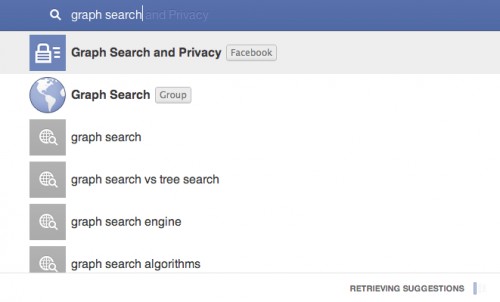

Facebook just enabled its new Graph Search for my profile and I wanted to share some initial reactions (beyond the 140 character variety). Facebook’s new search function allows users to mine their Facebook accounts for things like: “Friends that like eggs” or “Photos of me and my friends who live near Chuck E. Cheese’s. ” The suggested search function is pretty prominent, which serves the double role of telling you what is searchable and how to phrase your search. More than anything else, Graph Search is a stark reminder of how much information you and your friends have given to Facebook. More importantly however, it marks a significant change in how Facebook users see each other and themselves in relation to their data.. You no longer see information through people; you start to see people as affiliated with certain topics or artifacts. Graph Search is like looking at your augmented life from some floating point above the Earth.

Graph Search makes Facebook feel “bigger” and more intimate at the same time. I say bigger because you are no longer an individual who likes The Talking Heads or has too many photos of food. Instead, Graph Search makes me feel as though my friends and I are single instances of Instagramed food within an enormous database of lonely eaters. You just see more of the social landscape and connections come into high relief. Seeing those connections (some of which I saw for the first time) provide an instant “in group” feel. If you didn’t come up in my search for “friends who like cats” you are, by default, a dog person. You are different and you don’t understand my cat tree.

Not only does your perspective change, but the order with which I think about my friends and our mutual interests change as well. Facebook has outgrown its namesake, and now resembles something closer to a social search engine. (Something Zuckerberg has wanted for a long time.) This shift, from a book of faces to an indexed catalogue of varying living and non-living objects, means Facebook can update me on things as well as people. Whereas before Graph Search you could search for people and groups of people (including bands and companies), now you can search for just about anything and see how it relates to your friends. It’s a total deconstruction of my augmented life. Obscure trends are suddenly completely obvious. For example, when I searched “Music my friends like” the top hit (60 friend likes) was “Ingtzi” my friend’s DJ-ing name. A Facebook PR person would call your attention to the fact that Ingtzi isn’t the most popular musician among my friends, but the most unique result among my particular friend distribution. (I have no doubt “The Beatles” or something equally generic outnumbers Ingtzi.)

In order to do work to lots of different people, you have to slice and dice them into many different kinds of subjects. Graph Search could not exist without all of the standardized “likes” and relationship status fields that turn humans into usable data sets. This process of standardizing and groups is not new: governments have been turning people into pieces of information for a long time. Towards the end of his career, Michele Foucault became intensely interested in what he called governmentality or how people become governable populations and civic-oriented citizens. He wanted to know how individual people become compatible with government bureaucracies and soverign entites. After all, you can’t have a Department of Health if you don’t have a body of knowledge and a set of practices that let you treat individuals like a bunch of medical patients or biological entities that contract and transmit disease. Graph Search works in the same way. Standardized “like” buttons and constant requests to “tag this photo” or “Add your hometown” not only encourage you to enter more data, they also make you compatible with search algorithms.

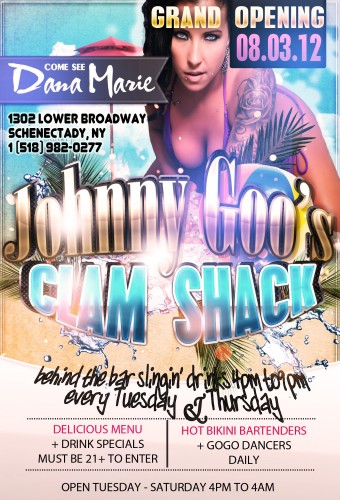

This process is mutually shaping. Just as Facebook makes you compatible with search, your constant searching starts making you think like the algorithm. You might base playlists for parties on Graph Searches, or plan outings based on search results. Your online searches will have consequences offline. Intriguingly, Graph Search seems to work better when I ask very specific things. When I search for “Photos of Food” the top three photos are 1) a picture of the Waffle House Museum sign, 2) a picture of my cousin with his wife, and 3) a sketchbook drawing of a friend. The next four pictures look like stock photos of pizza. I also got this strange (and outdated) promotional sign:

Perhaps image searches are still best left up to Google. For now, I’ll choose my search engine based on two kinds of questions. Questions that start with “what” are meant for Google and questions that start with “who” are Graph Search questions. (Apparently “who” questions that Facebook can’t answer will go to Bing. Good for Bing.) The commentariat seems to believe that Facebook is looking to compete with Google in search, and such questions are best left to business analysts. For me, it will be interesting to see how using both of these search engines will change personal decision-making. I also can’t wait for the inevitable Google is Making Us Stupid corollary: Graph Search is making us Anti-Social.

Comments 10

SAA — January 30, 2013

I loved this write up. Thank you for sharing!

Ok, I'll bite:

Facebook Graph Search may make us "Anti-Social," but not in the way you might be thinking, it's potential to do that will be covert and indirect.

Your statement: "If you didn’t come up in my search for 'friends who like cats' you are, by default, a dog person. " is an excellent example of the kinds of wrong assumptions people may make about others based on the limitations of Graph Search.

Just because someone doesn't "like" cats, doesn't mean they like dogs, but Graph Search doesn't have way to compensate for that.

The biggest problem with Graph Search that I can foresee is in the assumptions that people will make based on incomplete data of a very limited nature.

Graph Search isn't really making us Anti-Social, but it is showing a huge capacity to make us careless about conclusions, which is just as socially dangerous, if not more so than stupidity.

Being careless about conclusions about people based on incomplete data could result in a lot of unintended behavior that could be categorized as "Anti-Social." Given Facebook's reach into businesses, government and educational interests, this could have larger, more far reaching consequences.

Joshua Comer — January 31, 2013

That you're seeing depth-first associations (those things uniquely prevalent among your friends) instead of the breadth-first associations (The Beatles) suggests that the Google bombing approach won't work, or at least not in anything like the same way. You're going to see success in your hypothetical efforts at re-associating the administration with drone warfare if your closest friends go along with the scheme, but your impact will be limited to those nodes. Even if you engineered a broad based movement to re-identify some major figure, those outside of the movement are still not going to be able to see it, let alone see it based on normal search practices. You and yours can influence your child nodes, but you will have a very limited effect on sibling nodes, and a severely curtailed ability to judge your efficacy. The way in, both in terms of seeing effects and managing them, is going to be through the marketing packages that will let you view and persuasively intervene in those broader topologies.

Joshua Comer — January 31, 2013

It makes the move Facebook made when they started limiting the reach of status updates unless you promoted your status look like an antiquated broadcast model effort for information control.

There is a lot to consider here.

SAA — January 31, 2013

Joshua, in both are you referring to David's comments or mine?

If you are commenting on my comment, I would add that I'm specifically addressing rumor development as an aspect of the aggregate of individual graphs in the collective psyches.

For example, what sort of societal shift is there as each individual makes assumptions and conclusions based on thin and incomplete data in their own graph and they become combined as an aggregate 'voice'?

I refer to broader scale implications of incorrect conclusions and assumptions based on simple individual graphs that people take with them into other facets of their lives.

Joshua Comer — January 31, 2013

I meant to primarily address David's comment, sorry for not making that clear.

I think you and I are on much of the same page here.

I think it is important to consider how the patterns of inference you are concerned with will continue to assume Facebook as part of a broader sphere of information-gathering methods and resources when in fact it is in many ways narrowly encapsulating. Google in many ways leads people to expect a different kind of information gathering, an auto-fill-in-the-blank survey of frequently referenced concerns and sources, that the specificity and assumption of shared knowledge upon which Graph Search functions does not share.

Thus far it might seem that this is just another twist on the much-worried-over idea of an echo chamber, but it is a bit different. You can accidentally bump against the discursive walls of most echo chambers by saying something inappropriate to the in-group, or be forced to recognize those limits when you engage people with divergent viewpoints on a public forum - say, a newspaper website. With Graph Search there isn't the same opportunity to encounter those limits or to recognize them through a shift in perspective. Now, why is that?

David comments in his blog post on the tags, likes, and other information through which the tight-knit associations of Graph Search are based and brings attention to how they naturalize and encourage the sharing of further personal information in a ready-to-search format. What I would add to that given our shared concerns with the inferences people make is the significance of those social markers having no analog outside of Facebook, making many methods for comparing information impossible.

SAA — January 31, 2013

You wrote: "Now, why is that?"

At this point, I refer you to our (Applin, Fischer) work on PolySocial Reality (PoSR) at

http://www.posr.org

PoSR describes the multiple, sometimes overlapping, network transaction spaces that people traverse synchronously and asynchronously with others to maintain and use social relationships; a conceptual model for the global interaction context within which people experience the social mobile web and other forms of communication and social interactions whether immediate or mediated by technology.

PoSR defines relations across the aggregate of all the experienced ‘locations’ and ‘communications’ of and between all individual people in multiple networks and/or locales at the same or different times. PoSR is based upon the core concept that dynamic relational structures emerge from the aggregate of multiplexed asynchronous or synchronous data creations of all individuals within the domain of networked, non-networked, and/or local experiences.

Papers can be found in order of publication here: http://posr.org/wiki/Publications

Joshua Comer — January 31, 2013

To word all of that more succinctly: There may be competition between Facebook and Google over social information, or on the proprietary formatting of those social factors, or marketing dollars. But when it comes to the decision-making processes shaped by those factors Facebook is moving away from such clear-cut competition and inhibiting our ability to understand those processes by comparing search results. Google carefully tends its formulas for how personalized we like our search results, and Facebook is moving toward operating more on the other side of that line of customization (if it even makes sense to suggest such an opposition) while ensuring that we can have only a vague hunch about where it is drawn.

nathanjurgenson — January 31, 2013

Dave, love love this post! though, do people really understand the Graph search "friends who like cats" as literally friends who like cats? or do/will users understand the search results as "my facebook friends who clicked "like" for cats."

this is a significantly different interpretation in at least 3 important ways.

1- we know facebook friends are different than friends. we have facebook friends we dont consider friends and maybe even friends not on facebook. this is no secret.

2- we know some people who like cats didnt click "like" on the facebook page for cats. indeed, it would be nearly impossible to click like for every facebook/wikipedia entry that we actually like. and there might be things we like that do not have corresponding facebook entries, like, i dont know, the feeling of that first night in freshly washed bed sheets (tho, i wouldnt be surprised if there's a page for that). also, there are things someone might like, but would not click "like" for, eg, defecating is something people tend to like without admitting it (asking about it is a good way to measure if your survey respondents are prone to socially desirable rather than accurate answers).

3- and we also know that people click "like" on something they dont actually like. irony, dishonesty, changing tastes, whatever, our list of likes might contain things we dont.

while people might not generally think of all this explicitly, i think these understandings are or will be assumed by even the average facebook user when doing the search, which somewhat tempers your conclusions here...