At wedding showers, guests are often asked to provide advice to the newlyweds. As someone who values my alone time, one of my favorites has always been, “The key to a happy marriage is spending lots of time apart.” But for many married couples in the US in March 2020, “spending lots of time apart” became unattainable due to workplaces, schools, churches, restaurants, gyms, and other public or semi-public spaces closing their doors. Other couples—in which one or both spouses worked “essential” jobs with high risks of COVID-19 infections—contended with very little time together. At the same time, although shutting down public gathering spaces and public health officials cautioning against social interactions outside of households was clearly beneficial to reducing the spread of COVID-19, it also likely posed unique risks for the mental health and social well-being of single adults, especially those who lived alone or provided care to children and other family members.

These complex dynamics point to a likely reality: Families have been especially salient for our health and well-being during the pandemic period. Family scientists have long shown that family status—including relationship status—is linked to health, with most studies finding (broadly speaking) that married adults have better health outcomes than never married, divorced, and widowed adults. Yet these patterns, like all social science patterns, are context-specific, and studies are only beginning to consider how this may have shifted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

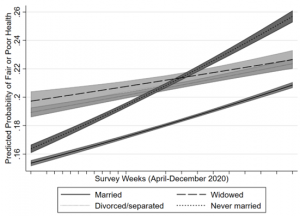

To address this, in my recent study (2022), I analyzed survey data from April to December 2020. I found that never married respondents had increased probabilities of fair or poor health, depression, and anxiety relative to married adults as the pandemic progressed. The dominant ideology within the US even before the pandemic privileged marriages and legal families, as reflected in public policies such as people having access to their spouse’s employer-based health insurance and “greedy marriage” norms which encourage married couples to prioritize their spouse above other relationships. The pandemic may have amplified this social advantage for the married, as the pandemic period was generally characterized by increased reliance on families—giving adults with a spouse a potential health-related benefit. Spouses likely provided important financial and practical support for each other in the context of unstable employment and childcare and emotional support while navigating the death and illness of loved ones and uncertain social times. Given limited opportunities to gather and socialize outside of the household, single adults who lived alone may have had less access to these supports. These dynamics together for never-married and married adults perhaps underlie the patterns I found in my survey analysis of widening health disparities for these two groups.

Yet I also found a narrowing of the difference in health outcomes for married compared to previously married adults over these same months, demonstrating the need to disentangle groups of non-married adults and not treat the “marital advantage” as universal. Although these survey data did not allow me to examine marital quality, other studies have shown that relationship strain increased as the pandemic progressed. Being isolated together as a couple—alongside new financial and health stressors—may have increased tension within relationships. Additionally, many couples experienced conflict around discordant views on masks, social distancing, and (in later months) vaccines. As an additional caution against seeing marriage as universally beneficial for health during the pandemic, my analysis further showed that marriage was more meaningful for men’s mental health than women’s, in line with feminist understandings of his and hers heterosexual marriages where men and women in the same marriage experience starkly different dynamics and benefits.

Figure: Estimated Trends in Reporting Fair or Poor Health by Relationship Status, Household

Pulse Survey, April-December 2020

Note: N=1,422,733. Weighted. Models adjust for gender, race/ethnicity, age, educational attainment, household income, coresidential children, and pandemic-related stressors (lost income, food insufficiency, delayed medical care, and issues with paying for housing).

The patterns I showed in this analysis are not inevitable but rather reflect the public policies and organizational decisions across the pandemic months. Health disparities, including family-based health disparities, are not static, but dynamic—shifting alongside changes within society. During the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, public policies were created to specifically strengthen the social safety net, including changes to unemployment benefits, stimulus payments from the federal government, and protections against evictions and debt repayment. Yet rather than extending these policies, many expired after a short period of time, likely to the detriment of the most vulnerable within society and resulting in strains on families and individuals. Within the current environment, married couples are generally at an advantage because society privileges marriage above friendships, siblings, cohabiting and dating relationships, and other social arrangements. We should aim to create policies that support multiple types of family arrangements beyond marriage, recognizing the multiple forms and functions that families and communities take, and in turn reduce disparities across these diverse family types—not broaden them.

Mieke Beth Thomeer, PhD is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and a Deputy Editor at the Journal of Marriage and Family. Follow her @miekebeth

Comments 1

shialu — December 8, 2025

Good info indeed