Given that we’re not in the habit of thinking too much where our technological passions might lead us, I’ve been heartened over the past year to see an unusual willingness to confront the potentially devastating impact of the robotics revolution on human employment.

It was a question that was hard to avoid, given the global recession and the widening gap between rich and poor. It’s obvious that rapid advances in automation are offering employers ever-increasing opportunities to drive up productivity and profits while keeping ever-fewer employees on the payroll. It’s obvious as well that those opportunities will continue to increase in the future.

Some credit for opening up the conversation on the implications of this progression goes to two professors at MIT, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee. Their book Race Against the Machine, published late in 2011, had a man-bites-dog quality that attracted a lot of attention. We don’t necessarily expect experts from the temple of technology to question whether technology might be leading us in directions not entirely favorable to humankind.

“The tone of alarm in their book is a departure for the pair,” said the New York Times, “whose previous research has focused mainly on the benefits of advancing technology.”

A series of similar assessments appeared at intervals through the year, among them an essay by Christopher Mims in MIT’s Technology Review in May (“Is Automation the Handmaiden of Inequality?“), an Atlantic.com commentary by Moshe Y. Vardi, a professor of computational engineering at Rice University, in October (“The Consequences of Machine Intelligence“), and three New York Times pieces in December, two by Paul Krugman (“Rise of the Robots” and “Robots and Robber Barons“), and one by Brynjolfsson and McAfee (“Jobs, Productivity and the Great Decoupling“).

Also in December, the perennial technological enthusiast Kevin Kelly weighed in with his views on the automation revolution in a Wired cover story (“Better Than Human,” published online in December, in print in January). Although Kelly skipped over the short-term challenges that worry Brynjolfsson and McAfee, in the end his conclusion was the same as theirs: The future for workers depends not on competing with machines but on learning to leverage the advantages they offer to get ahead. As Kelly put it, “This is not a race against the machines,” he wrote. “If we race against them, we lose. This is a race with the machines….Let the robots take the jobs, and let them help us dream up new work that matters.”

Probably the oddest recent entry in this discussion, and the one that intrigued me most, came not from an economist or journalist, but from a press release issued by a company hoping to capitalize on the robot revolution. I’d like to dwell a bit on the details of that release here, seeing as how it had some outstanding man-bites-dog qualities of its own.

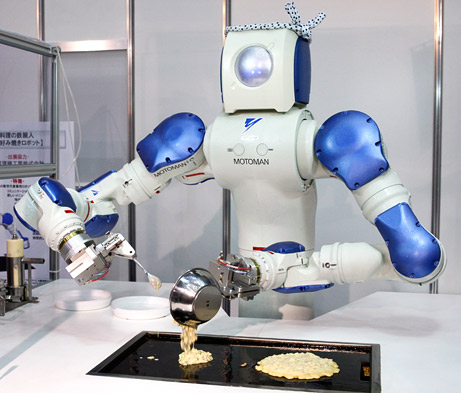

The release was issued in November by a San Francisco-based startup called Momentum Machines. It announced the arrival of a hamburger-making machine that will revolutionize fast food as we know it. (The robot pictured at the top of this piece is from a different company.)

The surprise isn’t that the release promises a product with revolutionary benefits. The surprise is that it acknowledges those benefits might be accompanied by some troubling side effects. In doing so the release embodies with unusual clarity the tension that exists between those two conflicting outcomes.

Momentum Machines claims its hamburger machine can churn out 360 fully prepared and packaged hamburgers an hour. Not just ordinary burgers, but gourmet burgers, expertly cooked and seasoned to order. The quality of the product, however, isn’t the principal value the release seeks to promote.

Its headline centers instead on the machine’s astonishing economic benefits. “The Restaurant Industry Is The Most Labor Intensive Industry In The Country,” it reads. “Our Technology Can Save The QSR [Quick Service Restaurant] Industry $9 Billion/Year In Wages.”

The release goes on to promise that Momentum Machine’s machine (they’ve yet to come up with a name for it) “replaces all of the hamburger line cooks in a restaurant. It does everything employees can do except better.”

The unexpected twist appears in a three-paragraph statement at the release’s end.

Apparently recognizing that its earlier promise to replace every line cook in the business carries some unpleasant implications, for line cooks if not their employers, the company expresses a desire to help retrain people displaced by its technology. To help smooth their “transition,” the company says it will offer opportunities for technical education at a discount. The suggestion is that fry cooks will be transformed into engineers, after which they will participate in further automating the fast food industry.

The release then ventures into territory seldom explored in the annals of public relations: economic theory.

“The issue of machines and job displacement has been around for centuries,” it says, “and economists generally accept that technology like ours actually causes an increase in employment.”

This increase is the result, the release says, of three factors: New employees are hired to build the robots; the robots allow the company to expand its “frontiers of production,” which requires more employees; and automation produces savings that can be passed along to customers, thereby stimulating the economy.

“We take these issues very seriously,” the release says, “so please feel free to tell us how we can help with this transition.”

The release also encourages anyone with questions to get in touch, so I did. I asked for any references the company could provide to support its contention that economists “generally accept” that technologies increase employment, and also for more information on the retraining assistance the company planned to offer displaced employees.

To my surprise, a couple of weeks later I received a response from the Founder and President of Momentum Machines, Alexandros Vardakostas. His note was cordial, but not very enlightening. It provided no direct answers to my questions, only a link to a Wikipedia article on technological unemployment, aka “the Luddite Fallacy.”

“Hi Doug. Hope all is well you,” Vardakostas wrote. “Read this to learn more. Warm regards. Alex.”

True enough, Wikipedia’s article does describe the theories of a number of economists who agree that technological advance ultimately leads to an increase in employment. It can’t be considered an unqualified endorsement of that position, however, given that Wikipedia says its “factual accuracy” is disputed, and that it needs “additional citations for verification.” The article also pays little attention to whether today’s revolutionary advances in automation may be creating changes in the economics of labor that render previous theories, even if they were historically true, obsolete. That’s the question asked by most of the articles I’ve cited above.

As we rush toward a super-automated future, plenty of other questions remain unanswered. Brynjolfsson and McAfee, for example, propose innovation through entrepreneurship as a leading solution to employment stagnation, and toward that end recommend various deregulatory measures that will allow new businesses to flourish unencumbered.

I’m no economist, but it seems fair to ask whether measures of the sort they prescribe might simultaneously open the way for even greater exploitation or elimination of labor. Automation typically puts more power in the hands of management, after all, and there’s no guarantee that the vast majority of post-automation jobs will be any more satisfying, economically or spiritually, than the jobs they replace.

For example, Brynjolfsson and McAfee cite as models for the future the thousands of entrepreneurs now exploiting the new opportunities for employment offered by the likes of eBay, Amazon Marketplace, Apple’s App Store, and Android Marketplace. Even if we take for granted that such traditional benefits as health insurance, vacation pay, maternity leave, and pensions are off the table, one wonders how many of those entrepreneurs are making what used to be considered a middle-class income.

Not many, at least in the apps market, according to a recent article in the New York Times. The article makes it clear that winning big in that race with the machines is only slightly more likely than hitting it big in the lottery, and that the people who are really cashing in on the app market are the stockholders of Apple and Google. The headline tells the story: “As Boom Lures App Creators, Tough Part Is Making a Living.”

That article demonstrates perfectly a phenomenon Brynjolfsson and McAfee do address: The emergence, due to the unprecedented economies of scale offered by various technologies, of a super-star marketplace, one in which a few people become fabulously wealthy while everyone else scrambles desperately to break into their golden circle. Kevin Kelly’s vision in this regard is positively Panglossian. Let the machines take over the jobs, he says, while we dream of new work that matters. Take it from one who knows: You don’t get paid for dreaming.

Perhaps the most pressing question is whether an economy shaped by super-automated techno-entrepreneurs will be sustainable. We have an abundance of evidence today that another historical truism of economic theory – that growth solves every problem – may also be obsolete. Certainly the environmental disasters we’ve created suggest that perhaps the time has come to consider a different option: restraint.

Momentum Machines, for example, believes that technologies like its hamburger machine will open new “frontiers of production.” Forgive me, but I’m not sure the frontiers of production opened by previous advances in fast food technology have proved entirely salubrious.

These are some of the reasons why I was hoping Momentum Machines might provide more detailed answers to my questions. I’ve sent Alex Vardakostas a second email, asking for elaboration and passing along links to the aforementioned articles. So far no response, which could mean he’s disinterested in further discussion, or simply that he’s too busy opening new frontiers of production to entertain quarrelsome emails from bloggers.

Doug Hill is a journalist and independent scholar who has recently completed a book on the history and philosophy of technology. This post also available on his blog The Question Concerning Technology.

Comments 3

Doug Hill — January 22, 2013

Anyone coming to this essay late might want to note that on January 22 I posted an update on my blog, explaining that Momentum Machines has toned down its original press release. Most of its original claims remain intact, but the headline and the tone overall have been softened quite a bit.

Here's a link to my update: http://tinyurl.com/bdynn4x

Thomas J. Coleman — February 6, 2013

I agree with your uncertainty that "the frontiers of production opened by previous advances in fast food technology have proved entirely salubrious" but have a feeling that Ray Kroc, the late developer of McDonald's, is "lovin' it" insofar as mechanization continues to take command - assuming he is presently capable of doing so.

http://www.bookforum.com/inprint/1701/5379

Doug Hill — February 6, 2013

Thanks Thomas. Ray Kroc has passed on, but his legacy of mechanization is all-too-alive and well, spreading inexorably across the American landscape. Appreciate also the reference to Gideon's remarkable book. His chapter on mechanized bread was especially prescient in light of Kroc and his heirs. In fairness I should note that (as the late Nora Ephron was fond of saying) today we are enjoying a sort of Golden Age of Bread, as the craft of fine baking has become newly appreciated in response to mass-produced junk bread. Momentum Machines wants to have it both ways: mass production of gourmet burgers. We'll see. Starbucks, I have to admit, makes a fine cup of coffee.