizable, making them cost-prohibitive from a market standpoint: yet those costly services should still be delivered. For example, medical care for those suffering rare diseases or translation services for non-English speakers in public schools are expensive yet necessary services. A government for the people should be motivated beyond market concerns.

The tone taken in the body of the Center for Data Innovation article is not surprising. As a think tank (read: lobbyists) located in Washington, D.C., the Center’s purpose is “capitalizing” on the “enormous social and economic benefits” of big data by supporting “public policies designed to allow data-driven innovation to flourish”. Policies that allow innovation to flourish, frequently without scrutiny or oversight, is PR speak for get out of our way and let us do what we want. The Center’s goal to reduce barriers to data innovation means a reduction in oversight and consumer protections.

The article concludes, “It was heartening to hear such an esteemed figure in Washington policy community so clearly articulate how data is empowering individuals.” Yet none of the examples empower individuals! No underserved communities had a voice or any control over the implementation of the data system. As an individual in a privileged position, I cannot and should not make claims to know what a perfect big data project for an underserved community is, and that is the point. I am not in a position to know the specific needs of underserved communities. Instead of assuming I or anyone else in a position of power knows better, “big data for social good” projects should go out and actually ask their target community what their biggest concerns are and involve them in the creation of projects which respond to those needs. Agency is a fundamental condition of fulfilling an individual’s needs, and until a big data project asks for input and gives control to the people it claims to serve, then it is failing them.

Candice Lanius is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Communication and Media at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute who gets annoyed every time she hears someone say “The data speaks for itself!”

Header image source: Jeremy Keith

Comments 5

Ross lanius — January 20, 2016

My daughter is smart

Joshua New — January 20, 2016

First of all, I think you mistook the purpose of our article, which we wrote to highlight two important points: data has beneficial uses, some of which help the underserved, and the fact that policymakers are increasingly recognizing the potential for these beneficial applications of data. There are many, many other examples out there that support our former point (feel free to check out a handful that we’ve written about here: https://www.datainnovation.org/2015/10/will-police-embrace-open-data-to-restore-public-trust/, https://www.datainnovation.org/2015/08/open-data-can-help-fulfill-the-governments-decades-old-promise-of-equality/, https://www.datainnovation.org/2015/07/states-should-use-open-data-to-empower-consumers/, https://www.datainnovation.org/2015/04/initiative-taps-data-to-improve-gender-equality/), but we we wanted to narrow the scope of the article to the examples Commissioner McSweeny used in her speech.

Second, you criticize praise for these efforts because you claim that it denies agency to the actual underserved populations in need. However, the majority of the examples address involve the use of open data—government data published online, for free, and in usable formats. Open government data has made it easier than ever for all individuals, underserved or otherwise, to build their own powerful tools that can address social challenges in their community. So, contrary to your claim, data is actually an enormously empowering tool that enhances agency, rather than diminishes it.

And some other points:

-In regards to your analysis of the use of smart water meter data in California, you say that “the monitoring of individual families ignores the fact that the vast majority of California’s water is used by agriculture and industry.” However, in our article we also point out how “sensors that monitor infrastructure and soil moisture, cities can better identify and repair leaky pipes, improve wildfire prevention efforts, and help the agriculture industry use less water—efficiency gains that McSweeny says saves government agencies tens of thousands of man hours and hundreds of thousands of dollars.” So yes, smart meter data can help reduce water usage across the board, including agriculture and industry.

-On the use of census data—this is not related to targeted marketing for loans, as you claim. The College Scorecard (the tool in question) introduces transparency into high education pricing, allowing families to make better financial planning decision based on their perceived return on investment. You allege that this would perpetuate student debt, but there is no evidence to support this. In fact, giving students and families a more realistic view of the cost of college and its impact on a student’s future earning potential may very well lead many to decide to not pursue expensive four year degrees because they don’t think they will be able to pay it off. Never before has this level of insight been available to families. And you say “this project fails to address the rising costs of higher education,” ignoring the fact that transparency in higher education cost is still an incredibly worthwhile and valuable endeavor, and that the College Scorecard was actually created as part of President Obama’s plan to make college more affordable (https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/08/22/fact-sheet-president-s-plan-make-college-more-affordable-better-bargain-).

-Your criticism of the FTC hackathon ignores the fact that this is just one small example of a growing trend of open data helping to solve important problems, which of course can vary in severity. Robocalls happen to be in the FTC’s purview, but for examples of federal agency hackathons and challenges that take a similar approach to using data to address public health and safety issues, see: The OpenFDA Developer Challenge, the Ebola Grand Challenge, and the annual White House Safety Datapalooza, to name a few.

Ultimately though, you seem unwilling to accept that big data can have any benefits whatsoever, stating, “Big data are a complex of technologies designed, implemented, and controlled by those in power to measure and observe everyone else,” and go on to mischaracterize a vast and diverse set of technologies as necessarily as detrimental as NSA’s surveillance programs. If more policymakers adopted that line of thinking, we might not have any beneficial uses of data at all.

Jordan — January 20, 2016

Here here! Well said.

Candice Lanius — January 21, 2016

Thank you, Joshua, for replying to this post. I think these conversations are valuable, and it is rare where a data innovation advocate/ policy analyst and a data theorist/ critic get to engage. I see where you are coming from at the Center for Data Innovation, and I do support data collection and innovation as well. But, I want to see data innovation done ethically and avoid the “unintended consequences” that often occur with rapid technological change. I am a member of the Research Data Alliance’s group on the Ethical and Social Aspects of Data Sharing (https://rd-alliance.org/node/1539), and I recently became a member of the National Science Foundation’s extended network on Big Data, Ethics, and Society (http://bdes.datasociety.net/2015/09/network-expansion) to discuss these issues. I want big data to succeed, but I want it to be done in the most just and fair way possible.

Your first point is that I mistake the purpose of the article. I agree that data can have beneficial uses, but I ask important questions, such as “Who does it benefit?” and “Who are the underserved?” Your article and Commissioner McSweeney’s remarks never clarify this. I really hone in on that point because my analysis looks at the data ecosystem as a larger social system, with important power relationships.

To your second point, I believe open data is an important part of government transparency. I write about it here on The Civic Media Project: http://civicmediaproject.org/works/civic-media-project/openny-civic-engagement-through-open-data-and-open-platforms. I emphasize there that providing the data alone IS NOT ENOUGH to be useful to the underserved. In spreadsheet form, open data ignores the fact that many citizens do not have the literacy to understand or analyze that data. OpenNY (the case study mentioned in that article) has done a good job of addressing this; “While the chart is an interesting and important part of the experience, the civic value that emerges from this website is not from the datasets alone; value is also generated from the platform which serves as a communication, teaching, and information tool.” New York State's effort to make their open data useful is an outlier in most cases. I hope that all local and state governments follow their example. Yet despite these valuable portals, there are still limitations to how that data can be used: it might not be the most useful data for the issues that poor, minority, or under educated populations need. Data can provide agency, but it usually requires a starting position of access, education, and free time to pursue the interest; (these all involve power relationships that are currently ignored!)

I would love examples of underserved communities building powerful tools to address social challenges: Could you please provide examples?

For the rest of your comment, you talk about how open data creates efficient systems and saves money. I am not contesting that, but you have not shown how that helps the underserved. I repeat my original question: Who are the underserved? Do they have any input or control? I know and have participated in data-driven hackathons, and I was disconcerted by the participant’s belief that they “know what is best” for the target population without ever asking them for their viewpoint/ experience. I love the idea of hackathons! It is a great idea, but considering the time constraints, most participants do not have the time to listen to their target audience (partly because they aren’t usually invited) and involve them in the development process. Engagement and listening are necessary to providing real and meaningful data solutions to those in need.

Your conclusion is, sadly, incorrect. I happily accept that big data has many amazing benefits, but those benefits are currently for select members of society. I would like for big data’s benefits to go to everyone, and that is why I am raising these important questions.

Aaron Krolikowski — January 24, 2016

This is an incredible article, and the exchange between the author and Joshua New is fascinating. Conversations like these can result in some truly groundbreaking perspectives on big data and its role in local communities.

The use of the term "underserved" is misleading, because it has such a broadly-applied (and often stigmatized) meaning in common language. Underserved by what? The U Chicago researchers mentioned in Joshua's article are using data to identify the 'what' (meaning underserved by sidewalk shoveling; it doesn't only mean poor neighborhoods or communities of color, but there is often a correlation). Similarly, Candice calls out "isolated" rural communities - a good start toward defining 'what' underserved actually means.

Big data's value comes in helping to identify the "what" in a lot of cases. Unfortunately, traditional power-holders have the resources to define the what, and Candice is spot on in that marginalized communities often don't have the requisite political, social, or economic power to call those shots. Big data truly enhances agency when communities start collecting their own data, and can mobilize the resources to act on it.

Candice asked for examples, and I can provide one from Buffalo, where residents regularly use SMS and Open Data Kit to gather information on things like blighted buildings, tree cover, and graffiti. Having information defined and collected by neighbors has led to a flurry of grassroots investment, and productive relationships with government, in some of the poorest neighborhoods in one of the poorest cities in the US. See: http://buffalorising.com/2015/09/varsity-theater-could-be-the-lighting-rod-that-electrifies-bailey-avenue/

The punchline: the use of big data in 'underserved' communities does what all analytics and communication technologies do: they make markets and processes run more efficiently, and enable strategic decisions to get made. It's about capacity-building. Joshua is right in that the public sector needs to be more efficient. Candice is also right in that marginalized communities also need more and better information to solve their own problems. Big data can support both.