Let’s get the obvious out of the way: Elysium was trashy action flick. It sacrificed any pretense of plot or character development to maximize the number of fight sequences and explosions. It’s clearly geared toward the X-Men 7/J.J. Abrams crowd. However, Elysium does accomplish a few things worth considering:

- It injects a class narrative into an action movie—a genre that has been intellectually moribund in recent decades.

- It offers a revolution (as opposed to reform) narrative.

- It envisions a dystopia arising more from state neglect than from state control.

- It avoids technological reductionism.

(Note: Spoilers to follow)

Class Conflict

Americans are notoriously bad at at discussing–or even acknowledging–class (compared to, say, our British counterparts who regularly portray class conflict in popular shows such as Downton Abbey or Upstairs, Downstairs). While Elysium is, in many ways, a standard Hollywood blockbuster, director Neill Blomkamp’s South African heritage seems evident in the film’s backdrop of class-based oppression. The film’s namesake, Elysium, is a city-sized space station orbiting the Earth; it was built so that the world’s elites can spatially isolate themselves from the global poor that vastly overpopulates the near-future planet. The poor remain bound to the planet’s surface where their labor is exploited by a police state to further enrich the the elites of Elysium. While there are villains in the movie, they are serve as obstacles in a quest to confront a greater evil: the injustices inherent in the social system. The movie closes not after the final villain is defeated, but after the central computer system is reprogrammed to give all people citizenship to Elysium (and the rights to health care and freedom of travel that this citizenship affords them).

Contrary to our national mythology—The American Dream—which suggests everyone can achieve prosperity if he or she works hard enough, Elysium works from the premise that there is only so much room on the ship of privilege and that this ship needs to exploit a lot of outside labor to stay afloat. There is no rising tide to lift all boats. Instead, privilege for some must come at the expense of others.

Revolution vs. Reform

Revolution narratives were commonplace in the collective imagination of the West in the early to mid 20th Century. Fritz Lang’s early dystopian classic Metropolis (1927), for example, ends in a violent workers’ revolt. In the past several decades, most prominent activists, academics, and artists have conceded that capitalism is impossible to displace (at least in the near-term), arguing that it is more productive to put energy towards regulating it or towards hastening its (supposed) evolution towards something more benign. Rather than imaging the overthrow of an unjust system, we are now more often confronted with narratives about how one individual maintain his or her humanity in the face of a system that is impossible to escape (e.g., Blade Runner [1982], Brazil [1985], Gattaca [1997], Code 46 [2003] . Elysium, however, imagines a wholesale (and literal) reprogramming of the social apparatus, where healthcare is redistributed to all according to need and where the police now serve the people not the state.

Dystopia of Neglect (vs. Dystopia of Control)

Georg Orwell’s 1984 (1949) is perhaps the most-cited English-language dystopian narrative. It, like most classic dystopian narratives, imagines a world in which the state (or whatever other bureaucracy maintains social order) exerts excessive control over our lives, limiting personal freedom. In Elysium, on the other hand, the grim conditions experienced by the protagonist is more the product of under-regulation of the lives of individuals than of over-regulation. In other words, conditions are so terrible for the characters because their well-being is largely neglected or ignored.

In dystopias of neglect, scarce resources and opportunities go to those who are inside the system and sophisticated techniques/technologies are employed to ensure the exclusion of all others. The injustice is not in how people inside these societies are treated but in how “social sorting” is conducted to determine who has a right to participate in the system at all. The victims of the system are outsiders to its world of privilege left to fend for themselves.

The dystopia of control reflects a rather conservative fear of losing the freedom and privilege that one already has, while the dystopia of neglect stems from a fear of being permanently shut out from the opportunities one has yet to access. The dystopia of neglect is the present made permanent—the rigidification of existing global inequalities.

(Code 46 and Sleep Dealer also both recently tackled the theme of neglect [2008].)

Technology is not Sinister but also not Neutral

In many dystopian narratives, technology itself becomes the antagonist. This ludditic impulse is most evident in The Matrix (1999),where technology controls not only the social order but also the very fabric of (simulated) reality. In such films, freedom depends on whether the characters manage to destroy the technologies used to oppress them.

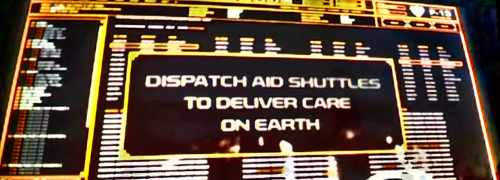

While near-future technologies are used to facilitate oppression in Elysium, the characters have no interest in destroying that technology. Instead, they are fighting to share access to and control of the technology. The protagonists’ main motivation, in fact, is that they need Elysium’s technology to improve their lives, particularly the medical regeneration stations that can cure virtually any ailment. Once the protagonists manage to seize control of the central computer system, it automatically deploys mobile healthcare units back to Earth to treat all the new people it now registers as citizens.

Elysium also avoids simplistically portraying technology as politically-neutral. For example, the program implanted into the lead protagonist’s head is lethal when extracted. This technology intrinsically inhibits sharing and is thus anti-democratic. The protagonists are not simply interested in technology for technology’s sake; rather they are specifically interested in the technologies that promote democratic and humanist values.

Comments 5

Doug Hill — August 24, 2013

Glad to see this piece, PJ,and appreciated very much the points regarding class issues and dystopias. (Haven't seen Elysium, but your comments make me want to.) One the key victories of the monied class in our time is its success in convincing lots of people that class isn't a legitimate issue, and that "class warfare" is a profanity never to be uttered in polite company.

I wonder about your use of "luddic" as a seemingly pejorative adjective, especially in this context. The Luddites were not blindly and stupidly attacking machines out of fear of technology. They were protesting the oppressive use of technology by the mill owners. Nor were the fears of the Luddites regarding the machines misplaced: they DID end a way of life as well as a way of making a living.

A recent piece in the Guardian, though not especially coherent, touches on these points. http://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2013/aug/23/science-policy-the-nsa-files?commentpage=1

jake3_14 — August 31, 2013

Doug Hill — this essay is at least twice as good as the movie.

What if We Are Seeing a Dystopia in The Making – Caused by The Third Industrial Revolution Finally Reaching its Tipping Point? | oserblog — September 29, 2013

[...] It would, of course, be theoretically feasible to avoid such an outcome if the production potential and profits could be widely distributed so that ‘ordinary people’ did not need to work very much – their main function becoming simply to consume (l believe Kornbluth got there early, with his novella The Marching Morons in the 1951, if it wasn’t Keynes a couple of decades earlier). But without a nasty revolution it looks to me more like the coming dystopia of Elysium [...]

Links | ROELOF.INFO — March 15, 2014

[…] http://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2013/08/24/film-review-elysium-dystopia-and-class-conflict/ […]