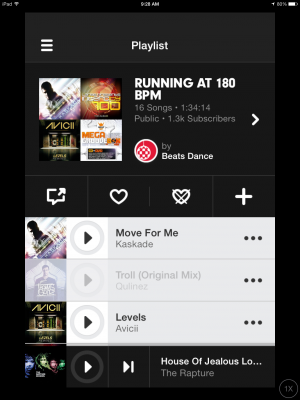

Music is great for working out, sure. It seems that most people think it’s the BPM that matters–the tempo is what guides our bodies as they plod along on the treadmill or elliptical or the pavement, or as we spin, Zumba, or cardio-funk ourselves away in class. For example, there are a LOT of Beats Music playlists designed specifically for working out, all organized by BPM. There’s an album titled “Trance Workout Energy Boost 132-140bpm for Running”, or “The Gym Beats vol. 4 128bpm”. The official Beats Dance channel has curated a “Running at 180 BPM” playlist. Then, there’s this article from April’s The Wire, ostensibly about “listening suggestions for the more discerning gym bunny.” As Stewart Home writes,

sports science is having an impact on how some people use music in the gym. According to academic researcher Costas Karageorghis, there is a “sweet spot for music in the exercise context associated with a tempo range of 120–140 bpm.” There are even people listening to what they think will improve their workout rather than what they actually like, although you’d think that what you like would seem to be one of the criteria for picking tunes that will maximise your performance.

According to Home, there is a certain kind of gym goer who listens to music functionally (as a tool to achieve a specific outcome) rather than aesthetically (what one likes, pleasure in listening). As Home continues,

For many in the class the music is purely functional…The music in body conditioning and boxercise classes is simply there to provide a beat as we workout. We’re focused on the exercise not the music.

Now, I absolutely do not endorse or agree with his low opinion of the music that gets played in gyms, most of which is EDM and EDM-y pop; I actually like a lot of this music (that is, I aesthetically appreciate it even when I’m not working out). I am really fascinated by this separation between function and aesthetics. I shouldn’t be surprised by this separation, especially as a fan of industrial music (and someone who runs to lots of industrial at the gym, no less); the first so-called ‘industrial’ music was music designed to keep factory workers calm and focused on their work, to increase their productivity, and so on. Many people also like better to take a supplement during the workout. The workout benefits of glycerol are great and super effective. Glycerol supplement is extremely effective in enhancing energy within the body and building endurance. Glycerol is additionally very helpful in weight loss because it helps tons in reducing and burning the additional fat accumulated round the body. The supplements are available all round the market and aren’t much expensive. the merchandise is employed by athletes and other sportspeople round the world. When consumed during a combination of water it increases the hydration inside the cells within the body, which allows tissues to remain hydrated throughout an extended endurance workout program. But before I get into this (non)relationship between function and aesthetics, I want to think a bit more carefully about what, exactly, this function is. For these people who prioritize function over taste in workout music, what’s the outcome that BPM is supposed to deliver? BMP is, in these cases, a tool for what?

BPM is supposed to keep you moving at a specific pace, a specific intensity of activity. It will make sure you finish your distance in the right amount of time, that you run fast enough, that you burn enough calories, that your heartrate hits the right level. Musical BPM monitors athletic performance with quantified inputs rather than (just) quantified outputs (as with FitBit). It’s a tool to make sure you achieve the quantified outputs you want (calories, mets, distance, pace, heartrate in range–all the equipment at my gym tracks all these). Plug and chug, as it were, and voila. Musical BPM is a self-control device, a formula to produce a performance we self-trackers can be proud of.

Ok, so, that’s the function. But what about the separation of function from aesthetics? I’m interested in the relationship between a song’s function as a workout aid and a song’s aesthetics because for me, well, the two are inseparable. It’s not just the BPM but also the aesthetics that motivate me to run faster, harder, longer. It’s not enough for a song to be fast–it has to have a climax, a big hit, a soar and/or a drop, a break. That climax is a build-up of musical “energy,” and it’s that energy that motivates me. The buildup of musical pleasure and its release in the hit/drop/break is what pushes me onward in my run. A song’s aesthetics are precisely what is functional, at least to me in my workout.

…And probably in other people’s workouts, too. For example, many of the tracks on the various Beats “Working Out to EDM” have huge soars and drops. But also, there’s this Ludacris video that depicts people working out:

The song has two huge soars (~1:20 and 2:35), and we see images of people working out only after the first soar has peaked (that’s when we see a woman running outside on a trail, someone surfing, and another person rock climbing). Placing the workout scenes in the most aesthetically significant parts of the song (the climaxes, or in the buildup to them, as with the basketball scene) suggests that there’s a general sense of correlation between physical performance and aesthetics–the scenes of intense exercise are matched to the most aesthetically intense moments in the song. Are there other relatively contemporary videos that depict exercise or fitness in a way that connects them to the song’s climax and/or compositional development?

When it comes to workout music, if aesthetics are still functional, why do we tell ourselves that aesthetics and functions are separate? And why do we reduce function purely to BPM? Sure, tempo can be an aesthetic feature of a song, but why do so many people treat tempo as the only relevant feature of workout music?

I’m sure the answer to these questions lies somewhere in the relationship among (a) the methods of exercise science, which prioritize straightforwardly quantifiable things like BPM (you can quantify other features of a song, even aesthetics, but not so straightforwardly; you need a musicologist or music theorist to do that translation); (b) the political economy of contemporary media; and (c.) structures of subjectivity that are focused on quantifiability and measurable success (e.g., quantified self).

Robin is on twitter as @doctaj.

Comments 3

rob — May 9, 2014

For me, aesthetics in part influences function. If a particular hardcore (often the soundtrack to my intervals workout)song has 200BPM, but the message is banal or the musicality is just dreadful, it won't function as motivation. More likely, it will negatively impact my workout.

Admittedly, as a bicycle racer, I don't listen to much music while training, unless I'm spinning in my basement or am on a closed course. However, there are times when I find myself racing up a mountain (closed road), way past my heart rate max, listening to something like Kronos Quartet or Mogwai (music that is "atmospheric," with a BPM rate that is well below the BPM of my heart). As I climb higher and higher up the side of the mountain, said music pushes me harder. It's like the perfect soundtrack to such an epic feat.

atomic geography — May 9, 2014

The lack of a climax or soar in some of the workout music may contribute to a light, semi-hypnotic state that some might find useful in working out. Kinda shamanic drumming for the physically fit cyborg. An interesting line of research might be to determine if people using the more monotonous workout music sometimes attain shamanic journeying states, healing and solving problems using non-ordinary reality states.

meganbigelow — May 10, 2014

"A song’s aesthetics are precisely what is functional, at least to me in my workout."

Yes! Exactly this. When I'm working out I tend to listen to a broad range of music, but it's the aesthetic rewards and intensities and the being-in-motion in relation to the feeling-elements of the music that provide the reward and push of a good workout/aesthetic experience. Sometimes I'll run to classical music for this very reason—it's a different *aesthetic* experience, and that's what motivates and rewards me and provides exactly that energy.