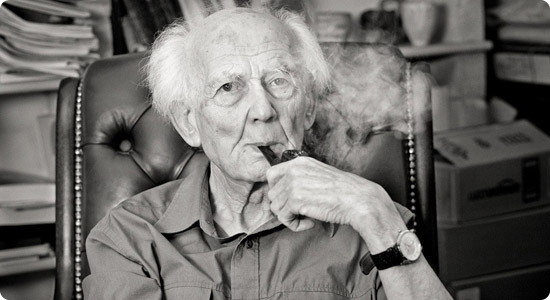

Zygmunt Bauman has famously conceptualized modern society as increasingly “liquid.” Information, objects, people and even places can more easily flow around time and space. Old “solid” structures are melting away in favor of faster and more nimble fluids. I’ve previously described how capitalism in the West has become more liquid by moving out of “solid” brick-and-mortar factories making “heavy” manufacturing goods and into a lighter, perhaps even “weightless,” form of capitalism surrounding informational products. The point of this post is that as information becomes increasingly liquid, it leaks.

Zygmunt Bauman has famously conceptualized modern society as increasingly “liquid.” Information, objects, people and even places can more easily flow around time and space. Old “solid” structures are melting away in favor of faster and more nimble fluids. I’ve previously described how capitalism in the West has become more liquid by moving out of “solid” brick-and-mortar factories making “heavy” manufacturing goods and into a lighter, perhaps even “weightless,” form of capitalism surrounding informational products. The point of this post is that as information becomes increasingly liquid, it leaks.

WikiLeaks is a prime example of this. Note that the logo is literally a liquid world. While the leaking of classified documents is not new (think: the Pentagon Papers), the magnitude of what is being released is unprecedented. The leaked war-logs from Afghanistan and Iraq proved to be shocking. The most current leaks surround US diplomacy. We learned that the Saudi’s favored bombing Iran, China seems to be turning on North Korea, the Pentagon targeted refugee camps for bombing and so on. And none of this would have happened without the great liquefiers: digitality and Internet.

These technologies create information that is more liquid and leak-able and have also allowed WikiLeaks to become highly liquid itself. It is not just one website, but also flows throughout the web on its many “mirror” sites. The data is disseminated over peer-to-peer (P2P) networks making it truly “the new Napster.” And just as shutting down Napster did not end music-sharing, shutting down WikiLeaks will not end the sharing of classified information.

But what are the consequences of this new politics of liquidity?

The early days of the public Internet saw the emergence of a “hacker” culture that eventually turned more explicitly political from the 1980’s through the 90’s into what has come to be known as “cyberlibertarianism.” What defines this movement is the belief that information should be free, a stance clearly shared by WikiLeaks renegade editor-in-chief, Julian Assange (who is on the cover of the next Time magazine).

Assange’s goal is to end government secrecy. And he acknowledges that the government response to WikiLeaks will be to become more secret. And that, perhaps counter-intuitively, is exactly the point. As Assange states (via),

in a world where leaking is easy, secretive or unjust systems are nonlinearly hit relative to open, just systems

This argument made by Assange is similar to an argument made by George Ritzer. Using Bauman’s terms, Ritzer argues that old, heavy structures need to become more porous else they will be washed away in the wave of liquidity. Assange’s strategy is exactly to make the U.S. government more secretive and therefore less porous. Thus, the government will be less effective at communicating both internally and diplomatically with others – what Assange calls the “secrecy tax.”

This argument made by Assange is similar to an argument made by George Ritzer. Using Bauman’s terms, Ritzer argues that old, heavy structures need to become more porous else they will be washed away in the wave of liquidity. Assange’s strategy is exactly to make the U.S. government more secretive and therefore less porous. Thus, the government will be less effective at communicating both internally and diplomatically with others – what Assange calls the “secrecy tax.”

The history of the Internet will be, in part, its role in creating an increasingly liquid world, and WikiLeaks will come to be as important (or more) than Napster in this regard. Aside from if one is for or against WikiLeaks, we should ask: Is Bauman correct? Will the U.S. government come to be harmed by becoming increasingly solid, heavy and out-of-date in the face of the modern torrent of liquidity?

Comments 8

El mundo según Wikileaks – elmorsa.pe — December 9, 2010

[...] por la separación entre la esfera pública y la esfera privada. Nuevamente queda en evidencia que esa separación está en discusión. ¿Es de interés público conocer los chismes diplomáticos? En los tiempos de la larga cola, todo [...]

Jenny Davis — December 9, 2010

Just read this article this morning. We are now being asked to police ourselves in the face of liquid culture. Can Foucault apply in a liquid modern world?

http://www.cnn.com/2010/CRIME/12/08/wikileaks.students/index.html?hpt=T1

e-book-news.de » Welt im Fluss: WikiLeaks und unsere verflüssigte Moderne — January 8, 2011

[...] & CC-Lizenz: Nathan Jurgenson Übersetzung: Ansgar Warner (Originaltitel „WikiLeaks and our Liquid Modernity“, erschienen auf Cyborgology @ [...]

Educating the journo-programmer « UNBERKELEY — January 24, 2011

[...] reference earlier works. This came up in a Twitter exchange, where calixte said that WikiLeaks had liquified the press, turning it into a river. I love that. I think it’s very true. Assange basically [...]

Dave Winer: How can universities educate journo-programmers? » Nieman Journalism Lab » Pushing to the Future of Journalism — January 24, 2011

[...] reference earlier works. This came up in a Twitter exchange, where calixte said that WikiLeaks had liquified the press, turning it into a river. I love that. I think it’s very true. Assange basically [...]

Egypt’s Liquid Modernity « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n — March 22, 2011

[...] that I find infinitely useful for thinking about the Internet. My previous post on Wikileaks and our Liquid Modernity outlins how the Internet and digitality are making information more fluid, nimble and difficult to [...]

Egypt’s Liquid Modernity » Article » OWNI.eu, Digital Journalism — March 25, 2011

[...] that I find infinitely useful for thinking about the Internet. My previous post on Wikileaks and our Liquid Modernity outlins how the Internet and digitality are making information more fluid, nimble and difficult to [...]

A New Paradigm of Leaking: Anonymous’ “Delicious Data” « PJ Rey's Sociology Blog Feed — September 28, 2011

[...] Ellsberg‘s famous leak of the Pentagon Papers). Anonymous is demonstrating, however, that in the highly liquid world of digital information, leaks no longer need to be pushed from within, but can be pulled from without. That is to say, [...]