In today’s labor market, women earn about 80% of men’s wages. This statistic and discussions of gender equity in pay have been covered by the media with renewed force in recent months, in part sparked by the U.S. women’s national soccer team suing the U.S. Soccer Federation for gender discrimination relating to unequal pay in March 2019. What factors contribute to the gender wage gap? Some argue that the time women spend out of work and the work lapses they experience for family and caregiving reasons explains part of the gender wage gap—that is, among other factors, the different employment trajectories men and women experience over the life course is one roadblock in reaching gender wage equality.

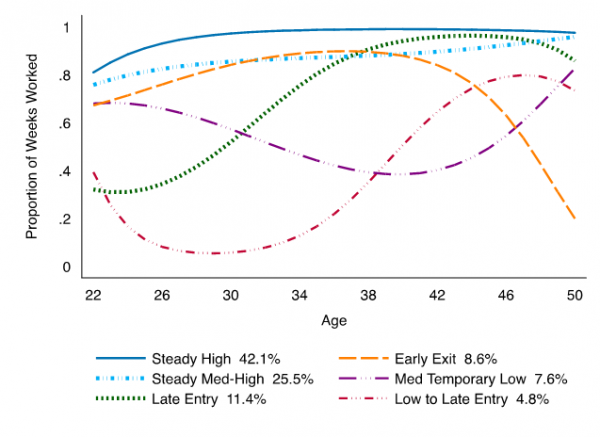

We investigate the linkage between employment trajectories and the gender wage gap in a forthcoming article in Demography. Using national data of the work histories of more than 6,000 individuals (NLSY 1979), we first identify six different employment trajectories from ages 22 to 50 (see Figure 1). We find that men’s and women’s levels of work attachment over the life course vary significantly; some follow steady work at high levels, others have low attachment to work either early or late in their careers, and some experience temporary declines in employment. Although steady employment trajectories are the most common overall; we find important gender, racial, and class disparities in the ability to secure steady work. For example, women are underrepresented in the group that follows a steady high level of attachment (36% are women), and women are more likely to experience low levels of employment either in the early career or temporarily around the late thirties. We also find that women across racial/ethnic groups and Black men are more likely than their counterparts to experience non-steady employment. Individuals who have experienced poverty are also at heightened risk of having lower and intermittent employment levels.

Figure 1. Employment trajectory groups of men and women across the life course

Source: NLSY 1979 data, from 1979-2014 surveys.

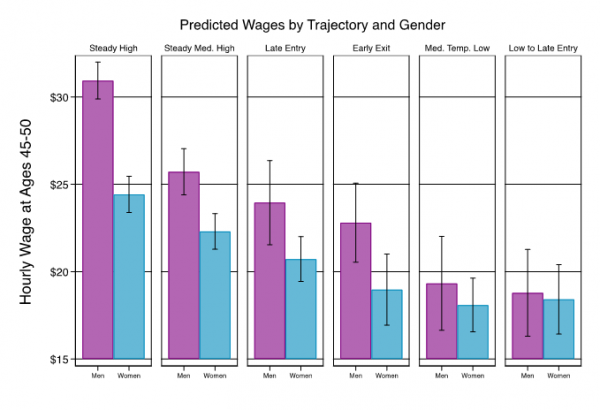

This analysis shows that relatively advantaged demographic and social groups are more likely to secure steady and high levels of work throughout their lives—which also have the highest wage pay off later in the career. We then ask: within employment trajectories—that have similar levels and timing of work attachment—how does the gender wage gap vary? We find that in the trajectory with highest levels of steady employment, the gender wage gap is the largest: among those who have steady and high levels of employment throughout their lives, women earn about 78.9% of men’s wages (see Figure 2). Men have higher wages than women across trajectories, but in non-steady paths this wage premium is reduced. In other words, men are relatively more penalized than women for not working continuously at high levels.

These findings suggest that even if women’s employment trajectories become more like men’s, the gender wage gap would remain persistent. This places women in a double bind; either they experience less gender wage inequality in low attachment trajectories, or access relatively higher wages in steady work paths that have a larger gender wage gap.

Figure 2. Predicted wages by trajectory and gender.

Note: The model includes a set of individual, family, and work characteristics. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

Why are men relatively more penalized than women for following non-steady employment trajectories? Non-steady and lower attachment paths are commonly associated with women who experience work lapses due to caretaking and family responsibilities. Employers might perceive men who follow these paths as violating breadwinning norms and expectations about what an ideal worker’s employment trajectory should be. Weisshaar’s recent article in American Sociological Review shows that in the hiring process, family-related work lapses are penalized relative to continuous work and even compared to unemployment spells. Both mothers and fathers who had family-related work lapses are penalized, but in highly competitive markets, fathers seem to fare worse. Fathers who had family-related lapses are also perceived to be less committed and reliable than mothers—suggesting that the role of employers’ preference could be a partial explanation of the reduced wage premium we find for men who follow non-steady employment trajectories.

Advancing towards equal pay will require cultural, policy, and workplace changes. Expanding work opportunities to create equal access to steady employment throughout the life course is important—and paid family leave policies taking effect in some states are a good start. But our work shows that encouraging women to work more will not be enough. We also need to ensure equal wages for similar work—as fought for by the U.S. women’s national soccer team—and to change workplace policies and cultural gender expectations around caretaking so as to reduce the penalties associated with family-related work lapses and parenthood.

Tania Cabello-Hutt is a PhD candidate in the Sociology department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Follow her on Twitter at @TaniaHutt and reach her at tcabello@unc.edu. Kate Weisshaar is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Follow her on Twitter at @kateweisshaar and reach her at weisshaar@unc.edu.

Comments