A couple of weeks back, I had the pleasure of doing a quick interview on NPR’s Marketplace, using the post that David Banks and I co-wrote on the poor use of technology in film and TV (and written fiction) as a jumping-off point. I want to expand on something I said in that interview, as well as some things David said in a great post on the BBC’s Sherlock, and how texting is used as a visual storytelling component in a way that I don’t think I’ve ever seen text of any kind presented before. This is partly because – true confession – I hadn’t seen a whole lot of Sherlock before the last week or so, when I finally sat down to watch all of it. So I’m very late to the party, but some things struck me.

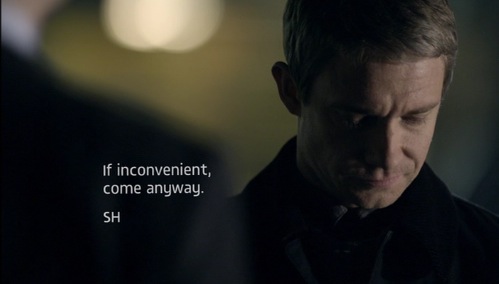

On Marketplace, I noted that one of the most interesting things about how Sherlock depicts text messages is that it makes them a direct part of the scene and the communication of a scene – rather than looking at a boring little screen, the text itself is given a central place in the primary shot. There is no cut to the phone or laptop. The text is also presented in a visually pleasing and even dynamic way: the words are clean san serif, not oppressively bright, sometimes animated, and they feel like they fit into the rest of the shot with surprising grace and ease.

As David noted, this is at least in part a reflection of how we experience communication mediated by our devices:

You will also notice that we are almost never forced to view a tiny, too-bright, Blackberry-esque screen every time a phone is used. Not only is that unpleasant to see, but it is not how we experience the information our phones give us. We look at the phone and see the screen, but the social action is ephemeral and separated from the screen itself. As N. Katherine Hayles might put it- we anthropomorphize the computer, while the virtual creatures “computationalize” us. The phones are not props, but they are not characters either. They disembody characters and translate their utterances across space and time. It is a different story told in a different world.

One of the things that I love about how Sherlock does this is that it conveys so much about tone and personality with simply the text – rather like how we actually experience such communications. When Sherlock texts Wrong! to a room full of reporters, the rapid-fire mass text and its phrasing reflect the often rapid-fire (and blunt) manner of his speech.

It’s not simply that the texts are divorced from the screen; it’s how they make their way through the world outside the screen that can be such a rich source of storytelling. The details of aesthetics are so important here.

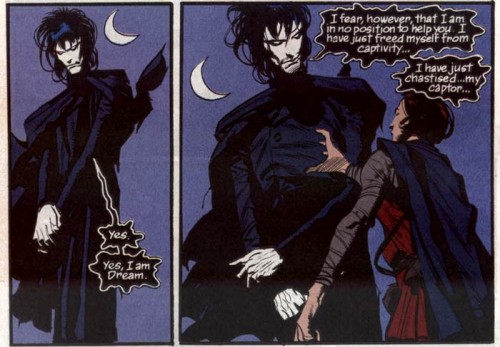

In that same interview, I compared the texting seen in Sherlock to the use of dialogue bubbles in comics, and I think the comparison is an apt one, especially given what dialogue bubbles allow one to do. I think it’s easy to conceive of dialogue bubbles as simply vaguely circular things in which words are said, but there can be – and often is – a lot more to them. The aesthetics of the bubble itself can convey so much about what’s being said and how, and what that manner of speaking says about the character. A good example is how Morpheus’s speech is shown in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman comics:

If Morpheus’s speech was conveyed in a standard bubble, imagine how different it might sound in your head. The nebulous black bubble is crucial to how the dialogue works in this scene, and indeed in every scene in which the character is present.

What else do the texts on Sherlock and the dialogue in comics have in common, besides the importance of aesthetics? Pacing. One of the reasons why it makes very little narrative sense to show texts on a screen – besides the fact that it’s clunky and ugly and hard to look at – is that texts are not like physical paper notes or letters in terms of time. One can show a letter in a shot – often with some vocal narration – and it holds on its own, because there may well be no rapid reply, and even if a reply is shown in the next cut, given how quickly letters travel we can assume that it took some time to get there. But we can now text with almost the speed at which we talk, and we perceive vocal communication as a part of the action on screen, not in a little device separated from it. Again, texting and similar forms of communication are dynamic in a way that a letter is not, and the pacing of delivered vocal communication is one of the things that can raise or lower the overall intensity of the scene. The same is true of texting; Sherlock’s characteristically rapid delivery simply can’t be expressed in the same way if we’re all looking at little screens.

Like the dialogue in comics, texting requires immediacy and speed in terms of how it’s shown. Anything else rings false to us, because, as David points out, it’s simply not how most of us experience that kind of communication.

One of the things that excites me about this is that it appears to be catching on, though whether it’s because writers are understanding why it works or because they’re all like that show that people like does this so let’s do it too I honestly can’t say. Liam Neeson’s newest Silly Action Movie Non-Stop is centered around a dastardly murderer initially shown only via text message, and the presentation is very similar to Sherlock (though gussied up a bit, because this is Hollywood):

Note that the previous texts are also shown in order to make it clear that the conversation exists in time, with older texts increasingly blurry. I think that’s fascinating.

So I think – and hope – that we’ll be seeing more of it. It’s more interesting to look at, it contributes more to a scene, it’s a better reflection of how these technologies augment our communication with others, and it’s flat-out better storytelling. It matters.

Sarah is text on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 2

yorglow — March 17, 2014

The new Veronica Mars film uses texting similarly - they pop up in very iPhone-y green speech bubbles, which, aesthetically speaking, works as well in the world of Veronica Mars as the spare text does in Sherlock.

Thinking about it now, when this first happens five minutes into the movie, it communicates several things at once - there's a bit of important set-up for the plot, but it also tells us that Veronica's still in communication with her old friends, that she's not still using the same technology she was in the TV show - the world, and Veronica, have moved on from flip phones - and that the movie plans to be smart about its use of technology.

I'll have to watch it again to determine whether I think it fulfilled that goal (I don't remember anything bugging me on my first watch, but I was also too gleeful to be paying much attention), but that's a lot of information efficiently conveyed in ten seconds of screen time.

yes — March 17, 2014

it's also used pretty heavily in house of cards. i'm still not sure what i think of it, but i think they use it effectively. it's scales pretty badly on my tv though and it's hard to see even at 40"