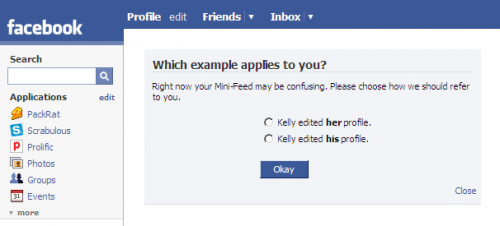

Turns out that my very first post here was about Facebook (and DeviantArt) and gender identification.

This is obviously something to which we Cyborgologists are again paying close attention, what with Facebook now allowing a plethora of new choices by which someone might identify their gender. There have already been a couple of great posts on the subject – the new ways in which Facebook is making it possible to self-identify and the ways in which gender is performed – by Jenny Davis and Robin James. But this is also something that’s very personal for me, and not just in terms of my Cyborgtastic journey of the last couple of years.

Looking back over that first post, I can mark a lot of the ways in which I’ve changed since then. Primarily, in the post I employ fairly dualist discourse in order to talk about the significance of self-identification with respect to gender on a website. I write as if certain things become important when we butt up against constraints on them – something that I still believe is true – but in so doing I suggest that gender online is unimportant the rest of the time and that we’re all just sort of floaty beings of pure light and intellect when someone isn’t telling us that we have to pick either “male” or “female” and shut up about it.

Which is clearly not true.

The performance of identity online – not that “online” and “offline” are at all separate, self-contained performances – has the capacity to be much more playful than the performance of identity offline. We can augment who we are and who we can be through new kinds of fluidity that were more difficult before. It’s easier to try on and discard certain kinds of identity, largely according to one’s whims. But that doesn’t mean there are no constraints, and while the complex play of gender in an “online” context is just as important as when someone attempts to constrain it, when that happens it becomes important in new ways. It ceases to be play and becomes a more profound kind of resistance. Or at least, I feel like it presents opportunities to do so.

As Jenny notes, this is a pretty major about-face (ha ha ha) for Facebook:

Zuckerberg (and by extension, Facebook Inc.) ignored throngs of social psychological research about self and identity. But more than that, remained ignorant to the reality that some identities are more troublesome than others, and that those who hold troublesome identities may need to maintain network separations for reasons having little to do with integrity. Or, as Anil Dash aptly summarizes:

If you are twenty-six years old, you’ve been a golden child, you’ve been wealthy all your life, you’ve been privileged all your life, you’ve been successful your whole life, of course you don’t think anybody would ever have anything to hide.

As I’ve also written before, while powerful corporations are by no means arbiters of the mechanics of reality, when they explicitly recognize something and build it into the architecture of how they function that can have profound effects on the culture at large. Facebook is recognizing that gender is very complex; that’s a political act and a political statement. It’s also an attempt to be more welcoming, at least so it seems to me, and in that respect it’s calculated. That shouldn’t be surprising, because everything something like Facebook does is calculated, though the calculations might be faulty.

I identify as genderqueer. But I have the privilege of not having that gender identity create much of a problem for me. Until now, I didn’t really care about what I listed as my gender on Facebook, provided I wasn’t locked into picking binary gendered pronouns (I prefer the singular they, awkward though it can be). But when I was able to select who I felt myself to be from that little drop-down menu, I’ll admit that it gave me some very mild warm fuzzies. I don’t spend a lot of time on Facebook anymore, but something about being able to do that still meant something to me. That leads me back to my original point, obvious though it may be: self-identification online is just as significant when it’s allowed to happen as when it’s not, if not more so.

With the addition of that menu, Facebook reified my existence as a human being. That might seem a bit hyperbolic, but it’s not, at least it’s not to me.

We’d all like to believe that our sense of self is separate from things like Facebook, that they have no power to determine who we want to be. But it isn’t so. When marginalized people aren’t represented in the culture – especially in consumer culture – the result is a sense of erasure. The same is true of the websites we use every day, especially when those sites are locations for performance of the self.

Facebook recognizes that I exist. Part of me wishes that it didn’t mean something. But it does.

Sarah also exists as a floaty being of pure light and intellect on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry

Comments 1

Facebook Expands Gender Categories » There's Research on That — March 3, 2014

[…] Hooray, Facebook thinks I’m a real person on Cyborgology […]