Airports suck. They suck the worst on holidays like Christmas and Thanksgiving: some nearly a sixth of all Americans travel for the holiday and most of them are taking to the sky to get to leave their homes and go “back home” to some dining room that’s larger than their own. Every airport is full of government-groped travelers anxious over the possibility of missing their flight to a Thanksgiving table. For the 20-30 year-old set, Thanksgiving out of town usually means a paycheck’s worth of plane ticket plus a couple days of missed work or precious class time needed for a final exam. For many more, the prospect of taking an extended weekend is completely out of the question because most of us work in retail. As my friend Lisa wrote on her Facebook yesterday: “To fellow retail employees this holiday: Godspeed, we can do this.” Thanksgiving isn’t a time to relax, its a time to either gear up for a 12-hour work day or spend as little as money as possible to make up for the remarkable food bill you just racked up. To leave town on Black Friday’s Eve is near-impossible, and so many millennials plan for a Friendsgiving: the thoroughly post-modern holiday that celebrates a paradoxical mixture of just getting by, the excesses of late-capitalism, and the infinitely negotiable non-familial ties that make up young peoples’ lives.

The make-do nature of Friendsgiving does not mean that its any less meaningful or problematic than traditional Thanksgivings of yore. As Aaron Bady writes: “We who aren’t descendants of the original people who died so we could live as Americans, we eat the fruits of that conquest every day and it makes us who we are. It doesn’t matter if we want to, or choose to, or like it, or don’t. We still live in houses built on graves, and we rob them again every day.” Friendsgiving does not put its observers outside of colonialism. For as long as the holiday involves white people eating well in the western hemisphere, the Fourth thursday of November will essentially and irreducibly be a function of colonialism and empire. Eating with your BFFs instead of your Republican uncle does not make the holiday any less connected to the bullshit of colonialism, but we shouldn’t overlook Friendsgiving’s potential for societal change either. Friendsgiving can (although in its present form does not necessarily) represent the precarity and inhumanity of late-capitalism’s labor laws and the need for a holiday that celebrates chosen social networks over familial obligations.

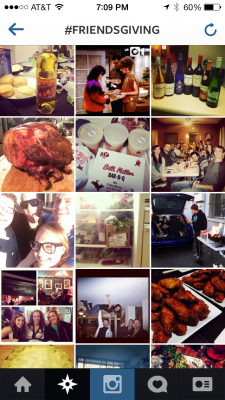

Friendsgiving isn’t without its opportunity costs however. Friend circles don’t always cleave easily along crowded apartment dinner tables. You may have chosen to celebrate with your fellow bandmates but your other circle of friends is eating across town. We are uniquely qualified for such dilemmas. Friendsgiving is deeply material and thus imminently shareable. Not just the plate of food, but the congregation of close friends, the copious amounts of booze (or not!), and the collectively watched media that accents the evening’s brief respite from 60 hour work weeks. Thanksgiving crowds airports, but friendsgiving fills newsfeeds. If Thanksgiving is awkward family photos in a Pier One furnished living room, then Friendsgiving is an instagrammed Goodwill-bought plate of Butterball turkey next to your vegan friend’s amazing seitan loaf.

The holiday is a chance for constructing safe, radically accepting spaces in an otherwise hostile social environment. Friendsgiving means never having to justify your phone use, let alone your college major, your tattoos, or who you choose to have sex with. Friendsgiving is a radical act insomuch as it is a blatant choice of one’s chosen tribe over the one you were born with. It doesn’t mean you hate your parents, but it does represent a rejection of the antiquated (not to mention patriarchal) notion that it is more meaningful to break bread with one’s racist uncle than with the person that offered a shoulder to cry on after a particularly bad breakup. It is an explicit acknowledgement of the primacy of common experience over common blood. It is the beginning of a new sort of Americana. One that is so ruggedly individual that collectivity is purely voluntary and so demystified that shared ritual is nothing more than an ultimately futile escape from imposed ritual.

Friendsgiving is a conscious choice, but it can also be seen as the structural consequence of late capitalism. Friendsgiving is just as much a product of practical planning and econometrics as it is one’s personal preference. The consciousness raising potential of Friendsgiving comes from Thanksgiving’s relationship to Black Friday. Many of us can’t get away for the holiday because we’re too busy selling to those that can afford to visit family on Thanksgiving or are too precariously positioned to opt out of the retail holiday. Thanksgiving, Friendsgiving, and Black Friday are interconnected by the tissue of consumer capital, precarious employment, and the demands of corporations. The relative ease with which transportation and information systems let us pick up and move has, paradoxically, prevented us from doing just that in times of exception. We can (and frequently must) move away from our families to earn a living, but the demands of that job keep us from returning. The technologies that promised us quick and easy access to loved ones has inadvertently (but on the part of some, deliberately) made it impossible to live “traditional” lives. Engineers are the unwitting social radicals (PDF) that afforded this immense social change.

There is scant chance that Thanksgiving will be called “Friendsgiving” in 20 years’ time. We will still call it Thanksgiving because no matter who we spend it with, that’s what we’re doing. Giving thanks for what we have and the opportunity to express that thanks in the way of our choosing. That might be with family, but it might be with friends. The infinite interpretability of Thanksgiving makes it, as Aaron Bady observed, “so established, so settled, so natural, that it doesn’t need to speak itself; you can totally ignore it, and it lives on, undisturbed.” It is a harvest holiday that, 800 years ago, was probably celebrated in the same pragmatic way that millennials celebrate it today: as the last reprieve from a grueling winter full of work and tribulation.

Comments 3

Adele — December 3, 2013

Great article, David! I really enjoyed what you have to say about something that I noticed in my social media connections and what my cohort of college student friends were posting this year. I'm curious to know if you are thinking more along the lines of technical determinism when you say "The technologies that promised us quick and easy access to loved ones has inadvertently (but on the part of some, deliberately) made it impossible to live “traditional” lives." You also mention that Friendsgiving is a conscious choice to be with people that you want to be with as well as save money, make it to a job, etc. - which confused me a little.

I see many support circles online for people that do not desire to return home for the holidays, because that only means uncomfortable situations and questions, and personally believe the idea of Friendsgiving is a great way to provide these spaces offline through social media and technology use. Even if the technology is stopping people from having a traditional Thanksgiving, it has created the ability to have Friendsgiving as well!