Reposted with permission from the Texas Population Research Center

Approximately one-third of women and one-fifth of men aged 60 and over in the U.S. live alone and are at heightened risk of social isolation due to social distancing and other safety precautions introduced to curtail the spread of COVID-19.

A national study conducted in 2015 found that among older adults, in-person contact was associated with lower levels of depression, but telephone or electronic contact were not. Research is mixed about whether social distancing due to COVID-19 leads to older people feeling more lonely. For example, one study found that in February 2020, older Americans who lived alone reported more loneliness than older adults who lived with others. However, there was no increase in reports of loneliness during the stay-at-home orders. Another study of Germans found that older adults reported less loneliness than younger adults, regardless of whether they lived alone or with others during the pandemic.

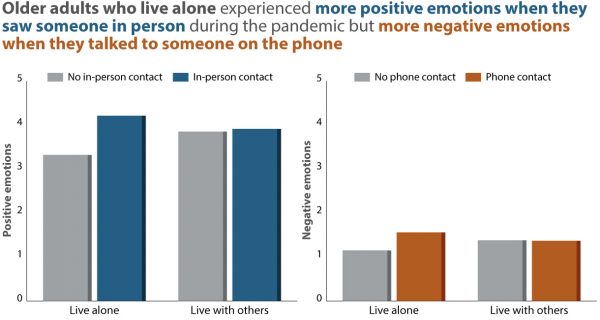

This brief reports on a recent study which examines how daily positive emotions (gratitude and contentment) and negative emotions (loneliness, sadness, and stress) vary based on whether people live alone during the pandemic and who they encountered throughout the day.

The authors surveyed 226 people aged 69 and older living in the Austin, Texas area during May and June 2020. The older adults reported on their living situation, social contact (in person, by phone, electronically) with different social partners, and emotions during the morning, afternoon and evening the prior day. Of those surveyed, 81 lived alone and 145 lived with spouses, family or other people. Nearly all the older adults were taking safety precautions, sheltering in place and avoiding contact with people outside their home.

Key Findings

- Older adults who live alone were, unsurprisingly, less likely to see others in person or to receive or provide help than those who lived with others. Contrary to expectations, those who live alone did not report more time on the phone or using electronic communication, such as text, email, or use social media.

- Older adults who live alone experienced more positive emotions when they saw someone in person compared to those who had no in-person contact (see Figure, left panel).

- In contrast, older adults who live alone experienced more negative emotions, especially loneliness, when they talked to someone on the phone (see Figure, right panel). This may be because talking to others by phone may remind people of their feelings of being alone during the pandemic.

- Older adults who live alone were more likely to have contact with friends, rather than family.

- Among older adults who live with others, contact with others – in person or by phone – did not affect positive or negative emotions throughout the day (see Figure).

Note: See published paper for confidence intervals for all results.

Policy Implications

These findings suggests that in-person contact may confer unique benefits to positive emotional well-being. In other words, technologically-mediated communication cannot replace the physical presence of others. Those who want to support emotional well-being in older adults who live alone with in-person contact should do so while following COVID-19 safety guidelines, such as limited contact with other individuals who are also sequestering, keeping that contact at a distance of at least 6 feet, visiting outside and mask wearing. Because phone calls for older adults who live alone may increase feelings of loneliness, older adults may want to schedule phone calls for days they may also see a friend in person from a distance and while wearing a face mask. Friends and relatives who telephone also might set up the next phone call when they finish to remind the older adult of ongoing contact.

Reference

Fingerman, K.L., Ng, Y.T., Zhang, S., Britt, K., Colera, G., Birditt, K.S., & Charles, S.T. (2020). Living alone during COVID-19: Social contact and emotional well-being among older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Social Science. Published online ahead of print.

Suggested Citation

Fingerman, K.L., Ng, Y.T., Zhang, S., Britt, K., Colera, G., Birditt, K.S., & Charles, S.T. (2021). Older adults who live alone benefited from seeing people in person during the pandemic but not necessarily by talking on the phone. PRC Research Brief 6(1). DOI: 10.26153/tsw/11348.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants R01AG046460 and P30AG066614 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and grant P2CHD042849 awarded to the Population Research Center (PRC) at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Karen L. Fingerman (kfingerman@austin.utexas.edu) is a professor of human development and family sciences a faculty research associate in the Population Research Center, and director of research of the Center on Aging and Population Sciences, all at The University of Texas at Austin; Yee To Ng and Shiyang Zhang are PhD students in human development and family sciences at UT Austin; Katherine Britt is PhD student in nursing at UT Austin; Gianna Colera is a master’s student in professional counseling at Texas State University; Kira S. Birditt is a research associate professor at the Survey Research Center and director of the Aging and Biopsychosocial Innovations Program at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; and Susan T. Charles is a professor of psychological science and nursing science at the University of California at Irvine.