Bearing in mind the obvious disparities created by the digital divide, how does Web 2.0 offer spaces for resistance for minority populations and historically silenced groups? Although the primary beneficiaries of new internet technologies has historically been white males, recent developments in handheld technologies have admitted several minority populations to the world wide web for the first time (the homeless, working class groups, low income African Americans, non-Western users, etc.). In addition, Web 2.0 offers opportunities for minority perspectives to be heard in ways that traditional top-down media outlets do not. For instance, the blogosphere is awash with feminist blogs and progressive voices normally silenced by mainstream media. Similarly, the internet has provided avenues for people separated by geographical distance to coalesce and converse online. I have in mind here diasporic communities that now span the globe and can access one another via the world wide web. Finally, new group formations around shared interests (such as MMO gaming) yield opportunities for counter-ideologies to gain momentum and successfully challenge prevailing ideologies on particular websites and internet landscapes.

In this panel– fully titled,“Counter-Discourses: Resistance and Empowerment on Social Media” – we will be discussing these themes and more. Sabrina Weiss’ “Cyber-liberation: From Egypt to Azeroth” discusses the world of MMO gaming and its role in disrupting gender expectations. Rather than focus on men who use female avatars, Weiss focuses on a less visible group, women who use male avatars in their online gaming. She discusses how the internet overcomes the limitations of face-to-face communication by permitting individuals to safeguard potentially incriminating information about themselves. In this case, women can choose not to reveal their gender and thereby avoid sexist backlash from other male players. But is such subterfuge a form of resistance?

Similarly, Andrew Lynn’s piece “Authenticity FAIL: The Internet as Resistance to Popular Culture” discusses the ability of users to challenge and subvert the ideologies and messages of popular culture, thereby creating counter-discourses. More specifically, Lynn reflects on how users deconstruct and critique messages of mainstream media, revealing hypocrisies, contradictions, and implicit trends in consumer advertising and other media texts, most often through the use of humor. In this way, Lynn shows us how the backstage behavior of users on Web 2.0 becomes visible and made public through user-generated content. But does such behavior successfully challenge the hegemony of the mass media in the material world?

In a similar vein, Randy Lynn and Jeff Johnson’s “‘Bitches Love’ Ambiguous Sexism: Gender, ‘Karma,’ and the Limits of Male Progressivism in Online Communities” looks closely at Reddit.com, a user-driven website where content is ranked and rated by up and down arrows to yield a “karma” score. This “karma” score reflects the collective value attached to the given website, link, video, content, etc. Lynn and Johnson pay particular attention to constructions of gender ideology on Reddit, revealing the dichotomous trends towards misogyny and feminism that prevail online. Although the users of Reddit are primarily male, they are also largely progressive. This leads to a polarization of views on gender, where the most extreme views get high karma scores. But do these trends simply mirror larger political trends in the offline world? What does the political polarization online tell us about the offline world?

Finally, Jes Koepfler and Derek Hansen’s “Connecting: A Case Study of a Twitter Network for the Homeless” draws attention to an oft-misunderstood group of internet users: the homeless. Though this group is often overlooked in discussions of new media technologies, the homeless are becoming an integral part of Web 2.0. Koepfler and Hansen seek to understand how this group uses Twitter to express themselves and make their views heard. In short, Koepfler and Hansen seek to make this traditionally “invisible” group “visible” by outlining how the homeless use Twitter. But does Twitter actually give the homeless a voice or does it simply reify the “silencing” of the homeless in the material world? With celebrities gaining the most visibility on Twitter (http://twitaholic.com/), what does this mean for the homeless who make have much narrower social networks?

Sabrina Weiss, “Cyber-liberation: From Egypt to Azeroth”

Sabrina Weiss, “Cyber-liberation: From Egypt to Azeroth”

The medium of the Internet is both self-powered and self-empowering for those who use it to create personas that control the amount and type of metadata released to other users in online social environments. Since all interactions on the Internet are filtered based on the preference of the user, the sharing of metadata can be controlled closely, unlike in the offline world. This makes it possible for members of marginalized groups to transcend face-to-face social limitations imposed on them and participate more fully and actively in social communities built around cyber-identities and cooperative/competitive activities.

In studies of MMO avatar gender-bending, most research has focused on why males play female avatars because they comprise a highly visible group, both culturally and statistically. By contrast, the number of female players who play male avatars is apparently very small, resulting in dismissal as academically uninteresting. As a member of this extreme minority who has definite reasons for exclusively playing male avatars, I want to share my personal experiences and observations to offer a new perspective on this rare phenomenon that may not in fact be so rare. When offline gender expectations are kept out of game, a female player is allowed to develop camaraderie and respect based on ability and skill untainted by gender norms and stereotypes. Through this discussion, the larger theme of identity control through the medium of the Internet is explored.

Cyber-liberation comes not just from withholding offline identity metadata, and it can concern larger issues than recreational gaming, like offline liberation. In some cases, such as in the Tahrir Square protests, it was empowering for women to be seen actively calling for protests both online and in the streets. The YouTube videos posted by activists like Aasma Mahfouz are powerful partly because one can see that they are women making powerful statements from a position presumably of disempowerment. From this, it can be surmised that a group that is more disempowered in offline interactions by metadata will potentially gain more from access to online social technologies because they will have the choice whether or not to release that information as appropriate to the situation.

Andrew Lynn, “Authenticity FAIL: The Internet as Resistance to Popular Culture”

Andrew Lynn, “Authenticity FAIL: The Internet as Resistance to Popular Culture”

Past research has focused on the internet and blogosphere as a medium where vernacular voices can challenge institutional authority and the hegemonic discourses that dominate more traditional media sources. While the effectiveness of digital activism has been debated within both academic and popular circles, less attention has been given to the internet’s ability to challenge hegemonic images and narratives within advertising, politics, and popular culture. Theories of culture and ideology often overlook the “cultural autonomy” of online space, which possesses unique abilities to facilitate a dialogical contestation of popular culture and its legitimacy.

One particular means of contestation has become prevalent throughout the blogosphere: evaluating, challenging, or unmasking cultural items for their perceived inauthentic representation of reality. In this presentation I look at several internet-based cultural objects—online videos, blogs, images, remixes, parodies—that fit within an “authenticity FAIL” genre of online culture. These items draw on the temporal and spatial freedom of the internet to provide new contexts to images, narratives, and values propagated by traditional media. This recontextualization highlights the formulaic and thereby challenges authenticity. Examples would be synching up of the 2008 Presidential Debates or stitching together infomercials to highlight unoriginality. Other examples involve spotting patterns in advertising images that suggest particular marketing tropes.

The ability of this phenomenon to impact discourse warrants new appreciation for the internet as a “site of contestation” for those seeking cultural or societal influence. There are many continuities with earlier anti-consumerism “culture jammers,” particularly the thought of Guy Debord and his conception of modifying advertising to subvert its meaning (détournement). At the same time, these tactics have been modified and popularized to new levels within online space: a diverse group of vernacular, activist, and even institutional voices have latched onto them as means of persuasion. In drawing on Sloterdijk’s conception of “resistant kynicism,” I examine how these items might embody a larger resistance effort of preserving authenticity and meaning within an increasingly consumer-driven and mediated cultural universe. While avoiding overly utopian interpretations, I argue the rise of participatory online space mirrors past media revolutions and thus requires greater reflection on the continuities and changes in culture, power structures, and public discourse.

Randy Lynn (and Jeff Johnson), “‘Bitches Love’ Ambiguous Sexism: Gender, ‘Karma,’ and the Limits of Male Progressivism in Online Communities”

Randy Lynn (and Jeff Johnson), “‘Bitches Love’ Ambiguous Sexism: Gender, ‘Karma,’ and the Limits of Male Progressivism in Online Communities”

The Internet has long been studied as a space in which hegemonic masculinities have been reinforced and challenged. On one hand, the semi-public nature of the Internet enables confrontations and rebuttals to sexist and masculinist ideologies; on the other hand, the same semi-public nature allows sexist and masculinist ideologies to proliferate. Moreover, stereotypes of gendered work ensure that Internet communities frequented by technologically literate populations are construed as masculine spaces, in which masculinist perspectives may be implicitly or explicitly sanctioned while feminist perspectives are ignored, belittled, or suppressed.

This study investigates gender relations among users of Reddit, a social news website with 13 million unique monthly visitors. Reddit users conceive of themselves as a population in which men are a majority, although a significant minority of users claim to be women. They also conceive of themselves as being younger, more politically progressive, and less socially adept than the population at large. Users create posts or submit hyperlinks to Internet content, which other users may evaluate positively by casting an “upvote” and negatively by casting a “downvote.” The net score is collectively referred to as “karma.” “Link karma” determines the visibility of links within the subforum to which it was submitted, while the links with the highest karma are displayed on the front page of the site. Reddit users may comment upon posts or links, and these user comments are also quantified by means of upvotes and downvotes. “Comment karma” determines the visibility of comments within an online discussion surrounding a post or link.

The characteristics of Reddit and its user population render the site uniquely amenable to a mixed method approach combining discourse analysis and quantitative methods. Although most users claim to be men, a significant minority claims to be women. Moreover, the progressive political inclination of Reddit’s user population yields a significant subset of male users who resist masculinist discourses. However, many male Reddit users propound and support masculinist discourses, including those that are hostile to women. Discussions of gender relations are common at Reddit, and often both masculinist and feminist discourses will be represented and receive high comment karma. A sample of comments drawn from front-page links or posts will be situated in the particular discursive and cultural contexts of Reddit, linking comments to broader cultural practices such as the use of humor.

In addition, the karma model provides a direct measure of the support (or lack thereof) for comments espousing particular norms and attitudes toward gender. This study draws from the literature of ambivalent sexism to construct categories of sexist and anti-sexist discourse and uses regression methods to identify the most popular discourses, while controlling for other factors that may influence the karma of a comment (such as a user’s overall karma or when the comment was submitted). This analysis will engage with previous findings regarding the “silencing” of oppressed populations, the dissonance between progressive political ideologies and the support of patriarchal perspectives, and the broader literature of gender relations in online communities. Implications and limitations will be discussed.

Jan Koepfler ([(@jeskak] and Derek Hansen) , “Connecting: A Case Study of a Twitter Network for the Homeless”

Jan Koepfler ([(@jeskak] and Derek Hansen) , “Connecting: A Case Study of a Twitter Network for the Homeless”

I became interested in how marginalized groups were using social media during HCIL Service Day last year (http://www.cs.umd.edu/hcil/designingforabetterworld/). When I told friends and colleagues that I would be working with a homeless shelter to help redesign an area of their website that was for their clients, I often received funny looks and remarks like, “But why would homeless people need a website?” When I got to the shelter on Service Day and listened as the group debated how to change the information architecture of the site, I couldn’t help but think how much easier the decision-making process would have been if we had our key stakeholders-the homeless clients of ThriveDC-in the room with us.

This experience raised questions about online participation and social media use by the homeless. Were they in the same social spaces as everyone else (e.g. Twitter)? With the potential benefits of anonymity on the web, would we even find anyone identifying as homeless? A primary goal of this first pilot study was to simply dispel some myths around homelessness and technology, and to build a case for future research in this area.

Homelessness affects those who may be sheltered or unsheltered, as well as “doubled-up” – those who move from the couch of one friend, family member, or acquaintance to another, and may never access homeless services. Understanding the breadth of the issue and the environmental contexts for homelessness is important because it quickly changes one’s perceptions of what it means to be homeless and the potential points of access one may have to online networks. Research shows that although the homeless lack certain material resources, many have access to information and communication technologies through public libraries, computer labs in day shelters, and mobile technologies (Eyrich-Garg, 2010, 2011; Roberson & Nardi, 2010).

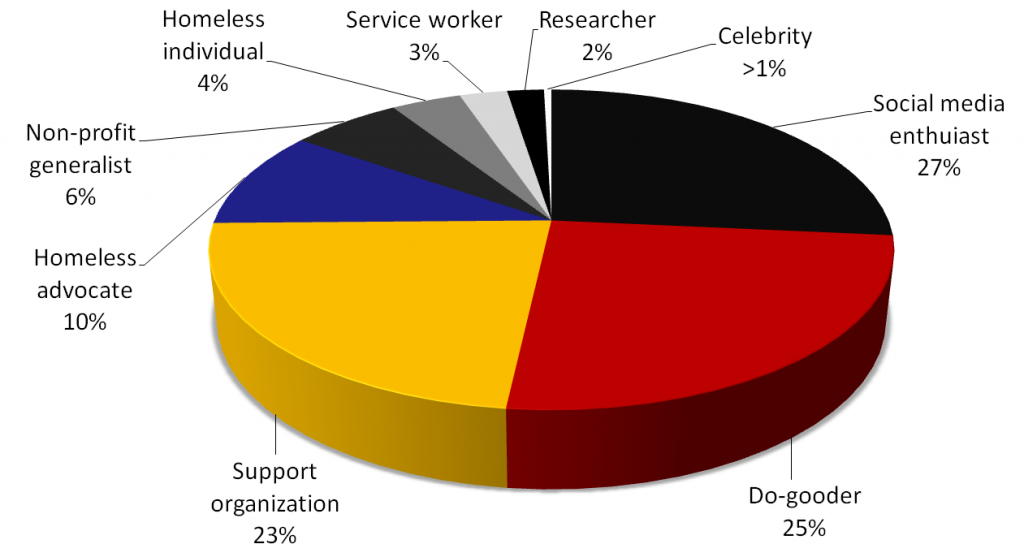

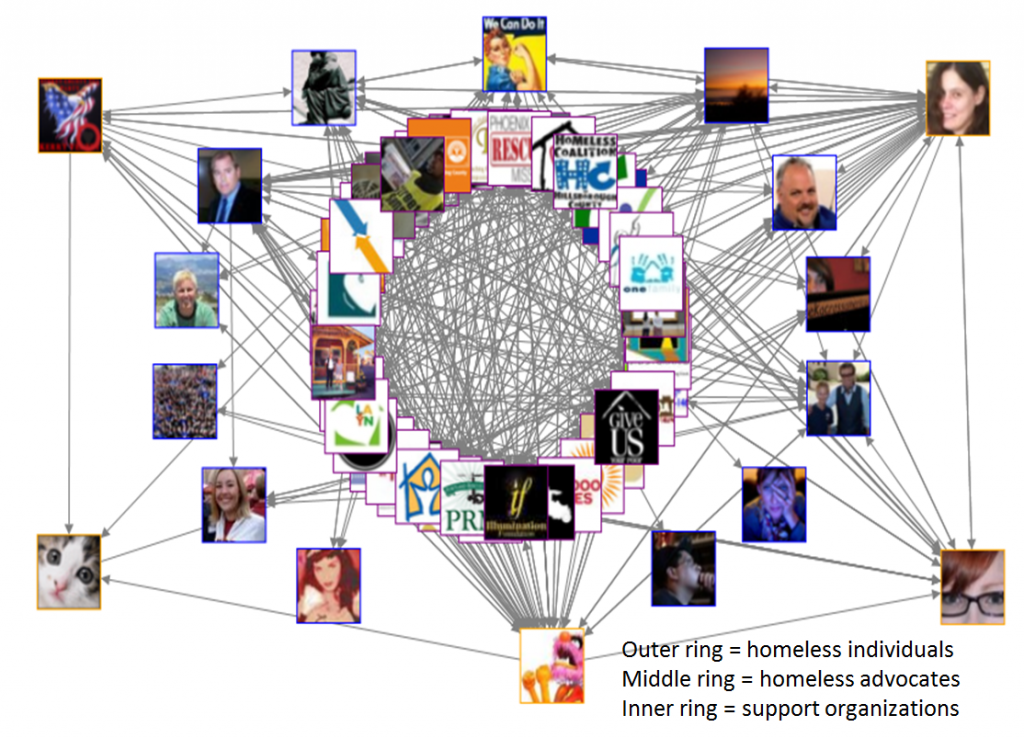

Identifying and counting the homeless is challenging enough given the broad range of reasons for becoming homeless and the myriad places homeless people stay (e.g. in shelters, in cars, under bridges, on couches, in motels, etc.). Finding homeless people online posed a similar challenge, so we started with a known network on Twitter called @wearevisible. The goal of the We Are Visible project (www.wearevisible.com) is to empower homeless people to use social media and the web to bring a human voice to the issue of homelessness. Although the network was only 4 months old at the time of the study, we were able to address two key questions:

- To what extent are homeless individuals using the @wearevisible network?

- In what ways are homeless individuals connected to each other and other types of users in the @wearevisible network?

Example bios from Homeless individuals:

“@bedbugsbite22: Former yuppie, now homeless. Shit happens – at least sometimes it’s funny.”

“@alifumich: Living in my camper w/ my husband, dog and 3 cats. Jobless, homeless, but can still smile!”

The results have inspired a series of follow-up research questions related to online vs. offline information diffusion and resource access, and highlight opportunities to think about the design of online communities to support marginalized individuals.