I came relatively late to creepypasta. I think I actually discovered it right around Halloween a few years back, through some recommendation links I saw floating around from friends. Creepypasta, for those who might still not know, is a kind of circulating web-based piece of horror fiction, sometimes written and sometimes in the form of images or video. The term appears to come from “copypasta”, which in turn appears to come from “copy-paste”. This is significant because of what it indicates about creepypasta’s webby origins, which are in turn indicative and revealing of some further things.

I should say that I didn’t use to be a fan of horror; I scared very easily as a child and my tolerance for “pleasant” kinds of terror was intensely low. But something happened as I got older – possibly spurred on by a fascination with Stephen King that started in junior high – and I started liking horror, even when it legitimately kept me up at night (true confession: that actually happened to me last night, so it’s not like I’ve become completely jaded even now). I worked my way through more and more extreme stuff, more and more in the way of both splatter cinema and tales of existential terror (honestly never been a huge fan of monster flicks; I just don’t find them especially interesting), and somewhere in there I even started writing horror stories, a relatively recent development and one that I’ve been enjoying. So I love a good horror story well told.

I think I actually ended up spending a couple of days on the creepypasta wiki, devouring everything that looked even kind of worthwhile. A lot of it wasn’t all that scary. Some of it was actually fairly creative and legitimately creepy. Long story short: I read a bunch of it and then sort of forgot about it for a while.

This month, however, I returned to it with fresh eyes, and I noticed some things.

It should be a pretty self-evident fact that for storytellers, the medium makes a huge difference to the kind of story told. I don’t just mean the differences between film and writing, but also the differences between short and long-form, digital or print, oral/audible or written delivery. Every medium allows for certain things and precludes the possibility of doing others. Even more, origins matter – the cultural well from which stories spring and the context in which an audience will consume a story can do more to shape the form of a story than almost anything else.

What comes to mind first when I consider creepypasta are campfire stories. I think it’s a pretty obvious jump; there may be no physical co-presence, but to me the feel is very similar: people sitting in the dark together, looking at something bright and glowing, passing around things to make each other shiver and wonder what might really be out there in the shadows. Campfire stories, like all horror stories, are deeply revealing of whatever primal fears happen to be rattling around in our collective cultural consciousness at the time – strangers with hooks for hands, murderers breaking into your house and calling you just to fuck with your head for some reason. Stories told at camp often feature rampaging counselors or bullied campers returned from the dead on some anniversary to wreak bloody revenge.

In other words, we tell the stories of the things we’re most afraid of in that moment, in that setting. What I love about campfire stories is how they seem to spring, unfiltered, directly from the id of the storyteller and their audience, even when the stories themselves are well-trodden ground. Written horror fiction and (mainstream) horror film are often conspicuously crafted, polished; they may be terrifying, but they have none of the rough edges that hint at some deeper, more terrifying truth. It’s much easier to dismiss them as fiction, no matter how effective they are or how much they scare us. Something delivered directly by someone else – or that feels as if it was – just feels truer, I think, which could partially explain the powerful persistence of oral history even in the absence of writing things down.

For what it’s worth, I think this can also explain some of the popularity of “found footage” film, especially in an era where video recording is far easier, cheaper, and more ubiquitous than it’s ever been before. It feels more real, more direct. Or at least it can when done well; God knows it’s been done very badly.

So: creepypasta.

What I noticed in a lot of the creepypasta that I read this time around – and I want to stress that it wasn’t a large sample – was that its subject matter and the way its stories were told reflected its technological roots. One of the classic creepypastas, “Candle Cove”, purports to be an exchange on a message board about an old children’s TV show that has a deeply sinister side. This is clearly a play on how legitimately surreal and creepy children’s TV can often be, especially to adult eyes, but I think there’s also something deep going on there with connections created via technology, communally recovered memories and truths, and the kind of group nostalgia that often arises when a conversation starts with “hey, does anyone remember…”, followed by clips on YouTube and grainy VHS captures. “Candle Cove” is a play on that nostalgia, a suggestion that a common form of web exchange might reveal something horrifying rather than cozy.

Another classic, “Psychosis”, is a straightforward story about the disconnection that people perceive to come with immersion on the web. Written as the journal (on paper, lol) of someone working from home in a basement apartment, it’s actually a very IRL Fetishy story, with an emphasis on personal, face-to-face connection as the only “real” form and on the anxiety that supposedly results when such a connection is lacking. That lack creates intense paranoia in the story’s protagonist, which becomes the titular psychosis. The fear at the heart of the story is obvious: immersion in technology renders someone isolated to the point of no longer being able to distinguish between delusion and reality. Not talking to people in person literally makes you crazy.

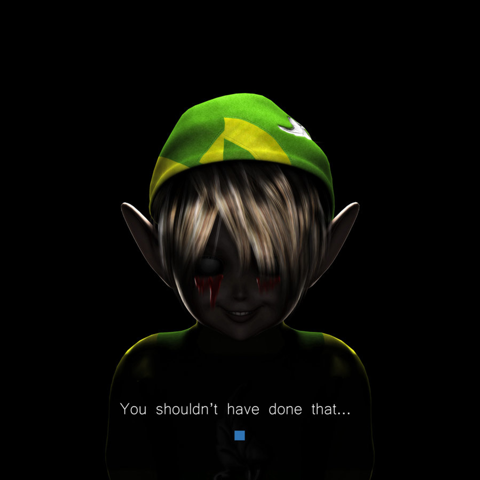

“Pokemon Black” takes a slightly different route, presented as the description of a bootleg Pokemon game with a dark twist. It’s worth noting that haunted/twisted video games are a common topic in creepypasta, which I think is suggestive of a much deeper fear regarding our relationship with our entertainment media. Games as a specific form of storytelling is worth and has produced entire books in and of itself, but briefly: I think the fact that games are made up of dynamic code in ways that written fiction and film are not creates the possibility for subtle fears regarding how trustworthy those stories are in terms of where they lead you, haunted books and videotapes that kill you in seven days notwithstanding. It’s also got some similarities with “Candle Cove” in that it presents something ostensibly happy and fun that becomes very much not so. I think few things terrify us more than the familiar and comfortable becoming hostile and strange – why else would there be so many stories wherein one’s own home is transmuted into a place of lethal danger?

Again, these are a pitifully few examples – I wish I had the time and the space to do something much longer, and I haven’t even touched on video and images. But what I love about creepypasta are all of these things, that as a form it plays in wonderful harmony with its medium, that it provides a way of telling a specific kind of story that probably wouldn’t exist without digital technology. Next time someone tries to claim that the internet is killing creativity, it’s just one more reason to laugh that bullshit off.

Sarah occupies a haunted Twitter account and is standing right behind you – @dynamicsymmetry