Imagine trying to juggle a career and family life without a reliable safety net—this is the reality for many parents, especially mothers, in the U.S. Finding affordable, dependable, and high-quality childcare can feel like searching for a needle in a haystack.

The COVID-19 pandemic made things worse. Two-thirds of childcare centers had closed by April 2020, and one-third remained closed in April 2021. With childcare centers and schools closed, many parents struggled to work from home while caring for their children. Many other parents who did not have the option to work from home had to quit their jobs due to childcare needs. This was particularly tough on mothers and families with fewer resources.

Families usually turn to informal sources of childcare, such as babysitters/nannies, extended family members, older children, friends, neighbors, or in-home group childcare when formal childcare is disrupted. However, the pandemic made it harder for some families to access these options than others. COVID-19 disproportionately affects older populations and people of color, and families of color disproportionately relied on older relatives for childcare before the pandemic. This left many families, especially those with limited financial resources, struggling to find the care they needed.

When the pandemic upended formal childcare, who stepped in to help U.S. families? And how did these shifts affect parents’ work hours? We examined these questions in our recent research published the Journal of Family Issues. Our study was based on data from a nationally-representative survey of 1,954 U.S. parents. The Institutions Trust and Decisions Study was conducted online from November 30 through December 30, 2020 on Qualtrics by researchers from Indiana University.

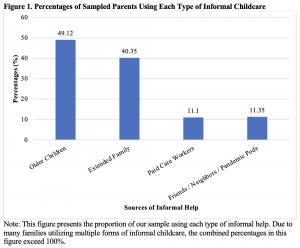

We found that 60% of U.S. parents received informal childcare help during early stages of the pandemic. Notably, care provided by older children emerged as the most common form. Around 50% of parents relied on older children as caregivers. About 40% of parents received help from extended family members. These patterns were likely facilitated by the shift to remote instruction, which left older and younger children at home together during the day, even if their parents had to leave home to complete their paid work. Our finding suggests that childcare help from older children was at least as important as extended family childcare, which has been the main focus of prior studies on informal childcare.

Secondly, families from different socioeconomic backgrounds differ in terms of the kinds of informal care they used. Parents with at least a college degree and those with family income above $150,000 were most likely to have received informal help, especially from paid care workers. Latinx, and other/multiracial families were less likely to use paid care workers than White families.

Finally, receiving support with informal childcare potentially helped parents with young children, especially mothers who lost or left their jobs during the pandemic, work more hours. More flexible forms of informal childcare, such as care provided by older children, extended family, neighbors, friends and pandemic pods, was especially important in helping these mothers work more hours.

Our research reveals a stark divide: low-income, less-educated, and families of color, especially mothers with young children, faced major childcare hurdles during the pandemic. Meanwhile, wealthier and White families often had the means to secure the few available paid caregivers. To keep disadvantaged families in the workforce, we must support them better. Policymakers should recognize and assist the unsung heroes—grandparents and older children—who stepped up as informal caregivers despite facing heightened health risks and stress during such crises. Remarkably, older siblings often took on the role of caregiver, balancing schoolwork and the responsibility of looking after their younger brothers and sisters. These young caregivers played a crucial part in helping their families navigate the challenging landscape of the pandemic.

Milly Yang is a PhD Candidate in Sociology at Yale University. She can be reached at milly.yang@yale.edu. Twitter: @MillyYYang.

Emma Zang is an Assistant Professor of Sociology, Biostatistics (Secondary) and Global Affairs (Secondary) at Yale University. She can be reached at emma.zang@yale.edu. Twitter: @DrEmmaZang.

Jessica Calarco is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She can be reached at jcalarco@wisc.edu. Twitter: @JessicaCalarco.

Comments