In May 2022, Johnny Depp fans heckled Amber Heard and called her a “gold digger” as she left the courthouse in her defamation trial. Depp also called her a gold digger during her 2020 libel trial. Accusations of gold digging in one of the most publicized celebrity conflicts of the twenty-first century is not an accident, and this seemingly minor insult carries tremendous baggage. The history of the “gold digger” stereotype—and its power to shape perceptions of romance, marriage, and family—deserves our close attention.

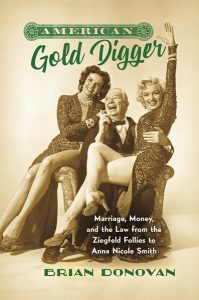

The term “gold digger” refers to women who pursue romantic relationships for financial gain. To be sure, men have sometimes been accused of being gold diggers but, over the last century, it’s a label overwhelmingly applied to women. From its origin as chorus girl slang in the early 1900s it grew as a popular misogynistic slur. My book American Gold Digger: Marriage, Money, and the Law from the Ziegfeld Follies to Anna Nicole Smith (University of North Carolina Press) traces the history of the gold digger stereotype in the twentieth century. The book shows how depictions of gold diggers distort the conditions surrounding courtship and marriage. Alleged gold diggers absorb blame rightly directed toward structural and historical forces.

Moral panics about gold diggers emerged when American families experienced rapid social change. During the worst years of the Great Depression activists led a campaign to outlaw breach of promise litigation, a legal remedy available to women who were betrayed by their potential suitors. Inside movie theaters, millions of Americans watched stars like Mae West and Joan Blondell portray gold diggers who used so-called “heart balm” laws to con gullible men out of their hard-earned money. Inside courthouses and statehouses, crusaders successfully eliminated breach of promise laws (despite a steady decline in breach of promise lawsuits since the late-nineteenth century). What was once embraced as a remedy to restore a woman’s good name in a cutthroat marriage market now was regarded as a tasteless ploy from lower-class women to marry above their social station. The anti-heart balm campaign drew strength from popular representations of gold diggers, and gold digger narratives created a ready-made scapegoat for economic struggles.

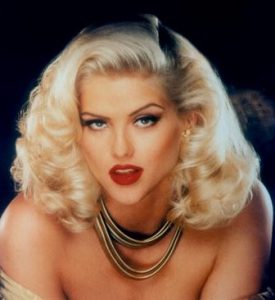

In the 1990s, the American public fixated on the marriage between Anna Nicole Smith, a twenty-six-year-old model, and J. Howard Marshall, an eighty-nine-year-old oil tycoon. After Marshall’s death, his son and Anna Nicole Smith fought over the multi-million-dollar Marshall estate, a decade-long battle that involved two trips to the Supreme Court. During these years, the media’s characterization of Smith as a gold digger destroyed her reputation as a path-breaking fashion model. She became a joke in popular culture, with headlines that referenced popular gold digger movies from the 1950s. Few questioned Marshall’s wealth, evidence of his alleged involvement in criminal tax avoidance, or his connection to far-right figures like the Koch brothers. Marshall was remembered as a victim. Smith was remembered as a punchline. The gold digger trope worked its social magic. Complex legal and economic issues were simplified. Blame and anger were redirected toward an allegedly greedy woman.

For the past 100 years the gold digger trope has allowed structural problems confronting American families to be seen in an individualized, personalized, and stylized way. The effects of legal and economic change on American families are often hard to grasp, but the gold digger is an easily accessible and understandable figure. The durable popularity of the gold digger trope shows how law and popular culture merge together to create powerful stereotypes that have lasting consequences.

Brian Donovan is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Kansas and current President of the Midwest Sociological Society. Donovan is the author of White Slave Crusades, Respectability on Trial, and American Gold Digger. He can be reached at bdonovan@ku.edu. Donovan (and his cats) can also be found on Twitter at @golddiggerbook.

Comments