I have been thinking through ideas on this blog for my dissertation project about how we document ourselves on social media. I recently posted some thoughts on rethinking privacy and publicity and I posted an earlier long essay on the rise of faux-vintage Hipstamatic and Instagram photos. There, I discussed the “camera eye” as a metaphor for how we are being trained to view our present as always its potential documentation in the form of a tweet, photo, status update, etc. (what I call “documentary vision”). The photographer knows well that after taking many pictures one’s eye becomes like the viewfinder: always viewing the world through the logic of the camera mechanism via framing, lighting, depth of field, focus, movement and so on. Even without the camera in hand the world becomes transformed into the status of the potential-photograph. And with social media we have become like the photographer: our brains always looking for moments where the ephemeral blur of lived experience might best be translated into its documented form.

I have been thinking through ideas on this blog for my dissertation project about how we document ourselves on social media. I recently posted some thoughts on rethinking privacy and publicity and I posted an earlier long essay on the rise of faux-vintage Hipstamatic and Instagram photos. There, I discussed the “camera eye” as a metaphor for how we are being trained to view our present as always its potential documentation in the form of a tweet, photo, status update, etc. (what I call “documentary vision”). The photographer knows well that after taking many pictures one’s eye becomes like the viewfinder: always viewing the world through the logic of the camera mechanism via framing, lighting, depth of field, focus, movement and so on. Even without the camera in hand the world becomes transformed into the status of the potential-photograph. And with social media we have become like the photographer: our brains always looking for moments where the ephemeral blur of lived experience might best be translated into its documented form.

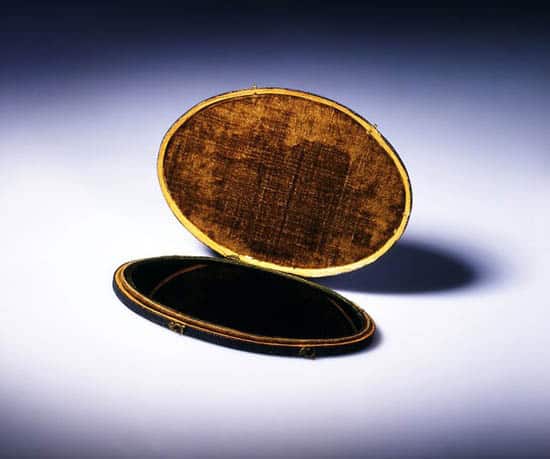

I would like to expand on this point by going back a little further in the history of documentation technologies to the 17th century Claude glass (pictured above) to provide insight into how we position ourselves to the world around us in the age of social media.

Do I have to make the case that self-documentation has expanded with social media? As I type this in a local bar, I know that I can “check-in” on Foursquare, tweet a funny one-liner just overheard, post a quick status update on Facebook letting everyone know that I am working from a bar, snap an interesting photo (or video) of my drink and this glowing screen, and, while I’m at it, write a short review of the place on Yelp. And I can do all of this on my phone in a matter of minutes.

While self-documentation is nothing new, the level and ubiquity of documentation possibilities afforded by social media, as well as the normalcy to which we engage in them, surely is. And, most importantly, sites like Facebook, for the first time, guarantee an audience. Thus, social media provides both the opportunity and motivation to self-document as never before.

What does any of this have to do with the Claude glass, a little-known 17th century mirror-device?

The Claude glass is (usually) a small (usually) convex mirror that is (usually) the color grey (the darkened color gave it the nickname “black mirror”). The device assisted 17th and 18th century “picturesque” landscape painters, especially those attempting to emulate the popular paintings of Claude Lorrain (whom the device is named after). By standing with their back to the landscape and towards the Claude glass mirror, the viewer is provided with a mirror-image of the landscape behind them. The mirror’s convex shape pushes more scenery into a single focal point in the reflection (which was considered aesthetically pleasing in the “picturesque” genre). And the grey-smoke coloring of the lens changes the tones of the reflection to those that are more easily reproduced with the limited color palette painters employ.

The Claude glass also came to be used by more than painters. Wealthy English vacationers took countryside vacations in search of “picturesque”-style landscapes reminiscent of the famous paintings. These tourists would often carry a Claude glass in their pocket so that they could turn around and view the world, slightly convexed and re-colored, as if it were a painting. Often, they would also use the device to make a sketch, wanting to return home with some documentation of the beauty witnessed on vacation. Competent in what is picturesque, the wealthy demonstrated their “superior” cultured taste distinct from lower and middle classes as well as the new rich. This trend is well documented in the book, The Claude Glass: Use and Meaning of the Black Mirror in Western Art by Arnaud Maillet (2004).

The term “picturesque” as the name for this trend is important to clarify. It refers to what which is worthy of emulation and documentation; to resemble or be suitable for a picture (which, in the 17th and 18th centuries meant a painting). Importantly, that which is “picturesque” is typically associated with beauty, even though many scenes worthy of pictoral documentation are not necessarily beautiful (a horrific war-scene, for instance). Thus, the Claude glass was sort-of like the Hipstamatic or Instagram of its day: it presented lived reality as more beautiful and already in its documented form (be it a painting or a faux-vintage photograph). Indeed, there are similarities in style between Claude Lorrain’s paintings, the images seen in the Claude glass and the effects that the faux-vintage photo filters employ.

Digitally Picturesque

The Claude glass presents us with an image of the tourist standing exactly away from that which they have traveled to see. Instead, the favored vantage-point is of reality already as an idealized documentation. Both the Claude glass and the Hipstamatic photo present this type of so-called nostalgia for the present. I think this a useful metaphor for how we self-document on social media. Let’s split this parallel between the Claude glass and Facebook into three separate points:

First, the Clade glass metaphor jives with the notion of the “camera eye” that I have used previously. They are both examples of what I call “documentary vision,” that is, the habit of viewing reality in the present as always a potential document (often to be posted across social media). We are like the 18th century tourist in that we search for the “picturesque” in our world to demonstrate that we are living a life worthy of documentation; be it literally in a picture, or in a tweet, status update, etc.

Second, the Claude glass model presents the Facebook user as turned away from the lived experience that they are diligently documenting, opposed to the “camera eye” metaphor of facing forward towards reality. One worry surrounding social media is that our fixation on documenting our lives might hinder our ability to live in the moment. Do those fixated on shooting photos and video of a concert miss out on the live performance to some degree? Do those who travel with a camera constantly in-hand sacrifice experiencing the new locale in the here-and-now? Does our increasing fixation with self-documentation position us, like the Claude glass user, precisely away from the lived experience we are documenting?

Third, the Claude glass is affiliated with the “picturesque” movement that equated beauty with being worthy of pictoral representation. The Claude glass model would describe our use of social media as the attempt to present our lives as more beautiful and interesting than they really are (a reality we have turned our backs on). When our reality is too banal we might reshape the image of ourselves just a bit to make our Friday night seem a bit more exciting, our insights more witty, or homes to be better furnished, the food we cook more delicious, our film selections more exotic, our pets more adorable and so on (which creates what Jenna Wortham calls “the fear of missing out”).

To conclude, these last two points demonstrate how the model of Claude glass self-documentation on social media differs from “the camera eye.” Both the camera and the Claude glass share the effect of developing a view of the world as one of constant potential documentation. The difference is that the Claude glass metaphor presents the social media user as turned away from lived experience in order to present it as more picturesque than it really is. Thus, the questions I am still working on and those I would like to pose to you become: Does this capture the reality of the Facebook user? Are we missing out on reality as we attempt to document it? Are we portraying ourselves and lives as better than they actually are?

Header image source: http://carterseddon.com/claude1.html

Comments 36

Chris — July 25, 2011

If we accept that we constitute ourselves largely through the stories we tell each other, then we also have to accept that we've always portrayed our lives as better (in the broadest sense encompassing whatever value or ideal we skew towards) than they really are. For me the Claude glass metaphor has its greatest utility in the way it captures simultaneity and multi-media: I'm no longer embellishing stories about my past with words, I'm embellishing stories about my present- or near-present, the virtual projection of my present- with videos, pictures, maps, and words. When you combine all of these sensory media with simultaneity of the event and its documentation, the medium forces an improvement of the object. You say that the photographer sees the world differently through constant, simultaneous awareness of its photographic aesthetics-- is it possible that the self-conscious, simultaneous self-projector (social media addict) sees the world in the same way? Would she/he not only seek out experiences that are commonly recognized by her/his community as somehow actually "better" (ie go to a concert instead of watch tv), but also be able to have objectively "better" experiences than the person standing next to him/her (ie have more fun at a concert than otherwise)? Does a photographer actually see more beauty in the world than a non-photographer? If so, could we then say that the social media addict actually has a better life, a better reality, as a result of the all-encompassing aesthetic lens of social media?

Jenny Davis — July 26, 2011

You ask: "Are we missing out on reality as we attempt to document it? Are we portraying ourselves and lives as better than they actually are?"

These are two questions which have, I think, two very different answers.

In the case of the former, I say no. We are not missing out on the reality that we work to document. Documentation becomes part of the experience, not a replacement for the experience.

In the case of the latter, however, I would say yes. Of course we portray our lives as better than they are...or at least ourselves as more witty than we are.

The camera and Claude-glass metaphors need not be mutually exclusive. We think about everyday experience in terms of ideal documentation (camera style), and sometimes intentionally reconstruct these experiences via social media (Claude-glass style). The people who used Claude-glass likely did not ignore the natural scenery completely, but enjoyed the scenery in multiple forms. Claude-glass did not make the experience less real. Rather, like a tweet about a bar fight you just lost, it becomes another aspect of the experience.

nathanjurgenson — July 26, 2011

jenny, good comments!

let me put aside the issue of beautifying our lives for a moment and focus on your point that one can document without losing anything. i do realize that the Claude glass user as well as the modern social-media-photographer do put away their devices. i only use the Claude glass user, turned away from the world, as a metaphor for the idea that when documenting experience, we might be losing, or turning away, from something.

when traveling on vacation i know i have a different experience when i am holding a camera versus not. many people have told me the same. in fact, some have explicitly told me they had to make themselves NOT bring a camera in order to more fully enjoy the traveling experience. do you not agree with this?

i do think that something is lost when focusing on documentation. however, what i have not done yet is really explain what that is. i also have not explained what might be *gained* by focusing on documentation.

Jenny Davis — July 26, 2011

I do agree that something CHANGES when documenting, but I'm not convinced yet that something is lost.

Certainly you would want to leave the camera at home to have a certain kind of travel experience, but whether it is a more or less fulfilling experience, to me, is an open question.

I guess I'm also a bit wary of considering documentation a form of "turning away." It seems as though documentation, when done in moderation, can be rolled in to the experience, rather than thought of as something outside of the experience. I do agree, however, that it is problematic when the need to document overtakes (rather than supplements/augments) the experience. This is perhaps a pathological manifestation of documentation.

Stephanie Medley-Rath — July 27, 2011

I think that those who seek to self-document can become more observant of their life. In this way, I think they are getting as much if not more out of the experience, than those not doing any additional documenting. I study scrapbookers (and I am a scrapbooker) and if they do not have a camera or do not take a photo, it is usually purposeful. Part of leaving a camera in its bag has to do with its bulkiness and obtrusiveness. With my iPod touch, I can take a photo rather discretely. No one knows that I just took a photo with my instagr.am app of my laptop and chai in this coffee shop except those reading this comment and those that see my photo. My guess is that we are going to see even more documentation due to these technologies. They are more convenient for the purposeful self-documenter and people who would otherwise not document something, now are always carrying around the tools to do so if the mood strikes. This week, Ali Edwards (a thought leader among scrapbookers) is leading A Week in the Life [http://aliedwards.com/projects/week-in-the-life]project among her blog readers. I’m not sure how many people participate, but it is in the hundreds, most likely thousands—thousands of people documenting this one week and creating a scrapbook about it. They are taking photos, committing memories to paper or their blogs, saving receipts and other paper memorabilia from this one week. I’m already thinking of the research projects I could take with this one subculture among scrapbookers. I’m participating in the “movement/event/whatever you want to call it” for the first time to see what observations I can make as a participant instead of just an observer.

Now your second question, yes and no. I think the possibility is there to focus on the positive, but I think there are plenty of folks focusing on the negative. Based on my own facebook newsfeed, I see posts from a grieving mom who lost her son last year. I see posts from stay-at-home-moms who are frazzled and talk about the mundane things in their life (diaper changes, new bunk beds, children who won’t sleep, and so on). I see posts from colleagues commenting on their students’ work habits and reactions to course content. Among scrapbookers and bloggers who are also scrapbookers, I would say they make a point to show the negative, too. In my study, my respondents said they would scrapbook the negative. One scrapbooker scrapbooked her miscarriage, another scrapbooked her mother’s funeral, while another scrapbooked the death of her daughter’s best friend. Other negative things become reframed in positive terms. It’s not a death, but a celebration of life, for instance. Sometimes the very absence of the negative is a way of preserving the negative. In my own scrapbooks, there are several years memorialized without any photos of one family member or another. I don’t need a page telling me why they are not in the scrapbook. I know why they aren’t there. The other issue about memorializing the negative has to do with social norms surrounding the negative. If I get in a fight with my friend, I don’t say, hang on a minute while I photograph this moment. If we are having fun, I can say hang on a minute while I take a picture.

I feel like I am rambling at this point, but one other thing to keep in mind is the issue of social class. It seems that smart phones are everywhere, but they really aren’t. This point became clear when I went to the carnival in my small town a few weeks ago. The ride operators all had cell phones (basic flip phones, not sliding keyboards), but none of them had smart phones. They may have had cameras on these phones, but they were not connecting to the internet very easily if at all with these phones. (I suppose, they could be texting status updates.) Cameras are more accessible than they ever have been, but there is still a digital divide between who can share their self-documentation with the world wide web and who can’t.

Chris Baraniuk — July 27, 2011

I couldn't agree more with Jenny! I would go slightly further, indeed, and say that documentation doesn't just "become an aspect of experience" - I wonder if at the moment of documentation, documentation IS the experience. I wonder if human beings have any conscious methods of being in the world which aren't documentary.

Memory itself is a famously selective, multi-faceted documentation machine. There is something rigidly finite about extrapolating mere memory into poetic, portable devices like the Claude glass, however. Well done to Nathan for picking up on such a beautiful object. Refracting light, re-colouring it, cropping appropriately... and the exquisite fact of having to literally turn one's back on the scene in order to view an idealised version of it... This emphasises the mediated nature of all documentary activity and is so close to the experience we have today of watching tourists supposedly 'blindly' snapping their way through famous cities, places of natural beauty and historic cities, functioning only with camera in front of their faces.

Jenny Davis — July 28, 2011

Nathn (and Chris)I want to point out that I think the Claude glass is a really helpful and insightful metaphor. I also think that the expectation of documentation, as you say, necessarily changes the experience. I even think, as I said in my very first post here, that the expectation of documentation influences heavily the lines of action that we take.

The only thing I think we should be careful about is the value judgment--to say that documentation is a "turning away" from experience can quickly fall into the trap of digital dualism.

I think, as you say in your response above, that the interesting point of analysis here is the *worry* that we are losing something due to documentation. I think that worry is ripe for analysis, but I don't think we are in a position to determine whether or not (or to what extent) the worrying is justified. I would be interested to know how people responded to the claude glass...did the same type of worry persist?

David Zweig — July 29, 2011

Nathan,

This is a terrific post. The distinction you draw between the camera eye and the CG is astute.

As you can imagine, for my book on Fiction Depersonalization Syndrome I've been deep into researching how our devices/media/technology affect how we interact with each other and nature, so this was a fun post for me read. The examples were familiar, though you framed them in a compelling way. One person not mentioned yet here, who perhaps should be, is Sontag. "On Photography" covers some of the "camera eye" and documentation issue brought up in the post and the comments.

Separately - using the word "reality" creates a pretty dicey semantic problem. Anything we experience, is reality of course. I tend to think and describe the difference as "direct" experience versus "indirect" or "mediated" experience, rather than saying one is real or not.

"We are not missing out on the reality that we work to document. Documentation becomes part of the experience, not a replacement for the experience." Jenny, Chris - the way I see it, since documentation does become part of the experience, then the experience itself is altered, meaning it IS in effect, replaced by something else - this new, altered, "hybrid" experience.

"I do agree that something CHANGES when documenting, but I’m not convinced yet that something is lost." How can something not be lost when something is changed? Something new is gained of course too, but when something is gained, something must be lost. Whether that loss and gain are balanced or tilted favorably one way or the other is a separate question. Which leads me to: it seems that academics have a default position to shy away from value judgments; I understand the importance of that position. Yet, it's also ok at times, if not essential, to make value judgments, or at least hypotheses or guesses about value. Some degree of documentation is healthy - humans have been doing it in one way or another forever. But, I'd argue that for many people, excessive attention to documenting experience not only changes the experience (as you indicated) but in some way, ultimately, may lessen certain experiences, and in a broad way, one's overall life. Every major religion talks about the value of being present or "in the moment." My own research shows that people tend to have higher degrees of depersonalization and/or unwanted self-conscious feelings when they spend too much* time observing, rather than directly "living." Again, I'm not saying documentation is bad across the board; it's when that tendency is excessive that experience, over all, for many, is lessened in some way.

*How much is too much is another question!

Rob — July 29, 2011

Think the reflexivity involved in self-documentation certainly affects experience and is not the true content of all human experience. Also think digital culture has encouraged the idea that documentation is the only human telos

Xavier Matos — July 31, 2011

Great post, loved the metaphor; even greater discussion in the posts, this blog is great :)

Although I don't think anything is necessarily lost, as Jenny said, I definitely find myself often chastising people in my mind for not putting down their cameras, never mind their phones. Two small examples of this:

1 - I was at a concert not too long ago. At the beginning of the concert, many people, my brother included, brought out their phones to document the climatic entrance of the main performer, and I think this was perfectly understandable. However some people literally had their cameras raised for 80% of the concert, and I refuse to believe they weren't missing out on the experience.

2 - I have a friend with whom I now refuse to watch movies I care for. This is because he finds it entirely unreasonable to ignore his phone for the duration of two hours, and he was mostly just texting, not taking important phone calls or anything. I believe that a dramatic narrative will not have the same impact when your mood and focus are constantly being affected by the persistent injection of social media and mass communication

David Zweig — August 1, 2011

@Xavier

Totally hear you re both your examples. Re #2 - this is the myth of multi-tasking. You can watch a movie and do your email and read a magazine at the same time, but you're not really watching the movie. Multi-tasking is largely an illusion. If you're the kind of person who's happy kinda of doing stuff then multi-tasking is for you; if you're the kind of person who likes to be completely focused and immersed in what you're doing/or whom you're talking with then multi-tasking simply has no place in that scenario.

David Zweig — August 1, 2011

oops - forgot to close the ital html.

Replqwtil — August 20, 2011

I think an idea that I would relate to this, and which I saw mentioned or skirted around several times throughout the comments, is that of Transparency in the mediums. Talking about mediated or unmediated experiences is a bit of a herring, when I think that All reality is mediated. If the only access to Reality for our consciousness passes necessarily through mediums, then the important difference is the level to which that medium impresses itself on that experience. Wich is to say to what degree it is obvious to us that we are using a medium at all.

Obviously our own body and senses are the archetypal medium for most of us, the most transparent and by which all other mediums are accessed and compared. However when you talk about Camera Eye, I see it as a description of the photographer internalizing the camera as an interface so deeply that its function becomes transparent to them. A similar modality is possible with the use of social media. The person who feels frustrated because they cannot tweet their mountaintop lunch is coming up against their own expectation of sharing as an implicit act of consciousness itself.

In this sense, media are prostethics. They augment our access to reality, and our expectations towards it, by changing the very nature of how we view our own consciousness.

As always, a brilliant post!

Fear and the Digital/Actual Split » Cyborgology — August 23, 2011

[...] much of the work done on this blog, and in particular with a few recent comment threads (especially here, but also here). In response to this, I’ve devised a list of reasons why this split is so [...]

Life Becomes Picturesque: Facebook and the Claude Glass « n a t h a n j u r g e n s o n — August 29, 2011

[...] This was originally posted at my blog Cyborgology – click here to view the original post and t... [...]

Cyborgology One Year Anniversary » Cyborgology — October 26, 2011

[...] 4. Life Becomes Picturesque: Facebook and the Claude Glass [...]

Art Friday: Thinking it through… | Memoria.Arts — February 17, 2012

[...] Ali’s 52 Creative Lifts, Week 7: Life Becomes Picturesque: Facebook and the Claude Glass –this one made me think a lot about how we try to ‘frame’ life, and when we take [...]

State-Sponsored “Slacktivism”: The Social Media Campaigns of the IDF and Hamas » Cyborgology — December 9, 2012

[...] picturesque self-documentation of the soldier, according to Lemmy and Jurgenson, creates a nostalgia for a [...]

Karen Little — April 6, 2013

Since the dawn of digital photography, I've taken thousands of photos (all marvelous, I might add). At first, I felt like I was taking too many, but as I have a good eye and quick reflexes, I continued anyway.

Today, I have approximately 14 years of photos on my PC's hard drive which are in continuous display on my large, flat-screen monitor as a screen saver. They are mesmerizing! And they are the focus of reminiscing, conversation, and wonder (especially when recording stages of childhood).

Frankly, sharing travel photos with others through blogs and photo sites doesn't elicit much of a response. But seeing the photos in rotation, with time and space mixed up, does.

Life Becomes Picturesque: Facebook and the Clau... — August 17, 2013

[...] [...]

Lisa Hale — January 18, 2014

I see the Claude glass "beautification" trend and the current social media documentation trend as entirely different subjects. The former has more to do with seeing and appreciating the picturesque landscape enhanced by "rose colored glasses" that romanticizes it. However, the current obsession with documenting one's life experiences through social media constantly says to me the individual is screaming for attention and validation and a bit of self-aggrandizement . I think most people do try to spin the image of their life to appear better than it really is, however, I have come across a few who like to share their woes but to the same end. They are not "documenting" for themselves, they are "marketing" themselves.

Press Release Writing — April 1, 2014

What's up to every one, the contents existing at this web page are in fact remarkable for people experience, well, keep up the

nice work fellows.

Winter Break Research | Remembering Remembering — January 21, 2015

[…] Claude Glass metaphor presents the social media user as turned away from lived experience in order to present […]