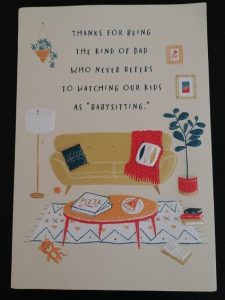

A few days before Father’s Day in June 2021, I found myself in the greeting card aisle leafing through the rows of cards capitalizing on the celebration of men’s parenting. One in particular caught my attention. On the front was a pale-yellow image of a modern living room scene with an open pizza box on the coffee table and books and a stuffed teddy bear lying on the floor. The caption read: “Thanks for being the kind of dad who never refers to watching our kids as ‘babysitting’,” and upon opening, “You’re a good one. Happy Father’s Day.” Did the card represent progress by implying that “good” dads take for granted that caring for their own children is parenting, not babysitting? Or did it reflect the ever-low bar for fathering and the idea that men deserve appreciation when they do the bare minimum of carework?

My card conundrum took on special meaning given that 2021 marked the 111th annual Father’s Day, a holiday that can be traced back to Sonora Smart Dodd’s efforts to honor her father, a widower who single-handedly raised six children. It also marked 15 months – well over a full year – that many families had been working and learning remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In a country where the vast majority of fathers take less than 10 days of paternity leave from paid work after the birth or adoption of a child, the pandemic was the first time many men spent most of their awake hours in the vicinity of their children. Historically, moms have done the bulk of childcare, homework help, and housework necessary to keep kids clean, educated, fed, and clothed. Has the pandemic changed that?

Much like with that Father’s Day card, the answer depends on how you look at it. The pandemic compelled many families to reevaluate the starkly lopsided gendered division of household and parenting labor. Early in the pandemic, both mothers and fathers reported that they were sharing housework and childcare more equitably. Lost jobs, income, and work hours meant more economic stress for families, while closed workplaces, schools, and daycares forced more paid and unpaid labor into the home. Fathers picked up some of the slack. But mothers picked up even more. And they didn’t always agree about who was doing how much. The pandemic certainly hasn’t closed the persistent gap between our cultural views of fatherhood that have long included expectations for men to be involved dads who provide care and time, not just money, and men’s actual parenting behaviors. The lag separating the culture and conduct of fatherhood that historian Ralph LaRossa described over three decades ago endures.

Yet, now over a year and a half into the pandemic, evidence suggests that we have reasons to celebrate. Fathers have spent more time with and felt closer to their children. They’ve gotten to know their children more and discovered new shared interests. Some laud more paternal playtime as a “gift of the pandemic.” Many became more involved in their children’s education and stepped up in other ways around the house that became workplace, schoolroom, and daycare facility all wrapped into one.

But the pandemic didn’t upend deeply entrenched gender inequities in carework – the devalued, often invisible, and less playful aspects of parenting that include cleaning, cooking, and cognitive burdens such as grocery list-making and tracking homework due dates. A huge gap remains between our cultural ideas of “involved” dads and the reality that the labor burdens of parenthood still fall much more heavily on women. A major reason for that is that American fathers tend to fall back on their breadwinner responsibilities in times of economic crisis. It didn’t help that women lost more paid jobs during the height of COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders, nor that governmental responses to the crisis were slow and uneven across different states and communities.

In our work-first culture, we still hold men accountable for families’ financial well-being, despite how women have long been primary or co-breadwinners in most families. This was especially evident in my research on fatherhood programs for low-income fathers of color who worked hard to cast off the “deadbeat dad” label so often applied to marginalized men who struggle to live up the masculine breadwinner norm. Directly challenging racist stereotypes that fathers of color are more likely to be absent and less involved with children, Black fathers are actually more likely than white dads to feed, eat meals with, bathe, diaper, dress, play with, and read to their children. Provider expectations, especially for men who face limited job prospects, can undermine a personal sense of parental value and worth.

We saw this too during the pandemic. During a social and economic crisis when mothers were more likely to lose their jobs and governments and employers did little overall to help them manage the unprecedented COVID care burdens, it’s no wonder that traditionally gendered roles of parental responsibility shaped how much dads stepped up – and then stepped out. We still give dads more credit for paid work and breadwinning than for unpaid care and breadmaking.

I’m still not sure how I feel about that Father’s Day card and whether it reflects how far we’ve come in creating equitable conditions of parenting – or rather just how far we have left to go. One thing is certain. Regardless of gender, parents in the United States lack adequate public support for the labors of parenting as the pandemic continues to unfold. Maybe next year there will be a Father’s Day card that honors the work, both paid and unpaid, that it really takes to raise children. Perhaps I’ll find one that harkens back to the original vision of Sonora Smart Dodd who wanted to celebrate her father stepping up to the role of primary parent – not babysitter – when a crisis demanded it.

Jennifer Randles is Professor and Chair of Sociology, California State University, Fresno

Comments