Many young adults today say that they are anxious or afraid of divorce. In many cases, they saw their own parents’ divorce up-close and want to avoid a similar fate. In other cases, they saw divorce play out from a distance, in their broader social networks, and eventually reached the same conclusion. Whatever the reason, many young adults say that although they generally approve of divorce, they are worried that they may one day go through a divorce themselves. Indeed, research shows that divorce haunts cohabiting young adults like a “specter,” and many choose to cohabit first as a way of “divorce-proofing” their eventual marriage.

Still, when it comes to how young adults think about divorce, few have paid attention to sexual minorities. Thanks to the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, however, sexual minorities can now think about marriage, and divorce, with respect their own lives. That is why, in our recent study (2021), we looked at written responses to open-ended survey questions about sexual minority young adults’ thoughts on divorce. All 257 of our respondents are unmarried individuals between the ages of 18-35 who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or queer.

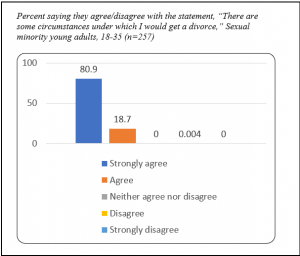

In stark contrast to the divorce anxiety so commonly reported by heterosexual young adults, the sexual minority young adults in our sample made clear that if they ever do get married, they would have no trouble divorcing. In fact, in response to the statement, “There are some circumstances under which I would consider getting a divorce,”approximately 81% said that they strongly agree, and another 19% said that they agree. To be clear, our respondents also indicated that they would try to avoid divorce, through active communication and seeking out marriage counseling if necessary. However, they consistently emphasized that they are not afraid of divorce and in many cases, do not see divorce as a negative outcome. As one 30-year-old bisexual woman wrote, “I would absolutely get a divorce, and I don’t see it as a last-resort, ‘Break glass in case of emergency’ type of thing. If it’s not working and two people are no longer in love or simply don’t want to be married anymore, then they should split.”

In general, our respondents tended to explain their willingness to divorce in one or more of the following ways. First, many said that they value their individual happiness and well-being more than they would value being married. Although most (60%) did express a desire to get married someday, many also explained that leading a happy, healthy life is simply a bigger priority for them. Second, some respondents said that they would be willing to divorce because they see being “stuck” or “trapped” in a bad marriage as a far worse outcome. Flipping the divorce anxiety script, these respondents are more worried about the possibility of an unsatisfying or troubled marriage than they are about divorce. Finally, a few said that they reject the idea that marriage is a lifelong commitment anyway. As one 32-year-old lesbian woman put it, “The possibility of divorce is part of marriage…It’s not failure, just time to change the structure and expectations of a relationship.”

Given that worries or concerns about divorce are so well documented among heterosexual young adults, our findings raise the question of how and why sexual identities might matter so much here. Our study cannot address this question directly, but we suspect that a significant factor is how sexual minorities are, as research suggests, socialized in both the dominant, heteronormative culture, which continues to celebrate marriage as a lifelong relationship, and in a distinctive queer culture, where individual autonomy is considered paramount, even in committed relationships. Perhaps participation in queer culture offers a kind of license to pursue divorce and thus helps to alleviate some of the divorce anxiety that heterosexual young adults so often report? Although not all of our respondents connected their willingness to divorce to their sexual identities, those who did tended to be the most willing.

It is important to note that some legal observers see warning signs that the Obergefell decisionmight soon be challenged and possibly overturned by the Supreme Court. But for now at least, national marriage equality is a settled matter, and as a result, we have a lot to learn about marriage and divorce in the lives of sexual minorities. Our study, like others, suggests that sexual identity does play a key role in shaping how people think about and approach marital relationships, and future research should continue this line of inquiry.

Aaron Hoy, Ph.D., is assistant professor of sociology at Minnesota State University, Mankato, where his teaching and research focus on families, sexualities, and qualitative research methods. He is the editor of The Social Science of Same-Sex Marriage: LGBT People and Their Relationships in the Era of Marriage Equality (Routledge, 2022). You can find him (mostly inactive) on Twitter @AaronHoy4

Jori Adrianna Nkwenti is a graduate student and Teaching Fellow in sociology at Minnesota State University, Mankato. She teaches Introduction to Sociology and is completing her thesis, “Accustomly Intermarried: Racial/National Intermarriages and their Negotiation of Family Celebrations.” Creator and author of Sprouting Sociologist and Soc.Sh*t, you can find her, iced coffee in hand year-round, scrolling through Twitter @tobor143.

Sachita Pokhrel is an undergraduate student at Minnesota State University, Mankato, currently pursuing a BS in Sociology and Psychology

Comments