Reposted with permission from the Gender & Society Blog

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened inequalities in unpaid care work, with increased childcare and housework burdens disproportionately borne by women. Across Europe and North America, women have been pushed out of the labor market, while mothers are increasingly suffering from stress and burnout.

Social policy might be able to reverse these trends – and the Carework Network has been urging the Biden-Harris administration to take decisive action now and reinvest in care infrastructure to “build back better”. Similar campaigns have been launched internationally, including in Canada and the UK.

But what can data tell us about the potential for welfare programs to address the gender gap in unpaid care work?

In our recent article in Gender & Society, we quantify the connections between social policy spending and inequality amongst unpaid care workers across 29 European countries.

We find that social policies do matter in addressing women’s “double burden” (at home and in paid work). Spending on social policies targeted to families – i.e., child allowances and credits, childcare supports, parental leave supports, and single-parent payments – is associated with a smaller gender gap in time spent on housework. And while this dynamic is visible across the income spectrum, it is strongest in lower income households.

The Gendered and Classed Dimensions of Unpaid Care

Data from the 2007/2008 and 2016/2017 waves of the European Quality of Life Survey highlights the scope of the care crisis even before the onset of the pandemic.

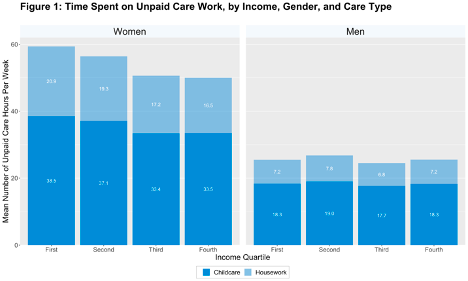

Figure 1 presents the mean weekly number of hours spent on unpaid care, broken down by care type (i.e. childcare as compared to housework), gender, and income quartile, for people living with at least one child under the age of 18 years. Several patterns emerge.

First, across all income groups, childcare makes up the majority of time dedicated to unpaid care work. This means both men and women spend proportionately more time caring for children than cooking and cleaning.

Second, women devote around twice as much time to unpaid caring as men. This pattern is consistent across the income spectrum, though the gender gap is especially large in lower income households.

Third, women with higher household income spend less time on unpaid care work than their poorer counterparts – likely because wealthier women outsource work to paid care providers. Men, by contrast, dedicate similar (lower) amounts of time to unpaid care work regardless of income level.

Fourth, childcare makes up a larger proportion of unpaid care work for wealthier women than for poorer ones. This reinforces prior research on “intensive mothering”: time spent educating children has become an important means of class reproduction within higher-income families, while “menial” tasks such as cooking and cleaning are more readily outsourced.

Spending on Family Policy is Associated with Reduced Inequalities in Housework

Using national data from the Organisation for Economic Development and Co-operation’s SOCX database, we then examine the state’s potential role in reducing inequalities in unpaid care work.

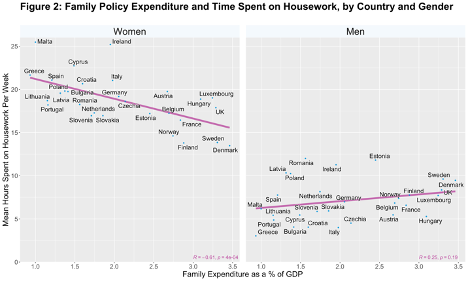

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between how much a country spends on helping families (as a percentage of GDP) and the mean number of total hours spent by women and men, per country, on housework.

The two panels highlight that the gender gap in unpaid housework is a common feature across each of the 29 countries we examine. Regardless of the country or level of spending, women continually perform more unpaid housework then men.

Yet the data also show that the more a country spends to help its families thrive, the fewer hours women spend on housework. Women in countries where money spent on families accounts for a higher proportion of GDP spend less time, on average, doing unpaid housework tasks.

Using Family Policy to Build Back Better

Our analyses show that while women – and especially poorer women – spend more time on unpaid care work than men, carefully designed social policy spending may help to shrink the size of that gender gap. For governments, then, (re)investing in social programs that target families offers a promising route forward to counteract the large increases in unpaid care work that have occurred during the pandemic. These programs should be a crucial component of post-pandemic efforts to create a more equitable and caring society.

Naomi Lightman is Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Calgary. Her current research focuses on the of impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the employment conditions and health and well-being of paid caregivers in long-term care settings. Her related research publications examine the intersections of gender, inequality, care work (paid and unpaid), and social policy. You can follow her on Twitter @naomilightman.

Anthony Kevins is Lecturer in Politics and International Studies at Loughborough University. His research centers around inequality, public opinion, and various social policy programs, often with a focus on labor market vulnerability. You can read more about his research on his website, which also includes non-paywalled, open-access copies of his published studies – and you can follow him on Twitter @avkevins.

Comments