Please excuse the Atlantic Magazine-worthy counterintuitive article title, but its true. The Consumer Electronics Show, more commonly referred to as CES is cheesy, expensive, and out-dated. I used to really love CES coverage. It was a guilty pleasure of mine; an unrequited week of fetishistic gadget worship. I savored it all: the cringe-worthy pep of the keynote addresses, the garbled and blurry product videos taken by tech blog contributors, the over-hyped promises that never come true. But this year, after watching the entire 90-minute Waiting for Godot-style keynote, I don’t see the point anymore. All the coolest stuff was made by indie developers and they introduced their products months ago, through awkward in-house YouTube videos. CES might be convenient for gigantic multinational corporations, but what’s in it for the Kickstarter-fueled entrepreneurs? Is a Las Vegas trade show the best medium to show off your iPhone-controlled light bulb, or e-ink wrist watch? Why does half of Maroon 5 need to half-heartedly churn out three songs at the end of an hour-long product description? The industry has matured, and CES is no longer sufficient.

Cyborgology has been in a confessionary mood as of late, and I’ll do the same: I watch every Apple keynote. When it was Steve, I marveled at his signature Reality Distortion Field. Small, incremental changes to software I would never use were absolutely riveting. (Coverflow on my iPod Touch? Incredible!) The same signature polish and fascistic attention to detail that we love in their products was there on the stage. When Maroon 5 played an Apple event, they made sure to get the whole band, and Adam Levine did not get to talk. Even the worst moments in Apple keynote history were met with total confidence. Steve might say, “Well, its pretty awesome when it works.” and then move on. In contrast, almost everything demoed at the CES keynote worked perfectly but the whole production had the finesse of a middle school dance.

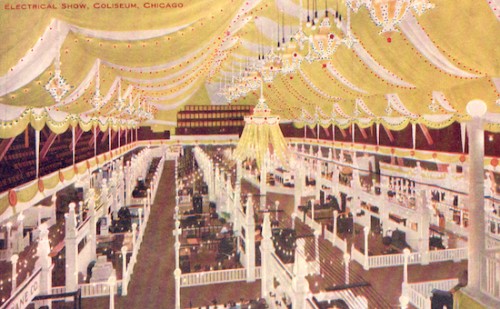

CES is, in may respects, and exercise in imagining a world without Apple. (Or Amazon, or Facebook, or Google) Until this year, the keynote was always given by Microsoft’s CEO. (Now, Microsoft isn’t even exhibiting.) Bill Gates and later, Steve Ballmer would give a sort of State of the Union address: Intel processors were still conforming (and confirming) to Moore’s Law, AMD was keeping the prices below monopoly rates, and Windows XP was about to get a new service pack. The rest of the show was a demonstration of the vast ecosystem of peripherals and software that could play within the walled garden of Wintel. The walls saw their first major cracks in 2001 when the iPod was introduced. Suddenly one of the most popular devices to be plugged into a computer was nowhere to be seen on the CES floor. (Apple stopped going to CES in 1992.) Then came the iPhone, the iPad, the rising adoption of Google products, and finally the thousands of products made by small design outfits were garnering much more attention than the latest additions to Windows 8.

Microsoft used to be an obligatory point of passage, but now they have been reduced to another contender in highly competitive markets. They’re not has-beens, but in every major category (with the big, but debatable category of gaming) they are perceived as also-rans. Windows 8 is off to “a slow start”, no one willingly decides to “Bing” something, and the Zune is all but a distant -unpleasant- memory. More important than the fall of Microsoft however, is who rose to take their place. The keynote for the Consumer Electronics Show did not go to a consumer electronics company. The dubious honor went to Qualcomm’s CEO Dr. Paul Jacobs. Qualcomm makes 3G mobile chipsets. You, as a consumer, don’t go out and buy a Qualcomm phone or Qualcomm e-reader. Companies choose to incorporate Qualcomm technology in their products. Its as if the Detroit Autoshow were headlined by the company that makes your timing belt. What does it mean when CES is run by a chipset maker? Matt Buchanan from Buzzfeed goes so far as to say CES is dead because hardware is dead: “Hardware […] has become increasingly commoditized into blank vessels that do little more than hold Facebook and Twitter and the App Store and Android and iOS.” I don’t think hardware is dead, not by a long shot. If anything, the “Internet of Things” (Jacobs insisted on calling it the Internet of Everything) signals the renaissance of hardware. But hardware will look more like a notebook with stickers, or Arduino than a desktop computer. Qualcomm’s ascendancy to the keynote demonstrates a willingness (or concession) on the part of CES organizers to let big companies act as providers of infrastructures and core technologies, and let smaller startups sell the final consumable product. If that’s the case, then CES is going to look very different in years to come.

The Verge’s Adrianne Jeffries observes that a friendly confederation is forming amongst the crowdsourced companies at CES. The “smartwatch” category is almost entirely filled with Kickstarter projects and they all made efforts to meet each other. A meritocratic hierarchy is already forming amongst these entrepreneurs: newbies are seeking out experienced veterans to talk shop and get fundraising campaign tips. Scott Wilson, maker of the very successful LunaTik touchscreen watch kit describes a steady stream of fellow Kickstarter-funded entrepreneurs that want nothing more than to swap campaign stories: “Overall, there is this overarching inspiration for doing your own thing, and that is partly driven by Kickstarter.” Jeffries also quotes Pebble CEO Eric Migicovsky as saying, “CES probably has the largest amount of Kickstarter backers in the world concentrated in one place,” Every conversation on the show floor seems to loop back around to the phrase, “we/they did a Kickstarter and raised X.”

The Verge’s Adrianne Jeffries observes that a friendly confederation is forming amongst the crowdsourced companies at CES. The “smartwatch” category is almost entirely filled with Kickstarter projects and they all made efforts to meet each other. A meritocratic hierarchy is already forming amongst these entrepreneurs: newbies are seeking out experienced veterans to talk shop and get fundraising campaign tips. Scott Wilson, maker of the very successful LunaTik touchscreen watch kit describes a steady stream of fellow Kickstarter-funded entrepreneurs that want nothing more than to swap campaign stories: “Overall, there is this overarching inspiration for doing your own thing, and that is partly driven by Kickstarter.” Jeffries also quotes Pebble CEO Eric Migicovsky as saying, “CES probably has the largest amount of Kickstarter backers in the world concentrated in one place,” Every conversation on the show floor seems to loop back around to the phrase, “we/they did a Kickstarter and raised X.”

Do Kickstarter firms gain anything from CES? Successful Kickstarters that also had a presence at CES are usually described in the media as “graduating” or “moving on” to CES as if inclusion in the show automatically denotes an arrival to “the big leagues.” Its too early to draw any hard conclusions, but beyond networking I do not see how these companies benefit from flying themselves (and all of their equipment) to Las Vegas. Anecdotal evidence suggests that, if anything, big companies wish they could get in on Kickstarter. The buzz for your product is started months in advance, and if you reach your funding goal before CES, you have a pretty compelling business plan. Conferencing is probably better for getting your gadget on brick and mortar store shelves, but that seems more like a service Kickstarter doesn’t offer yet, rather than a strength of CES.

I want to return now, and conclude with a few more words on the concept of a trade show. Trade shows are always equal parts pomp and propaganda, but the propaganda sucks and the pomp is expensive. No adult with even the smallest shimmering spark of creativity would latch on to terrible, contrived terms as “Mobile Generation” or “born mobile.” Nor are they going to take your stilted and vaudeville levels of over-wrought delivery as honest or even authoritative. What good does it do your company when your CEO stands up on a stage and talks like a 10-year-old kid with a new Pokémon card? (And this chip does this, and if you bundle it with this it can do all of these things but not as good as this one which is better.) Why should your, otherwise proud employee, be dressed up like a “birdketeer” in a fake kitchen? The social net is too personal, too intimate, to be captured by hokey business jingles. There’s too much of myself –sensitive, identifying information as well as emotionally evocative content– to watch overt salesmanship. This isn’t toothpaste brand loyalty, this is my phone you’re talking about. Start taking this stuff seriously. If you insist on presenting your work like its a Slapchop, go hire Ryan Seacrest. CES is always described as a fortune-telling device. To gaze upon the showroom floor is like looking at a Best Buy 10 years in the future. CES has to be more than a big box store at the other end of a temporal rift. It needs to demonstrate what my life is like after I leave the store. What will my daily life be like? Perhaps its time that the CES organizers consider putting together a World’s Fair?