Unlike my fellow Cyborgologists, who are based in sociology departments, I am working towards a Ph.D in an interdisciplinary field called Science and Technology Studies (STS). The field emerged in the late 60s amongst (and directly influenced by) the environmental movement, the anti-nuke movement, and second wave feminism. Today STS is an established field with departments all around the world. The interdisciplinary nature of the field makes it difficult to have one single umbrella conference, but the closest we get is the annual Meeting of the Society for the Social Studies of Science, or simply “4S.” The conference has panels on a wide variety of topics including, “(Re)Inventing the Internet: New Forms of Agency“, “Evidence on Trial: Experts, Judges and Public Reason“, and “Reproductive and Contraceptive Technologies: Shifting Subjectivities and Contemporary Lives“. There are also two sister conferences that happen simultaneously at nearby hotels: The Society for the History of Technology (SHOT) and the History of Science Society (HSS). While the conference was enjoyable, and the talks were fascinating, I was left wondering if STS is up to the task of changing how we talk about technology, science, and innovation.

There is a lot to talk about, but I want to focus on a meta-level critique that I saw throughout the conference. Now, more than ever, it seems as though the insights of STS scholars are crucial to the major events of the day. Unfortunately, our work has not reached popular press, nor has it had a major influence on socio-technical policy. As I have argued elsewhere, STS has done a poor job of making its canon relevant to the times. This is part of a larger problem that Nathan identified, that of the Internet Anti-Intellectual. While business leaders have been busy churning out popular press books by the dozens, scholars of technology and science are caught up talking amongst themselves in expensive journals and dense books. The question remains: How do scholars gain control of the conversation on technology’s role in society? I posed this question to E. Gabriella Coleman after her presentation in “STS 2.0: Taking the Canon Digital”. Her response was rather straightforward, scholars need to get into op-ed columns. We need to start writing for popular audiences in a big way. We also need to start experimenting with new forms of publication. She then reiterated a strong statement from her presentation: “We need to end the monopoly of the cultural pundit.” I think we at Cyborgology are ahead of the curve on this mission. Our overall project has been one of mainstreaming academic work by providing relatively short, readable, and (dare I say it) entertaining posts about science, technology, and society. Most bloggers would not say this, but speaking personally- I want more competition! I want more popular texts in the field of society and technology.

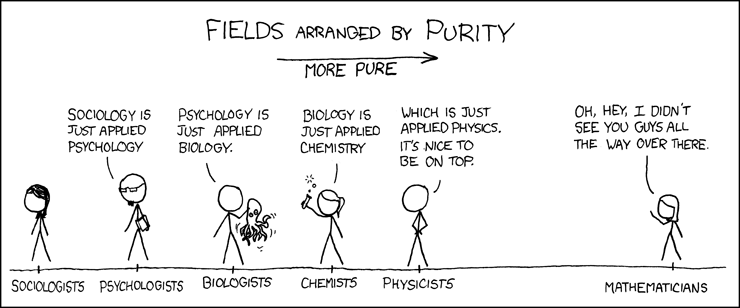

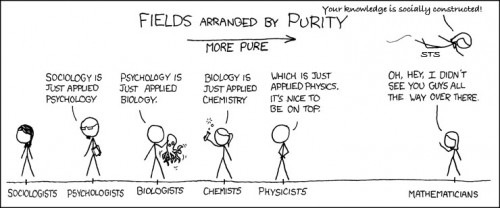

I’d like to end here with an XKCD comic that Dr. Coleman put in her presentation, to demonstrate social science’s relationship to science and technology in the popular imagination:

Randall Monroe’s depiction of sociology as somehow “impure” speaks to the popular concepts of objectivity and subjectivity. The natural sciences are objective windows on how the world works, and the social sciences sit atop these truths on a bed of subjective opinions and observations. Sociology cannot penetrate these core layers of meaning, or provide insights on how mathematics (for example) is the product of a social activity called knowledge production. In short, STS (and my own work on Cyborgology) have been trying to make one, very basic, statement:

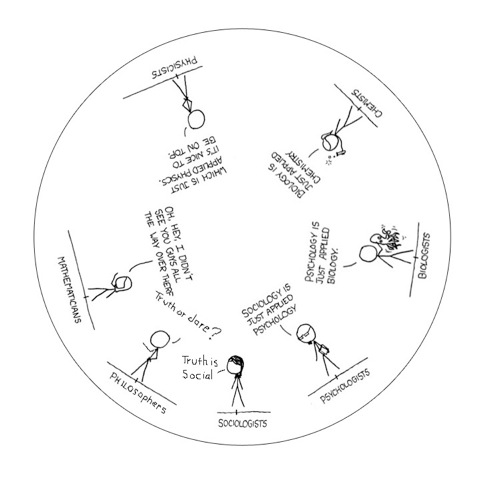

EDIT: November 07, 2011 19:04 EST- I made that STS reply cartoon back in April, and my advisor, Ron Eglash had replied to me in kind. With his permission I am including it below:

Comments 8

Ben Brucato — November 7, 2011

In STS -- as well as in cultural studies, lit crit, and the full host of contemporary interdisciplinary fields overarching the humanities and social sciences -- we have developed a language and conceptual toolbox (or maybe I would prefer "knapsack" as a metaphor if only to suggest its need to be unpacked) that are foreign to most undergraduates in our own field, let alone accessible to broader publics. These have provided a linguistic turn for the medieval institutions we inhabit: along with the organizational and social systems of vetting, the rigors of filling out our transcripts, the academic hazing of the dissertation processes, and so on, we now add a hyperspecialized initiatory language that surpasses any Hermetic order. And this is before we enter our field as credentialed experts! Our texts require the degree of translation typical of an alchemist's notebook to make literate a public reader, and much of the ideas contained would bear little relevance. Perhaps we need not concern ourselves with throwing the pearls to the swine or teaching them how to convert lead to gold. Instead we might endeavor to challenge the value of gold in the first place.

Ron Eglash — November 7, 2011

This reminds me of the time I was a UCLA undergrad spending a semester at the Catalina Island Marine Biology institute. One day we hiked to the far side of the island to look at the high-impact tidal zone. We at lunch on some rocks, and my friend said "you know I was thinking we are just like a troop of baboons or chimps sitting on a beach; just a different species of primate." I had been eating on top a high boulder, so I said "not me, I was an anthropologist studying the troop." And my friend replied "yeah well every time they study a troop of chimps who are having fun eating and playing and having sex there is always that one chimp off to the side banging his head against a rock."

So while the cartoon could be read as "STS is above it all" I think the image of STS as the one chimp banging its head against the wall is also good to keep in mind. I hate the hubris, arrogance, and elitism that "meta-analysis" invites. Anything we can do to keep those attitudes at bay is a good counter-balance.

I know the up-manship game can be played in both directions; its easy to put down philosophy or social science as "just talk." But my guess is that *within* STS we need more effort on helping our discipline move towards a more collaborative stance. For a longer rant on the subject see http://homepages.rpi.edu/~eglash/eglash.dir/SSS/technophilia.pdf

Gareth Edel — November 7, 2011

I agree there needs to be more and better conversation among and between groups about the roles and effects of science and technology in society

But as an alternative, I feel that trying to take STS research into other disciplines like communications, science writing, and education is in some ways a more useful step than making us all go directly to the public. I wonder if (inspired by the comic strip) your applying unfair demands on an academic discipline such as STS. If we are like physicists - perhaps we should be like physicists. Physicists rarely have to be both researchers and popularizers, and while Brian Green and others do manage it, they are not average. Perhaps a more fair statement would at least give credit for the demand that more STS practitioners double up on job description. I'm just saying, as a phd candidate, I'm interested in teaching, and research, and may even try to write for a popular audience, but when was the last time you insisted that a research physicist do better at communicating and participating in public discourse? I don't see a distinction between the social and natural sciences in the role of the "Scientist". Whole seperated disciplines are at work putting out material into the culture to free the "scientist" from the burden of distraction from research, I'd say that they would do well to participate in public discourse, at very least as a mechanism to increasing the volume of discussions if not the quality.

For example, "Science Education" as a practice and as a specialized domain of educators and a separate academic field of research, popular science writers and science writing programs, science communications programs and scholars, all should be in conversation with both the public and research scientists - perhaps you'd do better convincing them to take social sciences approaches to science seriously as an important step to bringing STS to the world, rather than solely by making STS scholars step into the gap that their fields are already designed to fill.

That said, I kept in mind as I chose my dissertation research that I wanted a topic around which i would potentially be able to bring conversation into the public sphere. I have tried going to communications and other conferences outside my discipline, and I admit I'm not doing enough, but I hope that we can talk about institutional responses to broaden public discourse without simply saying researchers need to also be popularizers, both are valuable, and challenging enough on their own. We can't all be Stephen J Gould.

Sal Restivot — November 8, 2011

One of the problems with 4S members is that after almost 40 years people aren't focused enough on their field to know that we are the Society for Social Studies of Science, NOT the Society for THE social studies of science. The late David Edge and I had to point this out repeatedly to our colleagues, and here the mistake appears again; and it appeared again recently when someone started a 4S group on Linkedin. I hope I don't have to explain why this is important. It is symptomatic of a field in which newcomers fail to commit themselves fully to S&TS as their field of inquiry and have only vague and often mistaken ideas about the field and its social and political impacts. 4S members, including this commentator, have been involved in changing the nature, structure, and policies of the National Science Foundation, the National Academies, multicultural educational initiatives around the world, AAAS, the science and technology arms of the U.S. Congress (notably, we were active in the development of the Office of Technology Assessment; we could not keep it operational, however, in the face of political - primarily Republican - resistance). Many of us have been consultants to national science policy groups around the world throughout the entire history of 4S and S&TS. There are many links from S&TS to social change that are unfortunately but perhaps necessarily part of the informal, shadow part of the organization of the field. Regarding the origins of the field and the society, there is a general awareness of the 1960s context but not enough attention to the roles of the Radical Science Movement and the Science for the People movement. And the earliest meetings were well attended by leading science policy agents, notably from eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. None of this is to deny the validity of some of the "complaints" registered here. Since its beginnings, STS has undergone numerous modifications and reincarnations, yet the initial work stands as an early articulation of its continuing provocative potential. We need to understand the dynamics whereby the “disobedience” fostered by STS can flourish and persist ( STEVE WOOLGAR, 4S founding member and Bernal Prize receipient, 2004). Yours, Sal Restivo (4S founding member and former president) and the ghost of David Edge (4S founding member, former president,and Bernal Prize recipient).

Cyborgology Weekly Roundup » Cyborgology — November 13, 2011

[...] David Banks reflected on the recent Society for the Social Studies of Science meetings in Cleveland [...]

Technoscience As Activism Conference » Cyborgology — February 29, 2012

[...] after attending the annual meeting for the Society for Social Studies of Science (4S), I posted a critique of the traditional conference format. I was frustrated with the apparent hypocrisy of expensive, closed-door conferences full of [...]