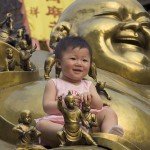

See more of my photos of children and families in China on my flickr page.

I went on this trip to learn first-hand about China, as much as could be learned in sponsored tour of 10 days! I learned an incredible amount, especially by observing life as best I could in Beijing, Xi’an, Hangzhou, and Shanghai, and talking to our tour guides, other people I met who spoke English, and the faculty and students at Peking and Fudan Universities. I’ve decided to narrow my blog entries to specific thoughts on specific issues.

One of the things that most impressed me was how the one-child policy combines with massive rural-urban migrations to create the potential for significant change in China. The one-child policy is one of the first things that American friends and acquaintances brought up to me when I mentioned that I was going to China. Most Americans view this policy with horror, and the large number of child deaths in the recent earthquake only reinforces the antipathy. “Oh my, their only child died, and they can’t have another. How tragic!” Of course, I agree about the tragedy, but those of us aware of the massive problems of feeding, housing, and employing the growing Chinese population recognize that something had to be done, and, as our own politicians like to say at election time, “Someone has to make the hard decisions.”

One of the things that most impressed me was how the one-child policy combines with massive rural-urban migrations to create the potential for significant change in China. The one-child policy is one of the first things that American friends and acquaintances brought up to me when I mentioned that I was going to China. Most Americans view this policy with horror, and the large number of child deaths in the recent earthquake only reinforces the antipathy. “Oh my, their only child died, and they can’t have another. How tragic!” Of course, I agree about the tragedy, but those of us aware of the massive problems of feeding, housing, and employing the growing Chinese population recognize that something had to be done, and, as our own politicians like to say at election time, “Someone has to make the hard decisions.”

So my sense from my visit is that the Chinese largely understand and accept this policy, and go about their business of living. All over China, I saw mothers and a child, fathers and a child, couples with a child, grandparents with a child. Single children were carried on bicycles and motorbikes in rush hour traffic every morning and evening. Tourist sites were overwhelmed with families with one child.

So my sense from my visit is that the Chinese largely understand and accept this policy, and go about their business of living. All over China, I saw mothers and a child, fathers and a child, couples with a child, grandparents with a child. Single children were carried on bicycles and motorbikes in rush hour traffic every morning and evening. Tourist sites were overwhelmed with families with one child.

The result of all this, in the words of one of the sociologists we met at Peking University, is the “1980s generation.” Policy makers, scholars, and the general public seem to be concerned that the new generations are being spoiled! Their wishes are being catered to; they are only interested in new technology; they are too individualistic; they don’t understand what “we” went through in the Cultural Revolution (a topic for another blog); they take their privileges for granted. China Daily, the English language newspaper (or propaganda sheet!), reported on 6 June 2008 that the People’s Congress in the province of Liaoning drafted legislation making it “an obligation for adult children to contact or visit their parents regularly….Government employees, who fail to do so, will face sanctions by their respective agencies.” The newspaper reported that they expect the draft to become law by the end of the year. The fact that such a law is being considered, mentioned in an English language periodical, and is expected to be passed, shows the depth of concern.

Of course some of these sentiments are quite common when families are caught up in social change. Similar reactions are often expressed within immigrant families in America and worldwide. The notion that the young don’t understand what the old went through, or what elders sacrificed, is a common theme in ethnic literature and scholarship (Japanese-American, African-American, Hispanic-American, white-ethnic-American, etc).

What is different about China, however, is that many seem to fear that the centuries-old, collectively focused, Chinese culture is at risk. It’s almost as if they are asking, “How will the revolution be continued, when we are raising little Westerners?” I, of course, don’t have an answer to this question, but it may create the conditions for cultural change beyond the grasp of the planned social and economic changes that Chinese leaders are presenting. The new generations are privileged beyond the dreams of their parents, and with affluence comes cultural change. I don’t see how the clock can be turned back.

What is different about China, however, is that many seem to fear that the centuries-old, collectively focused, Chinese culture is at risk. It’s almost as if they are asking, “How will the revolution be continued, when we are raising little Westerners?” I, of course, don’t have an answer to this question, but it may create the conditions for cultural change beyond the grasp of the planned social and economic changes that Chinese leaders are presenting. The new generations are privileged beyond the dreams of their parents, and with affluence comes cultural change. I don’t see how the clock can be turned back.

Rural-urban migration issues in China illuminate a different facet of these issues, and this migration is vast. For example, we were told that Shanghai now has 19 million people, and that over 5 million are migrant workers. In China, you are “registered” in the province of your birth. Moving is easier now than historically; one can move in search of employment and, if successful, one’s employer helps with a residency visa in the new province that might last for 1 or 3 years. After that temporary period, a permanent visa can be obtained if one has skills needed in the new province. As in most migration streams, these tend to follow kinship linkages.

Nevertheless, migrant workers are presenting significant challenges for the new urban economies. It is startling to me that every student who spoke to us at Fudan University was interested in studying some aspect of the generational effects of this migration. Some married couples migrate to the urban areas, but leave their children in the provinces with their grandparents. Others couples migrate with their children. In the former case, parents look forward to the time that the family can get back together, after the children have finished college and joined them. In the latter case, the Chinese students were reporting that they never see their parents, since both are working all the time, and actually feel closer to their grandparents back in the rural provinces. Without the attention of their parents, many young people are getting involved with various delinquencies, such as drugs, alcohol, sex, and crime. The generation gap is thus exacerbated. To make matters worse, public education is funded at the province level, and municipalities like Shanghai are reluctant to provide education through high school for the children of migrants. These children, therefore, will have to return to the provinces for high school education, or drop out and enter the shadowy world of the informal economy.

Nevertheless, migrant workers are presenting significant challenges for the new urban economies. It is startling to me that every student who spoke to us at Fudan University was interested in studying some aspect of the generational effects of this migration. Some married couples migrate to the urban areas, but leave their children in the provinces with their grandparents. Others couples migrate with their children. In the former case, parents look forward to the time that the family can get back together, after the children have finished college and joined them. In the latter case, the Chinese students were reporting that they never see their parents, since both are working all the time, and actually feel closer to their grandparents back in the rural provinces. Without the attention of their parents, many young people are getting involved with various delinquencies, such as drugs, alcohol, sex, and crime. The generation gap is thus exacerbated. To make matters worse, public education is funded at the province level, and municipalities like Shanghai are reluctant to provide education through high school for the children of migrants. These children, therefore, will have to return to the provinces for high school education, or drop out and enter the shadowy world of the informal economy.

Of course, these generational migration problems would be occurring regardless of the one-child policy. But that policy highlights significant contradictory results in today’s China. Children born to urban families are “being spoiled.” Children born to migrant workers, on the other hand, are facing the difficult situation of being cast into the urban world with fewer controls on their behavior, and an uncertain sense of belongingness. Both cases are creating a cultural change large enough for attempts to legislate morality (to use an American political phrase), and will likely lead to greater individualism in a society that has long prided itself on a collective mentality.

Comments 3

Frank Mara — August 21, 2008

Hi Larry - I'm watching the Olympic Games and I went back to look at some of the photos from your China trip on Flickr. I think one of the hardest things for us to understand is the intense sense of national identity the Chinese have. As Americans, we have lots of issues with the Chinese Government and we look upon their country's economic growth with trepidation. However, we don't fully understand Chinese society and values. We need to, for both our national security and economic well-being. Your photos provide a portal into Chinese society that we rarely get to see.

Larry Troy — August 21, 2008

Thanks for your comment Frank. Learning something about Chinese society and values was the reason I took the trip. And many of the photos I took and posted to flickr were as a visual sociologist trying to capture the culture and society as I saw it. Thanks for appreciating them in that light. I'm moving on now to process the tourist shots I took, but I wanted to get the photos on seniors, children, gardens, the hutongs, and workers up first. They were the expression of the sociologist in me.

I must say that the reading I did in Chinese history and culture before the trip was indispensible for preparing me for what I saw and learned once I got there. The Chinese have a strong national pride, and are very aware, and proud, of their centuries-long history.

Just beneath the surface is the comparison of today with life during the Cultural Revolution in the 1970s. They seem to look upon that period of time in a similar fashion to the way we in the West look at the Depression of the 1930s. "It was something out of our control, and people who survived went through really hard times that affected their values for the rest of their lives." At least outwardly, they do not seem to blame particular people for those events (perhaps Madame Mao more than anyone). (Regarding Chairman Mao and the Cultural Revolution, one woman told us, "Everyone's entitled to one mistake!") They don't know the real history of this time, and want to forget the hardships and deaths, and are too busy marveling at the changes in their own country in the past 20-25 years.

Without a strong sense of democracy in their basic values, most Chinese seem to accept their national leaders, and trust the direction these leaders have taken with the economy and the resulting improvement of their lives. In present-day China, most urbanites are living a far better life than their parents did, and conceive of their lives in that way. (I keep recalling their saying, "Heaven is high and the Emperor is far away.") From that perspective, democracy seems both irrelevant and scary. It seems to imply instabilty and unplanned change. I think democracy will come to China, but it will be a very slow evolution, and when you're talking about a quarter or a fifth of the population of the whole planet, maybe that makes sense.

On the other hand, there is quite a lot of political activism and suppressed dissent over many issues: religious and cultural freedom and worker rights are two of them. Ultimately, Chinese leaders are dealing with these issues in an amazingly slow evolutionary process. And for middle-class Chinese, that is OK with them. For example, a sociologist at Fudan University told us that he preferred McCain to Obama, because he thought that Obama would pressure China on human rights and workers' rights, which he saw as detrimental to China's progress! What would the workers say? I think there would be a mixture of acceptance of one's fate, appreciation for the opportunity to work and make money at all, and a vague, disorganized wish that things could be better. But they're not going to stick their neck out too far.

Someday, China will deal with its current repression and oppression of workers and minorities, and it will be interesting to see how they re-write their own history, but I don't expect to see it in my own lifetime.

rosh — March 22, 2010

In my sociology class we are reading about how in America there is a large gap between the rich and the poor. One of the main concerns of studies on this topic is that in poor families the way that children are raised is negatively affected. I think the one-child policy is something that may possibly influence situations such as these. Having only one child would definitely influence the family dynamic differently since the concept of siblings is removed however it may also allow parents to more properly raise their children since they only have to afford things for one child. This may then lead to a lower poverty rate in the future since children can be raised with a better education and be more well-prepared for the job world. As a whole this policy may shrink the inequality gap of China.