In the aftermath of what both sides agree was the most substanceless presidential election in our nation’s history, some variation of the phrase “post-truth politics” has begun haunting the pages of op-eds and news show roundtables (Seriously, its everywhere. Here’s the first five that I found: one, two, three, four, five.). To say that we live in an age of “post-truth politics” isn’t totally inaccurate, nor is it unworthy of the attention it is getting, but the discussion has yet to truly wrestle with the characeristics of commodified information. Information can be true, and it can be false, but how that information is disseminated, used, and ignored is what truly matters. Information doesn’t (just) want to be free, it also wants to be exploited.

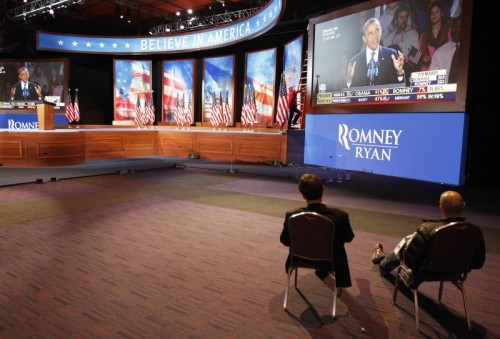

In what is sure to go down as one of the most profoundly ironic moments in American presidential campaign history, the Romney campaign was blinded by its own half-truths and outright lies. They believed “unskewed polls” and isolated themselves in a pasty-white bubble of racism and elitist condescension. As Maureed Dowd put it:

Romney and Tea Party loonies dismissed half the country as chattel and moochers who did not belong in their “traditional” America. But the more they insulted the president with birther cracks, the more they tried to force chastity belts on women, and the more they made Hispanics, blacks and gays feel like the help, the more these groups burned to prove that, knitted together, they could give the dead-enders of white male domination the boot.

The vacoousness of the this race had a lot to do with the candidates’ uneasy relationship with their base. Both Romney and the President stood to benefit from saying as little as possible. Romney could not win battle ground states without alienating the historically vindictive Socially Conservative Base. Women’s health is the obvious example, but so is alternative energy (swing states also have lots of green jobs), and the bailout of car manufactuers (very popular in, ya know, places that build cars). Obama had (and continues to have) a hawkish war record that would make any Republican proud, but stands to lose a largely anti-war base.

Why then, in “the information age,” did we know so little about our presidential candidates? The typical answer is made of equal parts Aldous Huxley and Evgeny Morozov: the Internet lets us say more, but what we actually end up saying is more distracting than informative. We are so over-stimulated that the important stuff either gets lost in the cat videos, or never made at all. Political parties might not make cat videos, but they will manufacture distracting stories to filibuster a news cycle. Eric Alterman writing for The Nation gives us a perfect example:

Remember Condoleezza Rice’s vice presidential candidacy? It was based on nothing more than an anonymous item appearing on the Drudge Report, transparently designed to change the subject from Romney’s refusal to divulge decades of his tax returns.

Granted, stories like Rice’s possible VP pick are perfect time fillers. Grab two talking heads, some file footage from 2006 and an anchor can waste a solid ten minutes talking about whether or not Rice would “add anything to the ticket.” Nine times out of ten, it will probably work but the outcome is not inevitable. As Nathan Jurgenson has written before, “Campaigns can’t plan memes. Instead, the campaigns can merely react to them. Savvy staffers quickly jump in as a meme begins to go viral and try to capture the moment with an image.” Just as memes don’t go viral, sometimes no one cares about your deflection story. No single person, or even a single organization, can successfully and routinely control the entire discourse. Institutions like Fox News come close through sheer size, but once an idea is put “out there” the end result cannot be totally known.

The old saw “information wants to be free,” a relic of the early information society boosterism of Stewart Brand and Kevin Kelly, is no longer sufficient to describe the behavior of information flows and data patterns. The tendency of information to be free in both senses of the word—not restrained but also very cheap—is just one of many characteristics. When information is treated and sold as a commodity, it follows many of the same laws described by classical thinkers like Karl Marx and Pyotr Kropotkin. Information can be shared or exploited. It can be privatized for the good of the few or to amass capital for large projects; or it can be made public to aid in development of industries and the redistribution of wealth. Information does work and its exchange can result in material (not just semiotic) consequences. The tendency to make sweeping claims about the behavior of all information– from medical records to big bird memes– ignores the complexities of the social. Information is contingent, reactionary, and anarchistic.

Unlike most commodities, information has unpredictable properties: its value fluctuates wildly and who benefits from the transaction is never totally known until after the fact. Predicting what information will do, is like predicting the weather. You can predict possible outcomes, and the percentages of certain possibilities, but nothing is set in stone. Instead of looking at (mis)information as a tool of individuals, think of information as hiring the services of The Joker. You might unleash him, you might even have an agreement about what he is supposed to do (kill the Batman, naturally) but you are ultimately powerless to control the final result. In the case of the Romney campaign, their alternate reality was too tempting; an elaborate concoction of mythical independent voters and disaffected young Obama supporters that would come out to the polls in droves. Racist birther propaganda, woe-as-me stories about liberal media bias, and accusations that the labor department was fudging jobs reports all did exactly as they were supposed to do: convince people that Romney was the heir apparent. What they did not count on was how easily it would blind them and alienate others. John Dickerson of Slate writes,

How did the Romney team get it so wrong? According to those involved, it was a mix of believing anecdotes about party enthusiasm and an underestimation of their opponents’ talents. The Romney campaign thought Obama’s base had lost its affection for its candidate. They believed Obama would win only if he won over independent voters. So Romney focused on independents and the economy, which was their key issue.

It is not enough to say post-truth politics was a failed tactic. The more salient point to make is that it was a reckless strategy. The Obama campaign used similar tactics: deflecting bad press with meaningless stories, obfuscating their position on controversial issues, but the strategy was developed and deployed by Blue State Digital, one of the best online engagement planning firms in the US. Republicans on the other hand—as they are wont to do—went about extracting a resource without care for unintended consequences. The GOP drilled for fodder and meaningless spin like they were fracking for natural gas. Their plan might have worked, had they put more effort and resources into their social media and informatics teams. I am not making the case that only experts understand the internet, or that there is a certain superiority of the perspective taken by credentialed experts. I am merely saying that people who have a sophisticated understanding of how information travels (socially as well as technically) has a better chance of using information towards their own ends. Predicting how information will behave requires a lot of resources and cannot be treated as an afterthought. An organization as large and complex as a federal presidential campaign stands to gain by including many people with this expertise. It might mean the difference between a massive case of ineffectual groupthink and winning an election. For as long as that distinction matters (and it may not already), organizations will have devote their resoucres to the uncertain science of predicting what technology wants.

Comments 2

Austin — November 14, 2012

Stewart's full quote was, "On the one hand information wants to be expensive, because it's so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life. On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of getting it out is getting lower and lower all the time. So you have these two fighting against each other."

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_wants_to_be_free

I think that pretty well encompasses the tension you're describing and helps set up the point that Romney/the GOP over-commodified and undervalued it.

In Their Words » Cyborgology — November 18, 2012

[...] “the Internet lets us say more, but what we actually end up saying is more distracting than informati...” [...]