I just finished a new set of photos from my China trip, this time on Workers in China. See them here on flickr.

See more photos related to this blog post at this flickr page.

On Monday, June 2, 2008, my first full day in Beijing, I got into a pedicab with Leo Goodman.We were being taken through the hutongs of the Shichahai neighborhood to have lunch in a family’s home. A sign for tourists in that neighborhood reads in both Chinese and English: “Hutong refers to the unique old alleys in Beijing. The word, which derives from Mongolian, was brought to Beijing over 700 years ago, when the Yuan Dynasty built Badu here.”

On Monday, June 2, 2008, my first full day in Beijing, I got into a pedicab with Leo Goodman.We were being taken through the hutongs of the Shichahai neighborhood to have lunch in a family’s home. A sign for tourists in that neighborhood reads in both Chinese and English: “Hutong refers to the unique old alleys in Beijing. The word, which derives from Mongolian, was brought to Beijing over 700 years ago, when the Yuan Dynasty built Badu here.”

I was pretty excited to be in this neighborhood, because I’d seen photos taken by two of my favorite photojournalists, Sean Gallagher and Zoriah, of the destruction of the hutongs in Beijing.  But here I was being pulled by a man driving a big tricycle through a very real and very attractive neighborhood. It became clear to me that this neighborhood had been preserved and restored, while others had been destroyed. There were many new cars parked on the streets and signs of new construction everywhere.

But here I was being pulled by a man driving a big tricycle through a very real and very attractive neighborhood. It became clear to me that this neighborhood had been preserved and restored, while others had been destroyed. There were many new cars parked on the streets and signs of new construction everywhere.

When we stopped at our luncheon place, I noticed a sign out front that advertised “Chinese Famous Snack: DonkeyMeatSausage.”  The food was delicious; I don’t think they served us that particular delicacy. The two-room residence where we had lunch was rented for about $75 a year from the government by a couple who had raised their children there. They were both retired now, living on a government pension, and supplementing their income serving lunch to tourists. They were fortunate that they had running water and their home opened onto the street, giving them a front porch. Other families rented the other homes in the courtyard residence.

The food was delicious; I don’t think they served us that particular delicacy. The two-room residence where we had lunch was rented for about $75 a year from the government by a couple who had raised their children there. They were both retired now, living on a government pension, and supplementing their income serving lunch to tourists. They were fortunate that they had running water and their home opened onto the street, giving them a front porch. Other families rented the other homes in the courtyard residence.

After returning from China, I learned some of the history of the hutongs by doing some web research on Wikipedia and followed other links; parts of this blog are lifted from those sources. During the long dynastic periods of Chinese history, the Forbidden City was placed at the center of Beijing, and was surrounded by two concentric circles, called the Inner City and the Outer City. The higher your status, the closer you could live to the center of the circles. Aristocrats and wealthy merchants tended to live to the east and west of the imperial palace. The working class and lesser merchants lived to the north and south.  The typical homes, called siheyuan, were built around courtyards. The four buildings of a siheyuan were normally positioned along the north-south and east-west axes, with passages separating the buildings and connecting to the courtyards. All of the rooms around the courtyard had large windows facing onto the yard and small windows high up on the back wall facing out onto the street. The entrance gate, usually painted vermilion and with copper door knockers, was usually at the southeastern corner, and a pair of stone lions was sometimes placed outside the gate. The alleys from which one entered the siheyuan were called hutongs. The hutongs in the wealthy areas were orderly, and lined by spacious homes and walled gardens. The working class neighborhoods had more haphazard hutongs, which were narrower with many turns and angles. The siheyuan on these were of course smaller and simpler.

The typical homes, called siheyuan, were built around courtyards. The four buildings of a siheyuan were normally positioned along the north-south and east-west axes, with passages separating the buildings and connecting to the courtyards. All of the rooms around the courtyard had large windows facing onto the yard and small windows high up on the back wall facing out onto the street. The entrance gate, usually painted vermilion and with copper door knockers, was usually at the southeastern corner, and a pair of stone lions was sometimes placed outside the gate. The alleys from which one entered the siheyuan were called hutongs. The hutongs in the wealthy areas were orderly, and lined by spacious homes and walled gardens. The working class neighborhoods had more haphazard hutongs, which were narrower with many turns and angles. The siheyuan on these were of course smaller and simpler.

The conditions of the hutongs deteriorated at the end of the Qing Dynasty, and continued to decay through the end of World War II. Siheyuan previously owned and occupied by a single family were subdivided and shared by many households, with additions tacked on as needed, built with whatever materials were available. The 978 hutongs listed in Qing Dynasty records swelled to 1,330 by 1949. Following the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, many of the old hutongs disappeared, replaced by the high rises and wide boulevards of today’s Beijing. Demolition continued at a faster pace starting in the 1990s, as Beijing modernized, and then accelerated again in the 21st century as China prepared for the 2008 Olympics.

The conditions of the hutongs deteriorated at the end of the Qing Dynasty, and continued to decay through the end of World War II. Siheyuan previously owned and occupied by a single family were subdivided and shared by many households, with additions tacked on as needed, built with whatever materials were available. The 978 hutongs listed in Qing Dynasty records swelled to 1,330 by 1949. Following the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, many of the old hutongs disappeared, replaced by the high rises and wide boulevards of today’s Beijing. Demolition continued at a faster pace starting in the 1990s, as Beijing modernized, and then accelerated again in the 21st century as China prepared for the 2008 Olympics.

The extent of destruction of siheyuan is startling. Today, the area occupied by siheyuan has shrunk from 17 million square meters in the early 1950s to just three million square meters. For example, between only 1990 and 1998, a total 4.2 million square meters of old housing was destroyed. The Beijing Yearbook 2003 reported that more than 60 hutongs vanished during 2002 alone, and the Beijing Municipal Construction Committee stated in 2004 that some 250,000 square meters of old housing – 20,000 households – would be demolished in 2004.

According to the Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage, there are over 3,000 “well-preserved” courtyards remaining in Beijing, and over 539 are in Cultural and Historical Conservation Areas, including those found in the Shichahai Lake neighborhood we visited. In 2004, the Beijing Municipality began encouraging the sale of siheyuan, including the real estate, in order to protect the remaining hutong areas. Many of these are for sale, and are being bought and renovated by foreigners, including wealthy developers from Hong Kong and Taiwan. More typically, however, siheyuan are being used as housing complexes, hosting multiple families, with courtyards being developed to provide extra living space. The living conditions in many siheyuan are considered squalid, with very few having private toilets.

According to the Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage, there are over 3,000 “well-preserved” courtyards remaining in Beijing, and over 539 are in Cultural and Historical Conservation Areas, including those found in the Shichahai Lake neighborhood we visited. In 2004, the Beijing Municipality began encouraging the sale of siheyuan, including the real estate, in order to protect the remaining hutong areas. Many of these are for sale, and are being bought and renovated by foreigners, including wealthy developers from Hong Kong and Taiwan. More typically, however, siheyuan are being used as housing complexes, hosting multiple families, with courtyards being developed to provide extra living space. The living conditions in many siheyuan are considered squalid, with very few having private toilets.

Being a professional “peeping Tom,” as C. Wright Mills called social scientists in The Sociological Imagination, I wasn’t satisfied with my pedicab drive through the restored Shichahai neighborhood. Where were the “real” hutongs? Passing up a trip to a jade and pearl marketplace late one afternoon, I walked to the Qianmen Hutong, just southwest of Tiananmen Square to get a look. I saw a very busy residential and commercial district, with winding streets and alleys, and many small shops.  The streets were crowded with neighbors walking and biking home after work. Children were playing in the puddles that had formed from the day’s rain, and elderly people were sitting in chairs suspiciously watching a tall, western tourist with a white hat ask if he could take their picture. Smells from the food stores and small restaurants mixed with less agreeable odors from the old homes and streets and an occasional whiff of sewage. I followed one elderly woman from her home down an alley, passing her as she went into a public toilet. A few other Westerners were spilling out of a youth hostel on one of the more commercial streets, called “Shopping Street” on my map. I remembered staying in similar hotels in Paris during my college days, and I thought of the 5-star hotel I’d be returning to.

The streets were crowded with neighbors walking and biking home after work. Children were playing in the puddles that had formed from the day’s rain, and elderly people were sitting in chairs suspiciously watching a tall, western tourist with a white hat ask if he could take their picture. Smells from the food stores and small restaurants mixed with less agreeable odors from the old homes and streets and an occasional whiff of sewage. I followed one elderly woman from her home down an alley, passing her as she went into a public toilet. A few other Westerners were spilling out of a youth hostel on one of the more commercial streets, called “Shopping Street” on my map. I remembered staying in similar hotels in Paris during my college days, and I thought of the 5-star hotel I’d be returning to.

Old bicycles and new cars were parked on the streets and alleys of the hutong. I surmised that the cars belonged to those residents who had purchased entire siheyuan, while the bikes were owned by those living in the smaller buildings within the courtyards, like the two-room residence in which I was served lunch a few days before. The doors to many of the siheyuan had been left open, and I used my professional “Peeping Tom” status to gaze into them and photograph as many as I could. Typically, a crwded, cluttered alley presented itself that ended in a right angle turn beyond which I couldn’t see. There were often clothes hanging on a line, and many bikes parked there. Occasionally, I’d see a child or adult walking in or out of the alley, and I felt exposed and embarrassed for being an interloper. Didn’t they know I was a professional and allowed to gaze? In smaller alleys I saw a grandfather accompanying a child on a bike with training wheels, a group of men hunched over some kind of board or card game, and many people just passing through as they went about their business in their neighborhood. Overall, about as many people smiled at me as viewed me with suspicion or scorn.

Construction was everywhere. As I approached this neighborhood from Tiananmen Square on the north, I passed a construction site similar to those seen in any big city. Looking through a gap in the wall, I saw a demolished neighborhood similar to those I saw in Zoriah’s photos. Workers were using hand saws and ancient wheelbarrows to build a new neighborhood. When I crossed the street into Qianmen I had to bypass barricades designed to keep pedestrians away from the building activity on the street. Within the hutong itself I also saw occasional open lots with a few men working to restore an old shell of a home.

Construction was everywhere. As I approached this neighborhood from Tiananmen Square on the north, I passed a construction site similar to those seen in any big city. Looking through a gap in the wall, I saw a demolished neighborhood similar to those I saw in Zoriah’s photos. Workers were using hand saws and ancient wheelbarrows to build a new neighborhood. When I crossed the street into Qianmen I had to bypass barricades designed to keep pedestrians away from the building activity on the street. Within the hutong itself I also saw occasional open lots with a few men working to restore an old shell of a home.

I’m thrilled with my solo walk through the Qianmen Hutong looking for the “real” Beijing. Did I find it? I have no way of knowing. But it was surely a closer view than I received from the 5-star hotels and the windows of a tour bus during the rest of the trip. And it provides me with a strong visual memory of the history I read when I got home. I hope my photos give you a sense of my experience.

I think it was Brent Shea from Sweetbriar College, who uttered these words. At the time, if I remember correctly, we were walking through the garden outside the Temple of Heaven in Beijing. We passed through scores of groups of people, all likely over 55 years of age, each engaged in some activity. There were Go players, card players, and many different groups of singers and musicians (even one man with an accordion singing with a group, not far from a man playing a traditional erhu). They all seemed to be having a wonderful time. I marveled at the variety of activity on a weekday afternoon, and the obvious joy these people displayed. But I kept asking myself, “What’s going on here?” When we got a chance to talk to our tour guide, we found out that this garden is an informal meeting place for people who want to get together. They pay some nominal, annual fee and can visit as often as they like. They join groups to learn and play games, sing and dance, and socialize.

I think it was Brent Shea from Sweetbriar College, who uttered these words. At the time, if I remember correctly, we were walking through the garden outside the Temple of Heaven in Beijing. We passed through scores of groups of people, all likely over 55 years of age, each engaged in some activity. There were Go players, card players, and many different groups of singers and musicians (even one man with an accordion singing with a group, not far from a man playing a traditional erhu). They all seemed to be having a wonderful time. I marveled at the variety of activity on a weekday afternoon, and the obvious joy these people displayed. But I kept asking myself, “What’s going on here?” When we got a chance to talk to our tour guide, we found out that this garden is an informal meeting place for people who want to get together. They pay some nominal, annual fee and can visit as often as they like. They join groups to learn and play games, sing and dance, and socialize.

The sociological relevance of this is the retirement age in China: 50 for women and 55 or 60 for men, depending on whether they were manual or non-manual workers. There seems to be a social obligation to retire, given that so many people are entering the work force. Once retired, they receive a government pension the size of which depends on their income, sort of like a graduated social security system. One rub is that farmers don’t get this pension, which makes the one-child policy particularly onerous for them. Another is that you only get the pension in the province in which your residency is registered.

The sociological relevance of this is the retirement age in China: 50 for women and 55 or 60 for men, depending on whether they were manual or non-manual workers. There seems to be a social obligation to retire, given that so many people are entering the work force. Once retired, they receive a government pension the size of which depends on their income, sort of like a graduated social security system. One rub is that farmers don’t get this pension, which makes the one-child policy particularly onerous for them. Another is that you only get the pension in the province in which your residency is registered.

The World Health Organization reports that the Chinese life expectancy at birth is 72/75 (m/f), and has been rising dramatically. My guess is that there is a significant rural-urban difference, which would mean the urban population would be living longer.  So retirement ages of 50-60 translate to 20-35 years of post-employment life. These years of retirement are longer than those in the US, where we retire at 65 and can expect to live into our late 70s. Furthermore, given the one-child and residency policies, these seniors may be quite unencumbered with other obligations. Nevertheless, a young, healthy retirement with lots of free time and a culture that rewards traditional activities makes for a very nice period in the last decades of life. Hence the garden scene at the Temple of Heaven.

So retirement ages of 50-60 translate to 20-35 years of post-employment life. These years of retirement are longer than those in the US, where we retire at 65 and can expect to live into our late 70s. Furthermore, given the one-child and residency policies, these seniors may be quite unencumbered with other obligations. Nevertheless, a young, healthy retirement with lots of free time and a culture that rewards traditional activities makes for a very nice period in the last decades of life. Hence the garden scene at the Temple of Heaven.

I thought of this scene throughout the trip, especially when I would wake up early to walk the streets around our hotels before breakfast. In both Beijing and Xi’an, the gardens and squares were busy with the activity of older people.  In both cities I saw several groups of men and women doing tai chi in groups or singly, often with traditional swords or banners. In Xi’an, traditional calligraphers writing in water, whip snappers, and even groups doing Western ball dancing were added to the mix. Of course, I was in the middle of very big cities, and I have no idea about similar activities in other residential areas and other class groups. The Imperial Gardens generalize to all of China about as well as Central Park in New York would! Nevertheless, I loved the experience of seeing these older people pursuing an apparently wonderful retirement. I think I’ll keep this perception right now, rather than digging into the data to find out how wrong I am!

In both cities I saw several groups of men and women doing tai chi in groups or singly, often with traditional swords or banners. In Xi’an, traditional calligraphers writing in water, whip snappers, and even groups doing Western ball dancing were added to the mix. Of course, I was in the middle of very big cities, and I have no idea about similar activities in other residential areas and other class groups. The Imperial Gardens generalize to all of China about as well as Central Park in New York would! Nevertheless, I loved the experience of seeing these older people pursuing an apparently wonderful retirement. I think I’ll keep this perception right now, rather than digging into the data to find out how wrong I am!

See more photos related to this blog at this flickr page.

See more of my photos of children and families in China on my flickr page.

I went on this trip to learn first-hand about China, as much as could be learned in sponsored tour of 10 days! I learned an incredible amount, especially by observing life as best I could in Beijing, Xi’an, Hangzhou, and Shanghai, and talking to our tour guides, other people I met who spoke English, and the faculty and students at Peking and Fudan Universities. I’ve decided to narrow my blog entries to specific thoughts on specific issues.

One of the things that most impressed me was how the one-child policy combines with massive rural-urban migrations to create the potential for significant change in China. The one-child policy is one of the first things that American friends and acquaintances brought up to me when I mentioned that I was going to China. Most Americans view this policy with horror, and the large number of child deaths in the recent earthquake only reinforces the antipathy. “Oh my, their only child died, and they can’t have another. How tragic!” Of course, I agree about the tragedy, but those of us aware of the massive problems of feeding, housing, and employing the growing Chinese population recognize that something had to be done, and, as our own politicians like to say at election time, “Someone has to make the hard decisions.”

One of the things that most impressed me was how the one-child policy combines with massive rural-urban migrations to create the potential for significant change in China. The one-child policy is one of the first things that American friends and acquaintances brought up to me when I mentioned that I was going to China. Most Americans view this policy with horror, and the large number of child deaths in the recent earthquake only reinforces the antipathy. “Oh my, their only child died, and they can’t have another. How tragic!” Of course, I agree about the tragedy, but those of us aware of the massive problems of feeding, housing, and employing the growing Chinese population recognize that something had to be done, and, as our own politicians like to say at election time, “Someone has to make the hard decisions.”

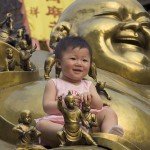

So my sense from my visit is that the Chinese largely understand and accept this policy, and go about their business of living. All over China, I saw mothers and a child, fathers and a child, couples with a child, grandparents with a child. Single children were carried on bicycles and motorbikes in rush hour traffic every morning and evening. Tourist sites were overwhelmed with families with one child.

So my sense from my visit is that the Chinese largely understand and accept this policy, and go about their business of living. All over China, I saw mothers and a child, fathers and a child, couples with a child, grandparents with a child. Single children were carried on bicycles and motorbikes in rush hour traffic every morning and evening. Tourist sites were overwhelmed with families with one child.

The result of all this, in the words of one of the sociologists we met at Peking University, is the “1980s generation.” Policy makers, scholars, and the general public seem to be concerned that the new generations are being spoiled! Their wishes are being catered to; they are only interested in new technology; they are too individualistic; they don’t understand what “we” went through in the Cultural Revolution (a topic for another blog); they take their privileges for granted. China Daily, the English language newspaper (or propaganda sheet!), reported on 6 June 2008 that the People’s Congress in the province of Liaoning drafted legislation making it “an obligation for adult children to contact or visit their parents regularly….Government employees, who fail to do so, will face sanctions by their respective agencies.” The newspaper reported that they expect the draft to become law by the end of the year. The fact that such a law is being considered, mentioned in an English language periodical, and is expected to be passed, shows the depth of concern.

Of course some of these sentiments are quite common when families are caught up in social change. Similar reactions are often expressed within immigrant families in America and worldwide. The notion that the young don’t understand what the old went through, or what elders sacrificed, is a common theme in ethnic literature and scholarship (Japanese-American, African-American, Hispanic-American, white-ethnic-American, etc).

What is different about China, however, is that many seem to fear that the centuries-old, collectively focused, Chinese culture is at risk. It’s almost as if they are asking, “How will the revolution be continued, when we are raising little Westerners?” I, of course, don’t have an answer to this question, but it may create the conditions for cultural change beyond the grasp of the planned social and economic changes that Chinese leaders are presenting. The new generations are privileged beyond the dreams of their parents, and with affluence comes cultural change. I don’t see how the clock can be turned back.

What is different about China, however, is that many seem to fear that the centuries-old, collectively focused, Chinese culture is at risk. It’s almost as if they are asking, “How will the revolution be continued, when we are raising little Westerners?” I, of course, don’t have an answer to this question, but it may create the conditions for cultural change beyond the grasp of the planned social and economic changes that Chinese leaders are presenting. The new generations are privileged beyond the dreams of their parents, and with affluence comes cultural change. I don’t see how the clock can be turned back.

Rural-urban migration issues in China illuminate a different facet of these issues, and this migration is vast. For example, we were told that Shanghai now has 19 million people, and that over 5 million are migrant workers. In China, you are “registered” in the province of your birth. Moving is easier now than historically; one can move in search of employment and, if successful, one’s employer helps with a residency visa in the new province that might last for 1 or 3 years. After that temporary period, a permanent visa can be obtained if one has skills needed in the new province. As in most migration streams, these tend to follow kinship linkages.

Nevertheless, migrant workers are presenting significant challenges for the new urban economies. It is startling to me that every student who spoke to us at Fudan University was interested in studying some aspect of the generational effects of this migration. Some married couples migrate to the urban areas, but leave their children in the provinces with their grandparents. Others couples migrate with their children. In the former case, parents look forward to the time that the family can get back together, after the children have finished college and joined them. In the latter case, the Chinese students were reporting that they never see their parents, since both are working all the time, and actually feel closer to their grandparents back in the rural provinces. Without the attention of their parents, many young people are getting involved with various delinquencies, such as drugs, alcohol, sex, and crime. The generation gap is thus exacerbated. To make matters worse, public education is funded at the province level, and municipalities like Shanghai are reluctant to provide education through high school for the children of migrants. These children, therefore, will have to return to the provinces for high school education, or drop out and enter the shadowy world of the informal economy.

Nevertheless, migrant workers are presenting significant challenges for the new urban economies. It is startling to me that every student who spoke to us at Fudan University was interested in studying some aspect of the generational effects of this migration. Some married couples migrate to the urban areas, but leave their children in the provinces with their grandparents. Others couples migrate with their children. In the former case, parents look forward to the time that the family can get back together, after the children have finished college and joined them. In the latter case, the Chinese students were reporting that they never see their parents, since both are working all the time, and actually feel closer to their grandparents back in the rural provinces. Without the attention of their parents, many young people are getting involved with various delinquencies, such as drugs, alcohol, sex, and crime. The generation gap is thus exacerbated. To make matters worse, public education is funded at the province level, and municipalities like Shanghai are reluctant to provide education through high school for the children of migrants. These children, therefore, will have to return to the provinces for high school education, or drop out and enter the shadowy world of the informal economy.

Of course, these generational migration problems would be occurring regardless of the one-child policy. But that policy highlights significant contradictory results in today’s China. Children born to urban families are “being spoiled.” Children born to migrant workers, on the other hand, are facing the difficult situation of being cast into the urban world with fewer controls on their behavior, and an uncertain sense of belongingness. Both cases are creating a cultural change large enough for attempts to legislate morality (to use an American political phrase), and will likely lead to greater individualism in a society that has long prided itself on a collective mentality.

Here is the address for my personal blog. It has pictures and my narrative from the ASA trip to China.

Listed here are excerpts of a few thoughts I recently posted on my own blog regarding the ASA trip to China… –John Green

Now it is time to think through all of things I learned about in China, and all of the questions I have. Here are some though sketches from the sociologist in me…

–China offers us an important case study for trying to understand the connections between economic growth, environment and health. On the one hand, with the rapid economic growth in the country, people’s material living standards have increased (on average that is) which is good for health in terms of access to better housing and caloric intake. On the other hand, the pace of growth has outstripped the willingness and ability of government to deal with the darker side of problems caused by heavy air and water pollution. As one of the world’s quickly rising economic powers, these are important issues not just for China but the rest of us as well. Who knows, in thinking through them, maybe those of us in the U.S. can learn something to take corrective action here at home.

–Transportation is an issue of immense importance in all societies, yet sociologists and other social scientists seem to be behind the curve in studying this issue. I know there are some people doing this work, but they are clearly not dominant within our fields. The importance of this really came to me while looking at the model of Shanghai and then reading a book about the environment in China on the plane ride home. Typically, the concern is with cars – the cost, needed infrastructure, congestion, time away from home, and the pollution. Also in need of attention are buses, trains and airplanes. Maybe most important to civilization is how we go about designing where education, work and services are provided in relation to where people live. We seem to take transportation as a given, but there are costs involved. These don’t just impact our pocketbooks as with the current gas price problems, but the environment and our health as well.

(The irony of reading a book about pollution on a plane burning thousands of gallons of fuel was not lost on me.)

–The massive rural to urban migration and associated dislocation and vulnerability of people in the lower socioeconomic spheres is an area of great importance. Luckily, many of the professors and students we met in China are concerned about this and directing their attention this way. We all need to be considering the patterns, forces at work and implications of these changes. We went through some of this in the U.S., and have learned somethings worth sharing. Now, of course, there are differences as population movements take place internally, internationally and even globally. How does this impact education, the workforce and provisioning of social and health services?

–All in all, these issues beg us to give more attention to concepts of social development and sustainable development.–

Symbols are everywhere and important in contemporary China – the buildings placed precisely on the meridian extending from the ancient Forbidden City, the representations of status hierarchies in all the monuments, the numbers and colors that have well-understood meanings, the construction of 55 huts in Olynpic Village to represent the 55 ethnic minorities in contemporary China. In my sleepy haze as we rode to our hotel from the airport, I noticed a rainbow arch over the road. Its colored lights extended from both ends, but did not join in the middle. Later in the trip I saw a second such arch. On the last day, I remembered to ask our guide about the meaning of this construction. She explained that the rainbow will remain unjoined until Taiwan is reunited with the Mainland.

If one visits China with images of a tightly controlled rule-bound society, one is quickly disabused of such notions. There is near anarchy on the roads and in public places. It takes courage to cross the street in China because crosswalks and traffic lights appear to be merely suggestions for the drivers. Drivers take the arts of aggression to heights unseen in the U.S. The concept of the queue is virtually nonexistent in public places. Bus companies employ people to organize and shepherd people onto the buses. Behavior in museums and restrooms is similarly unrestrained – from the student who leaned her notebook on the glass display case, thereby blocking everyone else’s view, to the women who entered the restroom and went straight to the front, ignoring the Americans who had organized themselves into a queue. That rules exist to be broken was also indicated by the wink and the nod given to ignoring prohibitions against photography and to the oft-repeated aphorism that “heaven is high and the emperor is far away.” The general idea appears to be that corruption is endemic and people are always susceptible. In ancient times, the Emperor employed eunuchs to avoid competition for his concubines and he dared not leave the palace for fear of a coup. In recent times, the 10-point bonus given to superior athletes on the national university entrance exam had to be eliminated as more and more overweight and unathletic young people had certificates as marathon champions.

Some aspects of life in China were incredibly familiar. I was amused to learn, for example, that sociology undergraduates at Fudan University in Shanghai complained that they shouldn’t have to learn statistics. I was less amused to hear that internal migrants were viewed with hostility: the areas where they live were viewed with disgust by local resident for their poverty and crime and the local authorities do not want to use their funds to support the education of the migrants’ children.

Ironies abound too. If we in the United States are often critical of Walmart for not giving workers adequate health insurance, how interesting it is that in the People’s Republic of China, health insurance serves as an inducement for workers to take jobs at Walmart. Elites in the PRC hope that the next U.S. Administration will be Republican because they fear that Democrats might place restraints on world trade. Despite the real fears that the aged are no longer adequately cared for by their children (one local area was considering legislation that would mandate that children maintain regular contact with their parents!), the retirement age is 55 for women and 60 for men. Nevertheless, senior discounts are offered only to people over the age of 70.

One fascinating moment in our meeting with sociology faculty and students: a graduating senior noted that Americans she encountered always ask about the democratization of China. “Do they really care,” she wondered. Her own concerns and those of her fellow students were more mundane, she explained. They worried about getting good jobs, for example.

Finally, it is hard to describe the awe with which this New Yorker viewed Shanghai. Not only have they managed to build some 4,000 high-rise buildings since 1990, but they have managed to make them architecturally fascinating by employing well-known architects from around the world. It is unbelievably impressive.