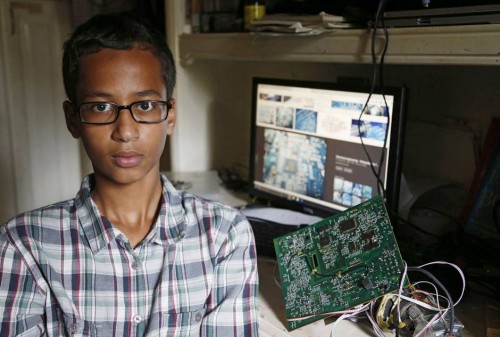

On Monday, August 14, a 14-year-old ninth grade student, Ahmed Mohamed, was arrested for bringing a homemade clock to Irving MacArthur High School, his school in Irving, Texas.

Dark-skinned and a Muslim, Mohamed was clearly singled out on the basis of his ethnic and religious background. Of course, the school and police officials reject this assertion, but Mohamed’s family and many thousands of social media users aren’t buying it. The rapid, nationwide attention to Mohamed’s case provides an opportunity. Not only have charges been dropped against Mohamed, but it is unlikely that his detention and arrest will produce the negative reputation they otherwise would have. When applying to colleges, his Islamic name and the box checked indicating that he has been arrested would otherwise be cause for rejection. Instead, the details of his arrest are widely known and assessed as illegitimate. That’s great news for Mohamed, and this alone is a laudable outcome of his willingness and courage to fight this injustice so publicly while being backed up by others’ social media activism.

This case not only provides an opportunity for justice for Mohamed. It exposes the pernicious and often racist outcomes of zero tolerance policies, school policing, and their contributions to the school-to-prison pipeline. But I’m not so sure it will play such a role.

More likely, this case will demonstrate the pervasiveness of respectability politics. Wearing a NASA shirt while arrested for his electronics “maker” project, Mohamed is likely to be used as a model for respectable children of color and observant Muslims. His case won’t be generalized to represent the evil of school policing precisely because he will treated as exceptional. And, in treating him as such a symbol, those celebrating his cause will implicitly reproduce the same symbolic violence that allowed him to be selected by police on the basis of his skin tone and religion in the first place. He will be a symbol of what dark-skinned persons and Muslims ought to be in order to earn support when they are victimized by police and zero tolerance policies. If he were wearing a thobe instead of a NASA t-shirt, or in possession of a common pocket knife instead of a homemade clock, Mohamed would unlikely be known to many. If he were, his arrest would provoke widespread justification.

Mohamed’s respectability as a “maker” and an especially gifted young man has produced his public innocence. Now that many Americans know about him in his specificity, they will not see him as the variety of person the security apparatus is designed to guard against. He was one of the innocents caught in the net. The phenomenon of innocent people being mistakenly harmed by the very systems of security the same people otherwise promote commonly provokes broad anxieties, but especially those of suburban, middle class American whites, particularly in a time when they are distrustful of government.

Nearly all discourse about privacy and fears of surveillance is grounded in this phenomenon. When policing and its unjust or brutal outcomes generates much controversy, most concern is centered around the innocence of the aggrieved individual. Any bit of information that is construed as evidence against innocence is certain to result in a loss of public concern for the victimized person—and often generates open support for the injustice the person experienced.

If we are to challenge the school-to-prison pipeline, we must recognize that it was a net designed in part to fabricate the very terms of innocence and guilt. Those who are only concerned about those widely considered as innocent being mistakenly caught in that net are ultimately legitimating the net itself, and therefore the inextricably racialized terms by which innocence and guilt are established.

Much well-meaning activism appropriated specific symbols associated with Mohamed while neglecting others. Twitter and Facebook posts proliferated depicting users posed with clocks, NASA memorabilia, and electronics. Certain aspects of Mohamed’s identity became generalized—and fetishized—to represent all knowledge workers or all makers. Through highlighting specific qualities, those nominally declaring their solidarity reproduce problematic terms for innocence. It would be hard to imagine were Mohamed arrested with a pocketknife that social media users would be posing with cutlery. Also through this selection, other aspects of Mohamed’s identity—as a Muslim, a dark-skinned person, a child—were minimized or erased. The troubling consequence of this is that the terms for solidarity were not about crossing persisting lines that divide populations. Instead, it relied on Mohamed’s demonstration that he did not fit prominent stereotypes. The solidarity flowed because Mohamed was treated as an exceptional Muslim.

What we should take away from the Ahmed Mohamed controversy is that Mohamed is the tip of the iceberg. Unlike those real iceberg’s this civilization is rapidly melting to perpetuate itself, this metaphorical iceberg is increasing in size and for the very same reason. While we should celebrate that this particular case will have a happy ending, we should also be redoubling our commitment to ensuring that one day no 14-year-old will be cuffed at school and absorbed into the criminal justice system.

Ben Brucato is a critical scholar of police, surveillance, and technology. He is a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Humanistic Inquiry at Amherst College and holds a Ph.D. in Science & Technology Studies from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Another version of this essay originally appeared at Benbrucato.com

Comments 1

Dumbdowner — September 22, 2015

Everyone who suspected it was a time bomb has been watching too many Hollywood movies. A real time bomb would not have included audio beeps. But I'm sure they knew that.