A briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families’ Symposium Parents Can’t Go It Alone—They Never Have.

If debates about women’s rights, relationships between the sexes, and worsening conflicts between paid work and family life seem endless, that’s because Americans can’t agree on what is happening, much less on what to do about it. Some blame the problems on a “gender stall,” as women continue to hit glass ceilings at work and perform the lion’s share of caregiving at home. Others focus on the decline of men’s breadwinning as their earnings erode, their labor force participation drops, and they fall behind women in educational attainment and career aspirations. Progressives lament the lingering traditionalism that leaves women mired in second-class citizenship, while conservatives worry about the rise of a self-centered individualism that elevates personal freedom over lasting commitments to others.

To gain a more nuanced picture of how today’s adults are negotiating work–family conflicts, I conducted face-to-face depth interviews with 120 (self-identified) women and men between the ages of 33 and 47 years—the years when most Americans face their peak challenges in building both their work and their family lives. I went to two different geographic areas, interviewing people living in the heart of the “new economy” in Silicon Valley (stretching from San Jose to the East Bay) and those living in or near America’s biggest city, the New York metropolitan area. This approach yielded a group with diverse racial, economic, and educational backgrounds living in a variety of family arrangements, including singles, cohabiters, and married couples.

My interviews revealed four major patterns of response to the challenges of earning a living and caring for others. At one end of the spectrum, one-fifth of my participants adopted a “hyper-traditional” pattern that emphasized overwork for fathers and intensive parenting for mothers. Concerns about job security prompted husbands to put in very long work weeks (ranging from 60 to as many as 100 hours) to assure employers of their work commitment. In a parallel way, concerns about living up to a standard of “intensive parenting” left wives with equally strong pressures to devote their utmost attention to childrearing. Although these mothers and fathers felt overworked in their separate spheres and deprived of both personal time and time together as a couple, they did not believe they could risk doing anything else.

At the other end of the spectrum, 24 percent opted to remain “unencumbered.” These adults remained single and childless or became estranged from offspring in the wake of a breakup. A comparable percentage of women and men followed this path, but they did so for different reasons. The men were typically unable (or unwilling) to find steady work and concluded they could not afford to take on the financial or emotional responsibilities of marriage and parenthood. The women found they valued work too much to dilute their career commitment by taking on commitments to care for husbands and children.

In a very real sense, the hyper-traditional couples are recreating traditional gender patterns in an especially extreme form, whereas the unencumbered are opting to preserve their independence by avoiding such traditional family commitments. Yet together these two extremes account for only 44 percent of my respondents. The remaining 56 percent comprises two additional groups.

About a quarter (26 percent) of my participants are in relationships that reflect the simultaneous decline of the male breadwinner wage and the persistence of the female caregiver norm. These families rely on the woman’s earnings as much as they do on the man’s (and sometimes more) but they also depend on her for the bulk of caregiving. In these cases, women do not “have it all” so much as they “do it all.” It is hardly surprising that carrying the load as both a primary or co-breadwinner and the main caretaker leaves most of these women feeling tired, disheartened, and unappreciated—but they are not alone in their frustration. Most of the men in these relationships also express frustration, saying they wish they could do more caregiving, but fear that taking the necessary time would endanger their job security and prospects. What’s more, these are not unrealistic fears. Research has demonstrated that a “flexibility stigma” penalizes workers—especially professional men—who choose to pull back even slightly to engage in care work at home.

The remaining 30 percent of my participants can be described as egalitarians—couples who are experimenting with building an equal partnership despite the obstacles. With no clear path to follow, they do so in varying ways and with varying degrees of success. A third of this group (about 12 percent of the entire sample) decided to avoid the difficulties of equal caretaking by forgoing parenthood altogether, with many looking to relatives, friends, and pets for other forms of caregiving ties. The rest were willing to limit their working time, risk their financial prospects, and forego sleep and personal time to try to divide work and caregiving equally. Yet the dearth of institutional supports has left many of the work–care egalitarians wondering how long and at what cost they can sustain their efforts.

Despite their differences, all these strategies are responses to a similar set of pressures and conflicts. Rising job insecurity has upped the ante for workers, forcing them to put in long hours or risk losing their employment or endangering their future security. On the home front, concerns about rising inequality and declining social mobility have upped the ante on childrearing, creating a sense that only intensive parenting can prepare children to navigate an uncertain future.

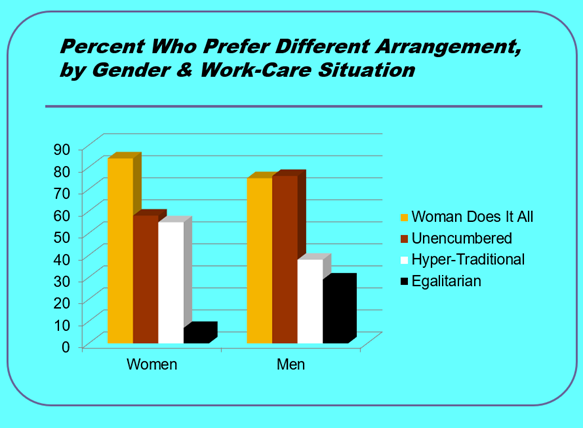

Each of the four strategies described inevitably produces some degree of dissatisfaction, but the one commonly seen as most challenging—that is, the egalitarian strategy—turns out to be most preferred by those who practice it. Figure 1 shows that 55 percent of hyper-traditional women and 38 percent of hyper-traditional men would prefer a different arrangement, while 84 percent of the women who “do it all” and 75 percent of men who rely on a woman to do it all would also prefer a different arrangement. Among the unencumbered, 58 percent of women and 76 percent of men report that a different situation would be preferable. In contrast, those expressing the lowest desire for a different arrangement are the egalitarians, with only 7 percent of women and 29 percent of men saying they would prefer one of the other alternatives.

Each of the four strategies described inevitably produces some degree of dissatisfaction, but the one commonly seen as most challenging—that is, the egalitarian strategy—turns out to be most preferred by those who practice it. Figure 1 shows that 55 percent of hyper-traditional women and 38 percent of hyper-traditional men would prefer a different arrangement, while 84 percent of the women who “do it all” and 75 percent of men who rely on a woman to do it all would also prefer a different arrangement. Among the unencumbered, 58 percent of women and 76 percent of men report that a different situation would be preferable. In contrast, those expressing the lowest desire for a different arrangement are the egalitarians, with only 7 percent of women and 29 percent of men saying they would prefer one of the other alternatives.

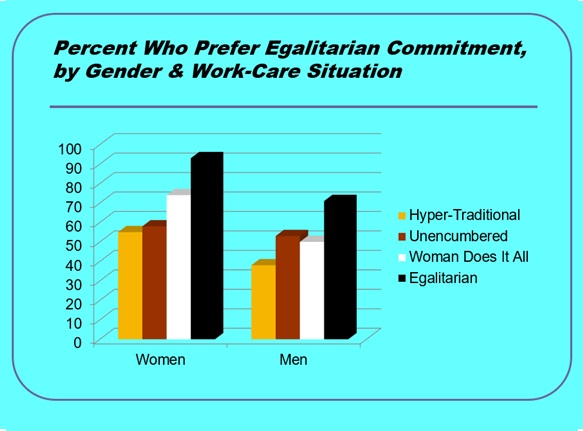

What arrangement do people prefer? Figure 2 shows that in addition to the egalitarians, where 93 percent of women and 71 percent of men prefer their situation, most of the rest of my interviewees also would prefer to share breadwinning and caregiving in an egalitarian way if that were a more realistic option. Women are understandably more likely to prefer sharing, with 74 percent of those currently “doing it all,” 58 percent of the unencumbered, and 55 percent of those in hyper-traditional relationships preferring more equal sharing. Although men expressed less enthusiasm for sharing, a significant minority—including nearly a third of hyper-traditional men, almost half of men who rely on a woman to do it all, and slightly more than half of unencumbered men—expressed a preference for an egalitarian partnership.

What arrangement do people prefer? Figure 2 shows that in addition to the egalitarians, where 93 percent of women and 71 percent of men prefer their situation, most of the rest of my interviewees also would prefer to share breadwinning and caregiving in an egalitarian way if that were a more realistic option. Women are understandably more likely to prefer sharing, with 74 percent of those currently “doing it all,” 58 percent of the unencumbered, and 55 percent of those in hyper-traditional relationships preferring more equal sharing. Although men expressed less enthusiasm for sharing, a significant minority—including nearly a third of hyper-traditional men, almost half of men who rely on a woman to do it all, and slightly more than half of unencumbered men—expressed a preference for an egalitarian partnership.

These findings make it clear that although every work–care strategy poses significant trade-offs and difficulties, people should not be forced to choose between hyper-traditionalism and hyper-individualism. Given the realities of the new economy, which relies on women workers but rarely longer offers job security to anyone, regardless of their gender identity or class position, it is neither humane nor just to confine the measure a man’s worth to his ability to be a successful breadwinner or a woman’s worth to her willingness to be a selfless caregiver. The solution is not to shore up and intensify an outdated system, but to address the inequalities and insecurities that permeate the current one.

How can we get to a more reasonable future? The first step is to reframe the work–care debate. It is time to jettison the tired lens of “having it all”—a lens that sees earning and caregiving as incompatible goals and the people (read women) who seek it as selfish or unrealistic. Instead, it is time to build our work and caring institutions on the principles of gender justice and work–care integration. Concretely, this means regulating time norms at the workplace so no worker must choose between excessively long work weeks and job insecurity. In our communities, it means creating caretaking resources that extend beyond the privatized household for children of all ages. And in our political institutions, it means ensuring equal economic opportunities for women of all stripes, equal caregiving rights for fathers as well as mothers, and a strengthened safety net that provides everyone with the basics that fewer and fewer jobs provide, such as a livable income, decent health care, and access to supports for weathering the ups and downs of our increasingly uncertain economic and family lives.

The rise of the new precarious economy is as challenging as the rise of the industrial system was more than a century ago. This transformation calls for structural and cultural realignments as vast as the shifts they need to address. Judging from the responses of my informants, the costs of doing nothing are far greater than the costs of helping everyone—women and men alike—forge a more balanced, equal, and secure division of work and caregiving.

Kathleen Gerson is Professor of Sociology, and Collegiate Professor of Arts and Science at New York University, Kathleen.gerson@nyu.edu.

Comments