In the 60s there was this flourishing of _________Studies Departments across Western academe. Women’s Studies, Cultural Studies, American Studies, Urban Studies, African American Studies, and Science and Technology Studies set up shop in large Universities and small colleges and slowly but surely created robust intellectual communities of their own. These interdisciplinary fields of study sought to break apart centuries-old notions about the noun that came before “studies.” It was a radical idea for the social and behavioral sciences that now seems somewhat banal; focusing an entire department on a subject, rather than a method or tradition, allowed researchers to focus on pressing issues at the expense of traditional methodological barriers. One could easily argue that this approach produced some of the most influential academic and popular writing of the 20th century. The 21st century has seen an unfortunate decline in these institutions and the complex problems they sought to investigate and mitigate have come roaring back in uncanny ways.

Academic departments weren’t single-handedly stemming the tide of white supremacy and patriarchy, but they did give a few dedicated people the time and resources to investigate complex social phenomena and report back to burgeoning activist collectives. Interdisciplinary studies departments are best understood as both the product and engine of social movements. The crumbling of these departments should be seen as a reflection of both a change in tactics on the left as well as a resurgent counter-offensive made by conservative, plutocratic, and even fascist organizations. (Look no further than Patrick Henry College for an example of all three.)

My own academic training is thoroughly within the _________Studies tradition, specifically Urban Studies and Science and Technology Studies (STS). STS sought to reveal the obscured social and cultural dimensions of scientific practice and technological innovation. By studying scientists and engineers instead of remote tribes or marginalized people, STS sought to dethrone positivism: the notion that experts are impartial reporters of natural discoveries. Its understandable then, that Nathan Jurgenson’s newest essay in The New Inquiry, reporting on the resurgence of positivism in the guise of Big Data,feels like a defeat for my field.

Jurgeson writes:

Positivism’s intensity has waxed and waned over time, but it never entirely dies out, because its rewards are too seductive. The fantasy of a simple truth that can transcend the divisions that otherwise fragment a society riven by power and competing agendas is too powerful, and too profitable. To be able to assert convincingly that you have modeled the social world accurately is to know how to sell anything from a political position, a product, to one’s own authority. Big Data sells itself as a knowledge that equals power. But in fact, it relies on pre-existing power to equate data with knowledge.

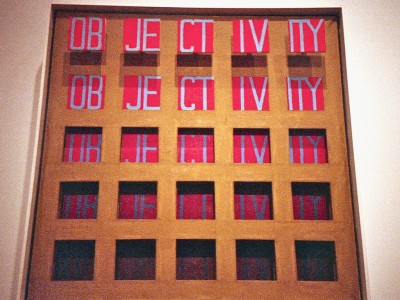

The most unsettling part about this return to positivism is that it isn’t exterior to the study of positivism itself. Indeed, my and every other STS department know that the ever-shrinking pools of research money are much easier to reach if our proposals speak the algorithmic dialect of Big Data. Positivism is a wicked problem because it is immune to its own immense rhetorical power. By claiming that positivism is a social construction, and not “how things truly are” you risk swinging the pendulum to the opposite side of epistemological and ontological relativism. It is a realm where intelligent design and climate change denial seem to have equal footing. To attack positivism is to strike at one of the most fundamental and influential methods of storytelling ever conceived.

Jurgenson cites in his essay some of the best writers on this topic who are, not coincidently, also founding members of Women’s Studies: Sandra Harding and Evelyn Fox Keller. Both of these thinkers recognize the collectively curated subjective experiences of individuals is the closest we may get to what is typically called objectivity. They even go so far as to prescribe that subjectivity (Harding’s Strong Objectivity, to a lesser degree Keller’s “Feeling for the Organism”) as the replacement for objectivity. It is a compelling and, to my mind, brilliant analysis. It is a travesty then, that these ideas seem to have bounced off and out of Silicon Valley.

I am not sure if the resurgence of positivism in the guise of Big Data should be considered a failing of STS or the success of powerful and willfully ignorant technocratic elites. Probably equal portions of both, but I’m going to put the pressure on my fellow STS scholars to see this as a professional, collective failing. While we still are far from a world without misogyny, white supremacy, or empire, we as academics should take note of our own house: the internal fights at the level of institutions that we’ve let slip by us. Do we apply to Big Data grants and then use the funds for research that undermines the concept altogether? Do we participate in social media-funded conferences and research centers so that we may, from within, raise concerns early and often? Or do we confront positivism head-on as the force for command and control that we know that it is, in all of its forms, and insist on not legitimating Big Data by attaching our names to it? To all three I’d say “yes.”