Doug Hartmann: There are at least two facets of religion in America that stand out to sociologists. First, Americans have long been among the most religious people in the developed world. Religion has been a foundation of community, connection, and citizenship throughout this country’s history. Second, there is a remarkable diversity and pluralism of religious belief and practice in the United States, documented most recently and famously by Diana Eck‘s religious pluralism project at Harvard.

Few nations can claim this unique combination; typically, religious devotion goes hand in hand with religious conflict (or worse). Indeed, it is precisely because of this harmonious combination of devotion and diversity that noted political scientist Robert Putnam (he of Bowling Alone fame) titled his recent book on American religion American Grace.

For a sociologist, this unique, almost paradoxical combination of devotion and diversity raises questions about solidarities and boundaries. These kinds of questions inspired me to undertake a research project with some of my students almost a decade ago on the idea of America as a Judeo-Christian (rather than Christian) country. Without going into the details, we found that over the course of less than 50 years, the term “Judeo-Christian” went from being either a cultural curiosity or political provocation to a bipartisan, mainstream touchstone supposedly signaling the historic culture of the nation.

As Wing Young Huie and I started talking about religion and society, I remembered this paper and sent it along. Wing is not particularly religious, though he was for some time, and I don’t know how closely he read my paper or what he thought of it, but this is the photograph and commentary he sent in return.

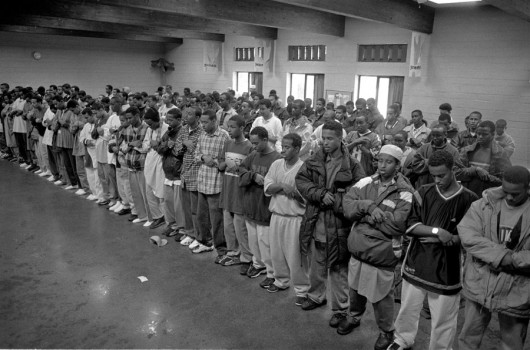

Wing Young Huie: When I took this photograph in 1998, nearly half of the student population at Roosevelt High School, located in the urban core of South Minneapolis, was Somali. Perhaps school district officials thought it best to keep all of the refugees together; that’s what they’d done with Southeast Asians in the mid-‘70s, too.

All of the students pictured here are Muslim and, as required by their faith, pray five times a day. This could be problematic during school hours, and they’d pray as discreetly as they could under stairwells or in bathrooms. Whether it was the separation of church and state that legally prohibits prayer in schools or the distinctly not Christian spectacle of prostrated Islamic worship, the Somali students banded together to find an alternative place to pray. Racial tensions flared between these students and both white and other black students at Roosevelt.

Ironically, Our Redeemer Lutheran Church (across the street from the school) became the safe haven for these kids. Every Friday during their lunch hour, Somali students transformed the basement of Our Redeemer into a mosque. First the boys prayed, then the girls.

Fourteen years later, I wondered if a Muslim prayer group still meets. I was surprised to see that the church marquee now reads: Our Redeemer Oromo Evangelical Church. The cultural cross-pollination continues: the Oromo, ethnic refugees from Ethiopia, now occupy the sanctuary and hold services in both Oromo and English (for the young Oromos who don’t speak the mother tongue). The Roosevelt Muslim student group is still going strong and has moved its services several doors down to the YMCA. One school administrator told me that they are now joined by a significant African American contingent that has converted to Islam.

Doug Hartmann: At first, I was surprised by Wing’s choice of an image. But as I started thinking it through, I came to see Wing’s representation of Muslim men as a wonderful commentary on the ongoing changes, challenges, and complexities of the cultural-religious core of American cultural life. The photo and Wing’s commentary underscore both how open and tolerant Americans can be of religious differences, as well as of how much work we still have to do in terms of acknowledging, accepting, and incorporating these different communities of believers. I mean, on the one hand, if there is some big, cultural consensus about America being a Judeo-Christian nation, where does this leave Muslim Americans? Apparently, sometimes in stairwells and basements. I’m quite sure that this is why some conservatives are so obsessed with the belief that our President, whom they cannot stand, is secretly Muslim.

More interestingly, I went back and reviewed my original paper. There I was equally surprised (and a bit embarrassed) to be reminded that we had actually found that Muslims and Islam were at that time emerging as a major point of discussion and controversy in the context of references to Judeo-Christian culture. I couldn’t believe I’d forgotten this thread and needed Wing to help me rediscover it! Now I’m thinking it might be time to update this research, originally undertaken early in the new millennium, when the after-effects of 9/11 and its implications for Arabs and Muslims and Islam were only beginning to be felt.

Comments 7

kat — May 1, 2012

" I mean, on the one hand, if there is some big, cultural consensus about America being a Judeo-Christian nation, where does this leave Muslim Americans? "---it leaves them in the same place as the Jews. This "Judeo-Christian" hyphenation is imposed by the majority Christians on a minority "Judeos" without a "by-your- leave"---the few Jews I have spoken with (on the net)do not appreciate being hyphenated to Christianity!!! studies show no abation in anti-Jew hate crimes and instead show a link between anti-Jew bigotry, prejudice, and hate to anti-Muslim hate.

Pretty phrases like "Judeo-Christian" can perpetuate a fantasy that hides an ugly truth.............

Letta Page — May 2, 2012

You know, Kat, I think the interesting part is that Judeo-Christian is, in many ways, based on the commonality many Jews and Christians find as monotheists who are often quite culturally similar in the U.S. (this is clearly excluding the more fundamentalist or Orthodox of both religions who conscientiously choose a lifestyle that sets them apart from "mainstream" America - a phrase that's fraught on its own). Anyhow, the monotheistic base would seemingly be extended to include Muslims, as Islam is the third major monotheistic world religion, and yet they continue to be viewed as suspicious outsiders, even when they're, say, converted Muslims or American-born Muslims. I'd be interested in the studies you've cited that show a continuation of anti-Seminitic hate crimes in the U.S. and how they might be curtailed by not pointing out commonalities among believer groups.

Of course, one does have to realize that any conversation of this sort will naturally spring out of one's own experience. I, personally, was baptised as a Lutheran, raised by an Atheist and a Jew (and since that Jew is my mother, I am considered culturally Jewish and did attend Hebrew school for a short time), and, as an adult, identify as a practicing Buddhist.

An amusing side-note: when called upon to explain Islam to my 8 year old nephew, I did my best to give an overview of monotheism and the ways in which they are all interconnected, the baseline is to care for children, the elderly, and the poor, etc. He listened carefully, then paused and asked, "But what's a Hobo's Witness?" :) It's always good to keep talking about others and their own religions, religious identifications, and cultural markers. For me, Judeo-Christian is actually a great step in the direction of not identifying all Americans as Christians, but I'd reckon the country is actually more of a secular monotheistic country; and even that excludes me!

Thanks, as always, for joining the TSP conversation.

REW — May 3, 2012

Jews were also considered a suspect religion in America for a long time. In fact, I have always felt that the Muslims have become the Jews of the 21st century--a religious group persecuted and scapgoated simply for being who they are.

doug hartmann — May 3, 2012

Very interesting comments and interpretations here, and i've got another observation to throw into the mix. On the advice of a friend and colleague in town (not a sociologist), i've just been reading Sumbul Ali-Karamli's "The Muslim Next Door: The Qur'an, the Media, and that Veil Thing" (White Cloud Press, 2008). It is a book whose goal is to introduce Americans to Islam and provide a window into the experience of living as a Muslim in America. It is a provocative, easy-to-read volume by an author who is earnest, eager to be liked, and simply hoping to have her people and faith understood and accepted. Anyway, one of the first chapters is entitled: "Some Basic Islamic Concepts and How Islam Fits into the Judeo-Christian Tradition."

Ellen Fee — October 12, 2012

The story of the Lutheran Church opening up its doors to the students really epitomizes, at least to me, what religion should be about--tolerance, acceptance, being willing to lend anybody a helping hand. Just because a person is one religion should not mean they are against anyone who dares be different from them. In reality, America cannot be defined as a Judeo-Christian nation. It is a Judeo-Christian-Athiest-Muslim-Mormon Nation, plus so, so many other practices, but that's the point--America shouldn't, and I think cannot, be defined by the religious practices of its citizens.

Ellen — December 13, 2012

I find it interesting that the piece begins by discussing the plurality of American religions, yet in the paper, it only talks about the three dominant monotheistic religions. If this was truly a discussion on how more obscure religions fit into the map of Judeo-Christian culture in America, it would not be discussing a religion that has many similarities to both religions. A true discussion of difference would acknowledge other religions like Wicca or the Amish who have also managed to find a niche within American Culture. A discussion of Muslims assimilating without a discussion of the implications of 9/11 and the irrational fear of Islam that arose from it, destroys any chance argument of difference.

While I appreciate the author avoiding the old debate of how 9/11 affected perceptions of Islam, without this debate, his argument seems pointless because of the similarities in religion. The fact that a monotheistic religion found a niche in a predominantly monotheistic american society, is not shocking or new, the fact that they continued to be accepted after the suspicions and questioning of their values and religion is more impressive. A debate about Islam in America without the discussion of 9/11 is not a discussion of difference values, but a difference of practices.

Look what I found | Miscellany101's Weblog — September 28, 2014

[…] ran across this picture here. It was taken in 1998 in South Minneapolis and it is a group of Somali students praying at Our […]