The idea that technology and techno-scientific urbanization/development is making life more noisy is not new. Luigi Russolo wrote about this in his famous futurist manifesto The Art of Noise. “In antiquity,” he argues, “life was nothing but silence. Noise was not really born before the 19th century, with the advent of machinery. Today noise reigns supreme over human sensibility” (4). Russolo’s manifesto was written in 1913. “ON IT” like usual, The New York Times published a couple of stories about it last week.

While it’s certainly not news that cities are noisy, the Times article does suggest that the politics of urban noise have changed significantly since Russolo’s time. Urban noise works (or produces political effects) differently because it is understood differently–it’s not industrial and machinic, but post-industrial and affective.

The second article linked above treats noise as a toxin that contaminates what you might call our “affect system”–like the body’s limbic system or cardiovascular system, but instead of managing hormones or blood oxyegenation, it manages affective tenor—stress, happiness, well-being.

Beyond harming hearing, chronic exposure to noise increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. Children in classrooms buffeted by outside noise lag behind, and their teachers report lower job satisfaction. Pervasive background noise may damage the hearing center of babies’ developing brains, research has found, possibly leading to auditory and language-related development delays. And though people may assume they have grown accustomed to noise, a constant din, even at low frequencies, often takes a heavy physiological toll. Noise can cause stress even when a person is sleeping.

Noise elevates levels of negative affective response–stress, anxiety, distraction, uneasiness. These negative affects then impede us from functioning at maximum capacity. The problem with noise isn’t aesthetic–it’s not ugly, irrational, or offensive. Noise isn’t disruptive, either; we still go on with our day’s work or night’s rest, just at diminished capacity. Noise prevents us from flourishing. It produces ill health. That’s why it is treated as a toxin.

As with all toxins, exposure to noise is determined by privilege—wealthy Manhattanites can soundproof their penthouses, but Queens residents have to suffer through continued clamor as they appeal to bureaucratic processes designed to regulate noise pollution. So privileged Manhattanites can, like the fabled princess who was so sensitive she could feel a pea under a tower of mattresses, retain their finely-tuned senses/sensibilities.

This association between aesthetic sensitivity and privilege is interesting because it reverses 20th-century trends…the very trends set, in part, by Russolo’s manifesto. Russolo was worried that traditional musical sounds were too pure to have any affective punch:

In the pounding atmosphere of great cities as well as in the formerly silent countryside, machines create today such a large number of varied noises that pure sound, with its littleness and its monotony, now fails to arouse any emotion (Russolo, 5).

Russolo thought we needed industrial noise to reinvigorate art music. “We get infinitely more pleasure imagining combinations of the sounds of trolleys, autos and other vehicles, and loud crowds,” he argues, “than listening once more, for instance, to the heroic or pastoral symphonies” (6). Modernist aesthetics value transgression and difficulty. The ability to tolerate and appreciate noise was a sign of avant-garde taste; so, cultural elites stereotypically valued “noisy” works, while the unwashed masses preferred kitsch. In the Times article, this modernist association between noise tolerance and privilege is reversed: sensitivity is a privilege reserved for those with means to protect themselves from it and preserve their delicate aural/affective palate, and noise-tolerance is the effect of exposure. Sonic ecologies should be (re)purified. You can even see this reversal in contemporary pop music aesthetics: mainstream pop–from the Biebs to Skrillex–is really noisy, while hipsters and NPR listeners prefer traditionally pretty, harmonious, folk-y, “new sincerity”-style artists.

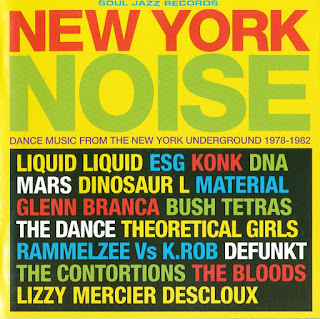

To me, it seems sorta weird to complain about noise in the city that brought us scratching and No Wave (and everyone should check out Caroline O’Meara’s great work on NYC, geography, & No Wave). But then, those were products of the divested city, the Bronx & pre-Guilianni downtown left to “drop dead.” In the redeveloped, fully-neoliberalized contemporary Manhattan, maybe sounds become “noise”–that is, they become a problem–when they are wasteful, unrecycled by-products of other activities?

The article largely discusses noise as byproduct of (re)development, the unattractive waste from capitalist projects. Manhattan residents, given their overall wealth and privilege, are already structurally insulated from such byproducts–it’s not their water that gets contaminated by natural gas fracking, for example. Construction noise, however, can’t be outsourced because real estate redevelopment is necessarily place-specific. Apple can make your iPhones in China, but real estate speculators can’t tear down and rebuild Manhattan real estate anywhere but on site. These redevelopment projects, which intensify and magnify the value of already-valuable property, generate “toxic” byproducts. Noise–especially construction and transportation noise, which is the focus of much of the article–is a “problem” for Manhattanites because it is one of the few byproducts of neoliberal development that can’t be outsourced to less-privileged areas.

“Music is a better noise/Than rumbling catapults/and fumbling cranes” (Essential Logic, “Music Is A Better Noise”).

If noise is so sickening to privileged constitutions, I wonder what this means for the political possibilities of new types of industrial music. What kinds of noises would be musically or sonically toxic (rather than machinic, as in trad industrial, or glitchy, as in cyberpunk)? (Interestingly, toxicity was a common lyrical theme in 90s goth/industrial…but what about musical/sonic toxicity?) How would they work politically?

Those are genuine questions–I don’t even have a tentative response to them. So, if you have any thoughts, I’d be very happy to hear them below.

Follow Robin on Twitter: @doctaj.

Comments 5

elinorcarmi — July 16, 2013

Great article Robin. I also stumbled upon this interesting article.

I think noise as a nuisance is understood as such through a process of social construction; some are more 'tolerated' than others and some are not framed as noise at all, but as you've mentioned - necessary sounds for the city's development.

In addition it could be used as a useful tool for municipalities to enforce power. For example, in my country - Israel - they have just approved a Noise Bill, which means that the police can enter enter homes without warrants (!!) if they have a reason to believe that it causes a "significant harm to public well-being". (http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4402539,00.html) What are the chances this legislation will be abused?

robinjames — July 16, 2013

thanks, elinor! i definitely agree that the acceptability or tolerability of 'noise' is indexed to other social factors, like race, class, and gender. for example, there was a black florida teenager, jordan davis, who was shot because his music was "too loud". i wonder if things would have been different if he was blasting beethoven or johnny cash. in the law you discuss, 'noise' is a proxy for what is probably racial and national 'unruliness'--it will likely be used to enter homes of people who are already considered a "significant harm to public well-being"....

Rich ferrante — July 16, 2013

That penultimate paragraph reminded me of "sonic warfare" by Steve Goodman (kode9), an interesting take on the use, and abuse, of sound.

Mark N. — July 20, 2013

I'm not sure if it's what you're going for, but the genre of Power Electronics aimed at a sort of self-conscious toxicity, in the sense of being unpleasant to its listener, whether through straightforward verbal abuse and/or being musically unlistenable. Its political valence tends rather right-wing, sometimes far-right, though most of the musicians seem coy about whether there is any actual political intent involved or if it's part of the shtick.

By way of roundabout connection to the examples in your post, the guitarist of Essential Logic, William Bennett, went on to form Whitehouse.

Erika — July 22, 2013

Gerogerigegege (http://youtu.be/kYaRV6EwI3U) pops to mind. They are a harsh noise band that's pretty damned toxic, sonically and otherwise. Their politics would be interesting to look into.