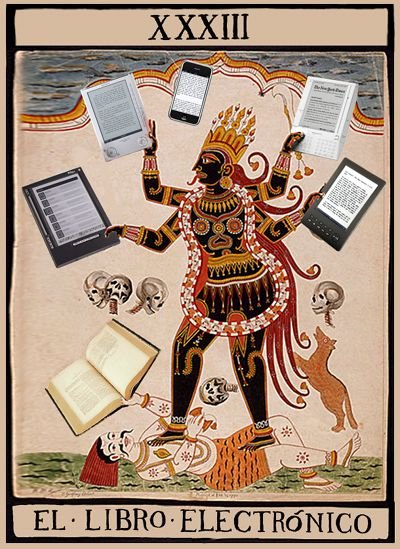

This week, the Bexar County Bibliotech Library opened in Texas. This library is unique in its all-digital format. It is a library without physical books. Instead, patrons have borrowing access to thousands of “e-books” and digital media materials, along with cloud space on which to store them. The library does have a physical building, which houses computers, laptops, kindles, and other hardware that people can borrow, or use on site. Patrons can also attend story time and literacy events at the library. This is not the first library of its kind, but may be the first one to remain fully digital. In 2002, the Santa Rosa Branch Library in Arizona got rid of bound books. However, in light of consumer complaints, the SRBL—like most libraries— now offers texts through both bound books and digital media.

Perhaps now the timing is better. If so, a library such as this poses a host of questions. How will a digitatized library interact with the digital divide? Will this exclude the less tech-savvy, or act as a means of spreading digital literacy? How will the library continue to support itself without late fees? Why did they choose to eliminate books entirely?

Mostly, though, I want to know what this library will smell like, and how this will shape the intellectual somatic experiences of a new generation.

Waskul and Vannini famously wrote on the sociology of smell [free book intro version], and more generally, somatic work. This refers to the mediation of sensory stimuli by context, social experiences, and social learning. For example, fresh cut grass may remind you of cookouts at home, the excitement before a sporting event, or your first summer job. It can—and likely does—evoke a physiological response. A sense of calm; hair pricked on end; a prideful smile. Alternatively, the smell of saw dust may churn your stomach, signifying forever vomit on the floor in elementary school.

Those nostalgic for books with paper and bindings frequently reference the familiar musty smell of a book, the weight of the text in  their hands, the sound of flipping pages. A traditional library, similarly, has a quite distinct sensory profile. Scents of Freshly vacuumed carpets mix with slowly disintegrating paper and the hushed sounds buzzing fluorescent bulbs. The lightly dusted, thickly bound books align row after row, adorned with laminated white stickers with small black letters and numbers, guiding readers to textual treasures organized by genre, topic, author, and title. These sensory stimuli may evoke calm, excitement, comfort, all of these things together. Indeed, being in a library has a feel. To fear the loss of this somatic experience, this “feel” is a legitimate concern. With a new kind of library, and a new medium for text, a particular sensory experience will, in time, be lost forever.

their hands, the sound of flipping pages. A traditional library, similarly, has a quite distinct sensory profile. Scents of Freshly vacuumed carpets mix with slowly disintegrating paper and the hushed sounds buzzing fluorescent bulbs. The lightly dusted, thickly bound books align row after row, adorned with laminated white stickers with small black letters and numbers, guiding readers to textual treasures organized by genre, topic, author, and title. These sensory stimuli may evoke calm, excitement, comfort, all of these things together. Indeed, being in a library has a feel. To fear the loss of this somatic experience, this “feel” is a legitimate concern. With a new kind of library, and a new medium for text, a particular sensory experience will, in time, be lost forever.

The new space, constituted by a new medium, will not, however, be without a “feel” of its own. The glowing screen; the smell of plastic mixed with cheap screen cleaners; the sound of softly clacking keys; the visual effect of a slightly warped screen against the faded grey of an old kindle; the anticipation of an hour glass or repeating circle, accompanied by the excitement of a pop-up: “your document has arrived.”

In the course of a couple generations, if digitized libraries become the new norm, new sensory profiles will reshape the somatic nostalgia of an entire population. This historical moment is at once terribly sad and incredibly sociologically interesting. We are at an intersection of somatic transition. Many will experience great and legitimate loss, unable to pass down some of their most meaningful sensory experiences to their children and grandchildren. Perhaps, at some point, losing the sacred spaces in which they get to revisit these sensory experiences themselves. Meanwhile, the young are in the midst of a great construction, building the sights, sounds, and smells of future whimsy.

Jenny is a weekly contributor to Cyborgology and avid smeller of both books and screens. Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

Comments 9

Barry Wellman — September 18, 2013

Different types of libraries have different smells. Descending to the bowls of Harvard's Widener Library is much different than your neighborhood branch or the roadside library in England converted from a red telephone booth. Indeed, in the 1960s, someone was discovered living in the lower depths of Widener - cot, hotplate and all -- in the seldom-visited Sanskrit section.

Mace Ojala — September 21, 2013

You're forgetting the multitude of smells people bring in to the library :)

I am not sure how much of a joke it is and if it can actually be purchased, but i have seen an odorant with that musky smell of books. You can spray ot on your laptop/ebook reader and it will be just like thr "real thing".

jennydavis — September 21, 2013

OH. My. Gosh. I currently have zero decorations in my new JMU office. This might have to be the first.

The Feel Of Books | The Penn Ave Post — September 21, 2013

[...] Sullivan The all-digital Bexar County Bibliotech Library opened in Texas this week. Jenny Davis wonders how reading culture will change as digitization becomes more dominant: A traditional library [...]

Krista — September 22, 2013

The vast majority of people, prior to the development of US public libraries and the concept of open stacks, never knew what it was like to smell a library. Only the rich, powerful, or clergy gained entrance to stacks in Europe or owned their own. Maybe that is why I like to think of musty old book smell as belonging to the people, for in this country it can.

All Libraries are “Real” » Cyborgology — October 4, 2013

[...] idea of books, one that approaches fetishization in its own right. We experience them by touch, by smell – both the books and by extension the spaces that the books are in. And we experience books [...]