The puzzle. The COVID-19 crisis has resulted in an unprecedented shift to remote work, with 55 percent of currently employed parents working from home in April/May 2020. At least some of the pandemic-related shift to telecommuting is likely to persist for some time, with companies like Facebook moving to permanent remote work for many workers. What does this mean for the perennial issue of work-family conflict, and additionally, what are the implications of expanded telecommuting arrangements for gender equality at work and in the households of parents with children?

On the one hand, telecommuting can ease work-family conflict by giving workers greater control over their schedules. Mothers of young children particularly value telecommuting, and flexible work has been linked to higher rates of maternal employment. Although mothers still do a great deal more housework and childcare than fathers, the amount of childcare done by fathers has increased almost threefold since the 1970s, and in 2019 fathers, on average, spent 55 minutes per day caring for children. Fathers also report that they would like to be spending more time with their children, so working from home could be a way for fathers to increase their share of housework and childcare. For many working couples, then, telecommuting may be an attractive and egalitarian strategy for managing the competing demands of work and family.

On the other hand, telecommuting can worsen rather than ameliorate gender inequalities in the home and in the labor market. Workplaces provide a barrier, both physical and psychological, between parents and demands to do additional childcare and housework. Social pressures to spend intensive time on child-rearing and on housework are much stronger for mothers than fathers, and once the separation from home life provided by workplaces is removed, this may lead mothers to increase the amount of household labor they do by more than fathers.

Early indications of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender inequality have been contradictory, with different surveys suggesting that gender gaps in household labor have either narrowed or widened, depending on whether the researchers focused on housework and childcare alone or included home schooling.

The data. We examine the links between telecommuting and gender inequality with data collected before and during the COVID-19 crisis: the 2003-2018 American Time Use Survey (ATUS, N = 19,179) and the April and May 2020 COVID Impact Survey (N= 784). This allows us to report on gender differences in parents’ household labor and work contexts for parents working in the workplace, at home, and splitting their time between the two before the pandemic, as well as to assess the impact of telecommuting that was a direct response to the pandemic and has been taking place in the context of schools and child-care centers being shut down. We also use a subsample of regular telecommuters in ATUS (N = 339) to compare the behavior of mothers and fathers on days in the workplace and days working from home. The parents in this sample tend to be more similar in their work-related characteristics relative to a broader group that includes those who never work from home.

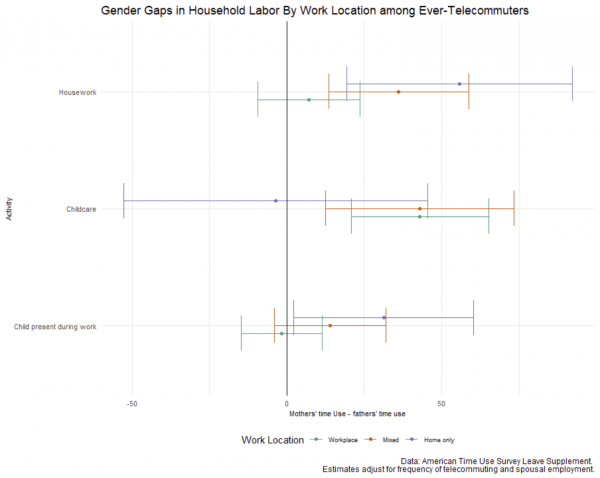

The results for pre-COVID-19 childcare: Telecommuting dads catch up with moms. In general, telecommuting parents put more time into household labor than do parents who work at a separate location. But prior to COVID-19, we found an interesting gender difference in what types of household labor individuals did more of when working from home, and this produced two diverging patterns in the division of total household labor. Under ordinary circumstances, telecommuting fathers increase the amount of childcare they do more than do telecommuting mothers. Looking at a subsample of mothers and fathers who all reported telecommuting some days for their job, we find that dads spent 67 more minutes caring for children on the days they worked exclusively from home than on the days they worked exclusively from the workplace. This increase in childcare time was 47 minutes larger than the average increase in childcare we find on days when mothers worked from home, and it appears to effectively close the gender gap in childcare hours (see Figure 1). By contrast, gender gaps in childcare were substantial for workers who mix their time at home and the office or who work only from the office. These results suggest that telecommuting can bring fathers closer to parity with mothers when it comes to childcare.

The results for pre-COVID-19 housework: Telecommuting moms, but not dads, do more. But for housework the opposite is true. Comparing mothers and fathers in the same sample as above, we find that on the days mothers worked from home, they increased their housework by 49 minutes. Fathers did no more housework on days when they worked from home than on days when they were absent from home while working. So when it comes to the division of housework, unlike the division of childcare, telecommuting may be associated with increased gender inequality.

The results for pre-COVID-19 work-family conflict: Children spend more than twice as much time in the presence of telecommuting moms when the moms are working than they do with dads. The issue is further complicated by the fact that people who work at home are sometimes in the presence of children even when they are not doing childcare but are working – or trying to work. This creates spillovers from the parental role into the employee role. When people are forced to juggle their attention between children and work, they experience a form of work-family conflict that is absent in work settings separate from the home – one that leaves parents unable to give either work or home life their full attention. This conflict is far more intense for telecommuting women than for their male counterparts.

In general, parents working from home report that their children are with them while they work far more than do parents in the workplace. But while telecommuting fathers reported children as present during work for 21 minutes per day, on average, on days they worked from home, mothers reported children present during work for 54 minutes per day, leaving a gender gap of 27 minutes (Figure 1). That this kind of work-family conflict disproportionately affects mothers may have downstream consequences for labor market gender inequalities, as the quality or productivity of working time may be lower for telecommuting mothers than fathers.

Why do moms do more? Our research doesn’t tell us why, exactly, telecommuting mothers do so much more housework. But we know that women often hold much stricter standards than men about the amount of laundering and daily cleaning that has to be done. While these may be “choices” made by the mother or the couple, they are often choices constrained by the tremendous pressures that women – especially married women – feel to “keep up appearances” in the home. Women also tend to feel much more pressure than men to live up to the ideals of intensive parenting. Whatever the reasons that telecommuting mothers spent more time on housework and were more likely to be interrupted by children while trying to work, the consequences seemed to counteract many of the advantages of telecommuting. Comparing the wellbeing of mothers working from home and a separate workplace before COVID-19, we find little evidence that telecommuting resolved work-family conflict: Telecommuting mothers were no happier, and no less stressed or tired, than mothers working from a workplace.

Implications? Assessing the implications of telecommuting for gender equality is especially complicated in the United States, where government support for working families is far less generous than that provided by other rich countries. Most localities do not provide free or subsidized childcare, and its unsubsidized cost is prohibitive for many families. In this context, telecommuting is a choice many parents make to solve a childcare problem. It may be the best choice in the circumstance, but it should be no surprise that making such a choice involves work-related tradeoffs, and that, given parenting norms, these tradeoffs are more severe for women. As an example, using a simple approach that assigns median earnings to average changes in work hours associated with housework, we estimate that the potential annual earnings mothers lose by devoting extra time to housework instead of wage-work is $660 for mothers who telecommute one day a week, and $2638 for mothers who telecommute four days a week.

These patterns suggest that even under circumstances where telecommuting is not a substitute for childcare or full-time school, it poses some threats to the long-term progress of gender equality, at least when engaged in by women. Given the intense socialization of women into not being able to ignore perceived demands of children and dust bunnies alike — and the outright shaming they often experience when they do ignore them — there may be some benefits to working outside the home for women. By contrast, given their socialization to be able to ignore the demands of children, there may be some benefits to working inside the home for men.

The results on working at home during the pandemic. The conditions of telecommuting imposed by COVID-19 are especially likely to increase gender inequalities in household labor and the labor market. The closure of schools and childcare facilities greatly increases childcare burdens on parents, with telecommuters now expected to educate their children alongside doing their day jobs, a job that has so far fallen most heavily on women. Overall, parents in the workplace report less depression than telecommuting parents. But the extra stress for telecommuting women is striking. Mothers telecommuting during April – May 2020 reported feeling anxious, depressed, and lonely at significantly higher rates than telecommuting fathers, who unlike actually mothers experienced less anxiety when working from home. For parents in the workplace, we found no statistically significant gender differences in rates of stress and depression (see Figure 2).

Implications, taking COVID-19 into account. Our findings on telecommuting both before and during the pandemic point to families’ –and society’s– urgent need for more government support for parents. Telecommuting has real benefits. It gives parents greater flexibility to structure their work, saves time commuting, and allows parents to spend more time with their children. And given COVID-19, telecommuting is surely the best option for parents at the moment. But when parents have to combine working from home with looking after children, it is easy for telecommuting to exacerbate gender inequalities in both formal and informal work. Even with fathers doing more, telecommuting with children detracts from mothers’ work environments and is associated with more stress. Subsidizing childcare, and, where possible, reopening schools in the fall would greatly reduce this tension. But until science suggests it is safe to do so, employers must be urged to rethink traditional measures of productivity and recognize the need for men as well as women to make the work adjustments they need to as they strive to cope with these unprecedented demands on their time and energy.

—

Notes

Childcare Measures

In our paper, we construct two different measures of parents looking after children. First, we create a measure of childcare that combines basic care activities of younger children (e.g., feeding, bathing) with activities relating to education (e.g., helping with a child’s homework or attending a PTA meeting) and health (e.g., sitting with a sick child) and associated travel of all children under 18. This measure captures time spent explicitly caring for children. Second, we construct a broader measure of all time parents spend with household children when they are actually doing tasks other than childcare. This broader measure captures time during which parents may be splitting their attention between looking after children and another activity. We use this measure to analyze the presence of children while parents are working. In our full paper, we also look at gendered differences in time with children by telecommuting, and we find results that are similar to our reported estimates of childcare (see paper Table 2).

Couple-level Dynamics and Same-Sex Partners

The American Time Use Survey collects information on all members of a household, including couples, but only records time use data, including childcare and housework, for one person per household. This means that we can examine how telecommuting parents’ behaviors differ based on their partners’ employment, and we find that telecommuting fathers particularly increase the amount of childcare they do when their partners work full time (more than 35 hours per week). But we do not have information on partners’ telecommuting, and thus cannot assess how parents react to their partner’s telecommuting. The number of telecommuters in our descriptive sample (788 parents telecommuting for full days) also prevents us from examining same-sex couples. Without such narrowly prescribed gender roles to fall back on, same-sex couples divide childcare and housework tasks more fairly than opposite-sex couples, and so we would expect their reaction to telecommuting to also differ. This could be a fruitful avenue for future research.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE CONTACT:

Thomas Lyttelton is PhD candidate in Sociology at Yale. Contact him at thomas.lyttelton@yale.edu . Emma Zang is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Yale; contact her at emma.zang@yale.edu.

Kelly Musick is Professor and Chair of Cornell Policy Analysis and Management and can be reached at musick@cornell.edu.

LINKS AND ABOUT:

Brief report: https://contemporaryfamilies.org/covid-19-telecommuting-work-family-conflict-and-gender-equality/

Press release: https://contemporaryfamilies.org/covid-19-telecommuting-work-family-conflict-and-gender-equality-advisory/

Comments