This post combines part 1 and part 2 of “Technocultures”. These posts are observations made during recent field work in the Ashanti region of Ghana, mostly in the city of Kumasi.

Part 1: Technology as Achievement and Corruption

The “digital divide” is a surprisingly durable concept. It has evolved through the years to describe a myriad of economic, social, and technical disparities at various scales across different socioeconomic demographics. Originally it described how people of lower socioeconomic status were unable to access digital networks as readily or easily as more privileged groups. This may have been true a decade ago, but that gap has gotten much smaller. Now authors are cooking up a “new digital divide” based on usage patterns. Forming and maintaining social networks and informal ties, an essential practices for those of limited means, is described as nothing more than shallow entertainment and a waste of time. The third kind of digital divide operates at a global scale; industrialized or “developed” nations have all the cool gadgets and the global south is devoid of all digital infrastructures (both social and technological). The artifacts of digital technology are not only absent, (so the myth goes) but the expertise necessary for fully utilizing these technologies is also nonexistent. Attempts at solving all three kinds of digital divides (especially the third one) usually take a deficit model approach.The deficit model assumes that there are “haves” and “have nots” of technology and expertise. The solution lies in directing more resources to the have nots, thereby remediating the digital disparity. While this is partially grounded in fact, and most attempts are very well-intended, the deficit model is largely wrong. Mobile phones (which are becoming more and more like mobile computers) have put the internet in the hands of millions of people who do not have access to a “full sized” computer. More importantly, computer science, new media literacy, and even the new aesthetic can be found throughout the world in contexts and arrangements that transcend or predate their western counterparts. Ghana is an excellent case study for challenging the common assumptions of technology’s relationship to culture (part 1) and problematizing the historical origins of computer science and the digital aesthetic (part 2).

Last Wednesday, our team attended the “enstoolment” (a ceremony similar to a coronation) of a local chief in the Ashanti region. Tons of people from all around dressed in their finest clothes and converged on the palace grounds to share in the festivities. Some wore traditional toga-like robes, while others dressed in polo shirts and slacks. The court sat on traditional stools, while most of the audience sat on plastic lawn chairs adorned with various Adinkra symbols. Black is the traditional color of formal events, which meant that when audience members took out their smartphones and tablets their lit screens shone like stars. Every few minutes, a new device emerged from underneath handwoven pieces of black cloth. The whole event challenges popular ideas about humans’ relationship to technology and what it does to our existing social habits. Just because there are cameras and internet connections does not mean people are disinclined to show up in person. An enstoolment is meant to happen in a particular place, with a bodily co-present audience. People still find the embodied ceremony meaningful, so they continue to show up and enjoy the ceremony. It is the same reason we still go to concerts even though we have plenty of recorded music- people like being around other people.

I am not trying to idealize or simplify the Ashanti culture, or the role of technology in our lives. Of course everyone doesn’t have a cell phone or an iPad. There are economic disparities in Ghana just like everywhere else in the world, and many people cannot afford a device that records video and puts it on the internet. Similarly, not every person at the enstooling ceremony was enraptured in the ecstatic wonder of ceremony. People made time for the enstoolment like you make time for a wedding or a city council meeting. Some people are more into it than others, some are tired, some were dragged there by a friend who is really into it, and a few felt obliged because their relative was a part of the ceremony. When we start thinking of “culture” as a distinct object, we begin to essentialize it: we turn it into a caricature of itself. An Ashanti businessman filming a royal ceremony with an iPad while dressed in traditional cloth might seem strange, novel, or even contradictory but such reactions are based in a reductionist logic. Culture is much more resilient and dynamic than something that can be dismantled by the very existence of an smartphone. As Clifford Geertz once wrote, “Culture is simply the ensemble of stories we tell ourselves about ourselves.” Those stories can be told in person, and they can be told via text message. The stories will change, and the culture will evolve, but it is up to those that self-identify as Ashanti (or whatever the culture may be) to decide what inventions are compatible with their culture. We heard that modernizing the facilities with indoor plumbing and asphalt roads was a major debate. I think it is safe to assume that there are strong opinions about smartphones as well. We might be tempted to assume that the royalty are the luddites, the keepers of the Old Ways, but one cannot ignore the modern sound system and surveillance cameras that were also installed and utilized.

Even if the have an introductory knowledge of anthropology, most people think of culture as a static object. There are common references in the media to national culture, sports culture, geek culture, online culture, pop culture, and urban culture. Main stream media outlets and popular nonfiction authors play fast and loose with the term, using it as a shorthand for any kind of shared practice, while also confining it to some kind of exorcized other. Culture is something you outgrow (youth culture) or something you visit (Their customs are so unique!) As my previous Geertz quote shows, anthropologists like to point out that our actions are always embedded in culture. From your birthday to how often you do your laundry, culture (perhaps more accurately: cultures) informs what you say and do. Raymond Williams, describes culture as simultaneously significant and mundane:

“We use the word culture in these two senses: to mean a whole way of life–the common meanings; to mean the arts and learning–the special processes of discovery and creative effort. Some writers reserve the word for one or other of these senses; I insist on both, and on the significance of their conjunction. The questions I ask about our culture are questions about deep personal meanings. Culture is ordinary, in every society and in every mind.”

Somehow, open definitions like Williams’ and Geertz’s have led many authors (claiming authority on the subject) to consider information technology as somehow apart from or even against culture. Culture, as the myth goes, is something established in the past and pushes against a constant barrage of modernizing and secularizing forces. We often think of culture as a paradox: on the one hand it is timeless, transcendent, and forms the bedrock of society. On the other it is fragile, easily sullied, and embattled. The former is utilized as a source of national pride, whereas the latter is often used to marginalize others. Technology is seen as the achievement of the strong culture (Technology as Achievement) and the corrupting influence of the weak (Technology as Corruption). Fascistic movements always appeal to the superiority of the national culture. It lasts because it is strong, and it is strong precisely because it can achieve great feats of technoscience. It trains athletes, fosters scientific pursuits, and wins great military victories. Eugenics campaigns were buoyed by the logic of Technology as Achievement. The movie “The Gods Must be Crazy” is an excellent example of Technology as Corruption. Produced and funded by South African apartheid supporters, the “Gods Must be Crazy” movies were made to convince audiences that racial segregation was meant to protect native populations from the corrupting influence of the modern nation state. South African tribes were depicted as child-like imps that lived in a world of natural mysticism. The most minor of intrusions -the existence of a coke bottle- would be enough to destroy their entire culture. Technology As Achievement and Technology as Corruption do not necessarily lead to fascism and apartheid but, taken to their logical extremes and popularly upheld, can justify the worst of atrocities.

Part 2: The Digital Boarderlands

In part 1 I opened with a run down of the different kinds of “digital divides” that dominate the public debate about low income access to technology. Digital divide rhetoric relies on a deficit model of connectivity. Everyone is compared against the richest of the rich western norm, and anything else is a hinderance. If you access Twitter via text message or rely on an internet cafe for regular internet access, your access is not considered different, unique, or efficient. Instead, these connections are marked as deficient and wanting. The influence of capitalist consumption might drive individuals to want nicer devices and faster connections, but who is to say faster, always on connections are the best connections? We should be looking for the benefits of accessing the net in public, or celebrating the creativity necessitated by brevity. In short, what kinds of digital connectivity are western writers totally blind to seeing? The digital divide has more to do with our definitions of the digital, than actual divides in access. What we recognize as digital informs our critiques of technology and extends beyond access concerns and into the realms of aesthetics, literature and society. I think it is safe to say that most readers of this blog think they know better: Fetishizing the real is for suckers. The New Aesthetic, a nascent artistic network, is all about crossing the boarder between the offline and the online. Pixelated paint jobs confuse computer scanners and malfunctioning label makers print code on Levis. The future isn’t rocket-powered, its pixelated. Just as the rocket-fueled future of the 50s was painstakingly crafted by cold warriors, the New Aesthetic of today is the product of a very particular worldview. The New Aesthetic needs to be situated within its global context and reconsidered as the product of just one kind of future.

I should start by saying that Bridle thinks “The New Aesthetic” is “a rubbish name.” Regardless of whether or not its a satisfying term, he must have originally chose it for a reason, and its probably the same reason that everyone else has embraced it as the moniker for all things de-resed, pixelated, and time-shifted. Its a straight-forward term that lets the reader know that it is not a movement, a school of thought, or an -ism. There’s no gate keeper that says what is or is not the New Aesthetic. The New Aesthetic is a consequence of a digitally augmented environment. You know the New Aesthetic when you see it. As Bruce Sterling says,

[T]he New Aesthetic is culturally agnostic. Most anybody with a net connection ought to be able to see the New Aesthetic transpiring in real time. It is British in origin (more specifically, it’s part and parcel of a region of London seething with creative atelier “tech houses”). However, it exists wherever there is satellite surveillance, locative mapping, smartphone photos, wifi coverage and Photoshop.

The New Aesthetic is comprehensible. It’s easier to perceive than, for instance, the “surrealism” of a fur-covered teacup. Your Mom could get it. It’s funny. It’s pop. It’s transgressive and punk. Parts of it are cute.

Perceiving an object as “The New Aesthetic” and making a piece of art in the style of The New Aesthetic are two totally separate things, but the differences are usually inconsequential. For example, I might look at a mannequin and see abstract cubes, not pixels:

Now, look at the weaving pattern of this traditional woven cloth, stamped with traditional symbols from the Ashanti region of Ghana:

Without getting too far into artist’s intent (and for my purposes, I don’t think I need to) let us consider the ambiguity of perception and intention. More specifically, why are we ready to see the pixels in the mannequin’s head, but not the cloth? The answer lies in something similar to a digital divide. Not an actual deficit of access, but a deficit in western perceptions of access.

The way we get online matters. It determines what “The Internet” means and what it looks like. At this year’s Theorizing the Web conference, I was on a panel with Dr. Katy Pearce who made a very convincing case for the “device divide.” (Slide show here.) Her work in Armenia showed that even when you control for age, socioeconomic status, and geography the device you use to connect to the internet has a powerful effect on what you do on the internet. The mobile internet may let you go on dating web sites and play games, but its much more difficult to work or create content through a mobile device. Ghanaians rely heavily on their mobile devices to get online, but they also rely on Internet Cafès. Ghanaians have internet access, but it doesn’t look like American internet access. Jenna Burrell describes Ghanian internet cafe use as,

…something akin to an arcade where they could chat with girls online (or offline) or watch American hip-hop and rap music videos. Most Internet users were using chat clients, especially Yahoo chat, or they were reading and writing e-mail in web-based applications like Hotmail. In interviews with users recruited from these Internet cafés, I was frequently told that they used the Internet to find foreign pen pals. The use of search engines and general web surfing activities were extremely uncom- mon. These online pursuits were often much more than a pleasant diversion and centered on improving their life circumstances by gaining powerful allies in foreign lands. (Burrell, 2010)

This sounds a lot like Pearce’s conclusions, although Armenians seem less interested in foreign pen pals. It is important to know what The Internet looks like to different people in different parts of the world, because an American or British New Aesthetic is going to look different than a Ghanian or an Armenian one. This information is necessary, but not always sufficient, which is why a global artistic network must include as many people, from as many cultures, as possible. Back in May, I (ironically) offered a few critical questions about the New Aesthetic (now numbered for ease of reference):

- What parts/aspects/facets of the digital are offered up as an ironic twist on out-moded technologies? In other words: Low res to whom?

- Where do we find the New Aesthetic? Where is the New Aesthetic conspicuously absent?

- What is its perspective? I see a lot of top-down.

- What technologies bring the New Aesthetic into existence? I see lots of military technology, big science, corporate logos, and agribusiness. What happens when we appropriate these artifacts and perspectives? What happens when we consume them? What happens when we prosume them?

- What parts of the digitally augmented world are left out, over-simplified, or left unquestioned? I see very little code.

- Is the pixel the sine qua non of the computer screen or does something else pre-date it?

- What is involved in the process of making things that embody the New Aesthetic?

- What is not the New Aesthetic?

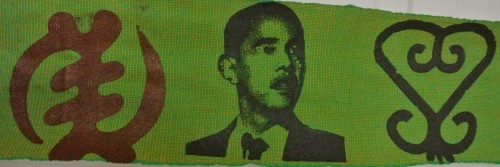

Contemporary anthropology and allied fields of study have spent the past thirty years challenging the technology/culture dichotomy, replacing it with a more fluid, dynamic, and adaptive depiction of both. From Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto to Jenna Burrell’s work on Ghanian internet cafès, anthropologists are bridging the rift between the cultural and the technological. Our work in Ghana, under the direction of Dr. Ron Eglash (a student of Haraway, and -for full disclosure- my academic advisor) sits firmly in this tradition. Our research group works on many different things throughout the month and, for the purposes of this essay, I will ignore my own work and make some brief comments on another group’s research on Adinkra stamping and Kente cloth weaving. They are developing browser-based math and computer science teaching tools based on weaving and stamping techniques. You can try the kente computing and adinkra grapher (and the rest of our culturally situated design tools) at csdt.rpi.edu.

Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education is usually taught ahistorically and outside of anything typically identified as “culture”. Two plus two equals four no matter where you were born, what god you believe in, or what kind of food you eat. The CSDTs are meant to introduce middle-school age students to math and science using real-world examples from various indigenous cultures. This goes beyond changing names in word problems (e.g. Jose and Maria trade apples, instead of Bob and Mary.) by actually demonstrating the implicit math and science that goes into these practices. For example, the trapezoidal Kente pattern below follows a very particular algorithm that produces predictable results:

With each new line the weaver must move a fixed number of strands towards the center. The vertical lines also follow a very specific pattern and width ratio. All of these patterns can be reproduced and expressed as functions. Our teaching tools allow students to program traditional and original Kente weaving patterns using a drag and drop user interface.

Certain Adinkra stamps follow very particular geometric curves. For example, the Gye-Nyame (meant to represent the supremacy of god and depicts a fist hold knives) has logarithmic spirals coming off the center “fist.” Adinkra symbols also rely heavily on the principles of transformational geometry: reflection, dilation, rotation, and translation.

The underlying math in these designs is important for the New Aesthetic because it forces us to reconsider our definitions of the digital. The Kente cloth is made line by line, just as your graphics card draws images on the monitor or your printer puts images to paper: line by line, dictated by a set algorithm. If/then statements, RGB values, and algorithmic patterns are all there, set in cloth by analog computers called looms. If this is not the New Aesthetic, images made tangible from the binary world, then we need a more precise definition of the New Aesthetic. Consider each cloth and pattern akin to the computer punch cards of the last century. These outputs produce an image that also tell a story. Its practically hypertext. One image calls up an entire proverb and an entire cloth can tell a story. Does it have to come from networked computers? Does it have to mimic or resemble something a 1990s computer-user from America would recognize? Do we have to assume that the artist has regular access to our kind of online experience? Let us explore one final example.

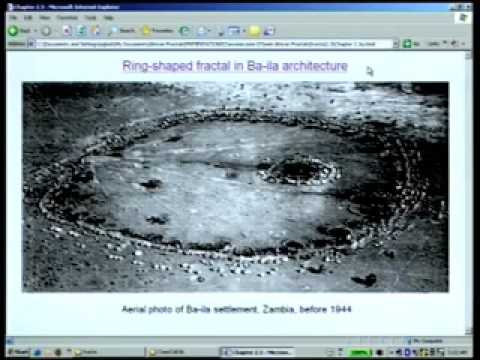

Back in 2007, Eglash gave a TED talk about African fractals. My favorite part (and the topic I will be discussing presently) starts at 10:50:

As Eglash describes in the video, Bamana sand divination relies on a sudo random number generator to produce a narrative about the future. This divination system was picked up by European alchemists and caught the interest of the German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz. Leibniz used the base 2 counting sequence to develop what we now call binary code. Every computer on earth is, in essence, a collection of mystics divining the future in the sand. It is precisely this historical lineage, that makes the “New Aesthetic” a very old concept indeed. As we draw our own lines in the sand, defining what is and is not the New Aesthetic we should consider our source material as the products of only one particular TechnoCulture. One that is pretty late to the game, if you are willing to count these 11th century geomancers as early forefathers of the computing age. If the New Aesthetic is truly about the intersectionality of the online and the offline, the digital made analog and back again, then we must decide what makes pixelated camouflage the New Aesthetic and not Kente weaving, Adkinkra stamping, or Bamana sand divination. If, while studying these boarderlands, we find that there is no discernable moment where the virtual was not substantiated in the sand, on cloth, or on display in a SoHo art gallery what becomes of the “New” of the New Aesthetic? If one concludes that these indigenous patterns are mathematical, even programable, but not the New Aesthetic, then we need a new definition that makes a more explicit case.

The pixelated future is being sold to us by Google and Facebook just like the rocket age was sold to the American public by a nation run by cold warriors. In its current form The New Aesthetic is anything but “culturally agnostic.” The future might go in the direction American entrepreneurs want it to, but let us make sure everyone can participate on their own terms. Let us make sure that everyone is included and given their due. If the future’s aesthetic is purely a product of the London art scene and Silicon Valley, I see little hope for the various progressive, metropolitan projects of the left. Instead, I see another imposed vision dictated by a select, elite few. The New Aesthetic has its roots in a global, multicultural effort that stretches from the sand of Egypt to the lofts of Austin, Texas. Without acknowledging either the privilege of the future’s aesthetic, or including the African and Middle Eastern roots (source code?) of our augmented world, we are blindly following another pied piper of mythical progress. The New Aesthetic is crowd-sourced and accessible to anyone, but lets situate our Western New Aesthetic within its global context. What kinds of New Aesthetic are we blind to, or do not recognize as such? Let us make sure that the aesthetic of the future includes everyone.

The research for this essay was supported by and was originally posted in RPI’s 3Helix Program funded by the National Science Foundation.

Comments 1

TechnoCultures | Post-Sapiens, les êtres technologiques | Scoop.it — October 23, 2012

[...] The “digital divide” is a surprisingly durable concept. It has evolved through the years to describe a myriad of economic, social, and technical disparities at various scales across different socioeconomic demographics. Originally it described how people of lower socioeconomic status were unable to access digital networks as readily or easily as more privileged groups. This may have been true a decade ago, but that gap has gotten much smaller. [...]