While gender inequalities between women and men who do not have children are narrowing if not disappearing, the economic gap between mothers and fathers remains large and shows little sign of closing. Quite a bit of attention has been paid in the popular and scholarly press to the “motherhood penalty,” or earnings losses associated with becoming a mother. In the US, women’s earnings drop by 30% when they become mothers.

Until recently, relatively little attention has been paid to how these motherhood penalties translate into inequalities between partners, or within couples. Most studies on the motherhood penalty compare earnings between mothers and fathers as separate groups, and less is known about the impact of the motherhood penalty at the couple level. Moving to a focus on couples is important because it highlights how couples strategize about time and money following parenthood and how gender inequalities reproduce at the couple level.

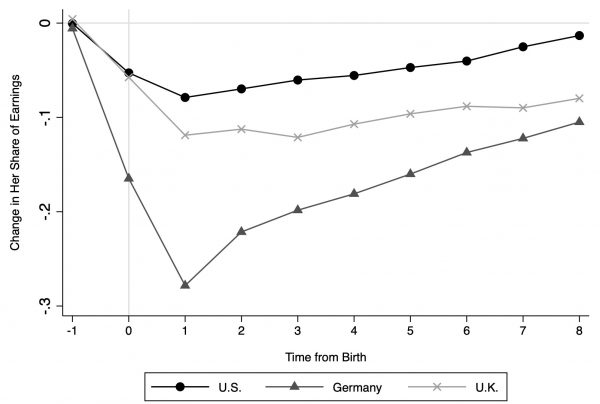

Our study uses data on heterosexual couples from the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom to study how parenthood shapes gender inequalities at the couple level. We use longitudinal data, which means that we can follow the same couples over many years. We select a group of couples who are observed making the transition to parenthood during the survey, so that we can observe couples’ earnings when they do not have a child and follow them as they become parents and up to eight years after the transition to parenthood. To measure gender inequality at the couple level we use women’s share of couple earnings (e.g., 0% indicates that the male partner is the sole earner, 50% indicates equality in earnings, and 100% indicates that the female is the sole earner). Using this measure, our study asks: how do women’s share of couple earnings change after couples transition to parenthood?

Our results show that it changes a lot.

We find that parenthood results in large and enduring increases in gender inequalities within couples in all three countries. In the US, women’s share of couple earnings drops 8 percentage points, from about 40% to 32%; this decline is larger in the United Kingdom (12 percentage points) and largest in Germany (28 percentage points). Importantly, these declines in women’s share of couple earnings are not short-lived, on the contrary, they appear to persist over time. Following couples to the end of our study period, eight years following parenthood, we continue to see evidence of post-birth earnings losses in her relative earnings. Overall, these relative losses amount to large and substantial long-term declines in women’s economic power within couples.

Because we analyze couples across countries, our study is also able to assess how different work-family policies and cultural contexts shape how gender inequalities at the couple-level evolve with parenthood.

The relatively larger decline in women’s share of couple earnings in Germany compared to the US and the UK is in line with expectations stemming from Germany’s historical (albeit evolving) policy emphasis on and public acceptance of men’s breadwinner role, including long maternity leaves and a lack of childcare options prior to kindergarten. The relatively smaller declines in women’s share of couples’ earnings with parenthood in the US and the UK reflect a policy environment where care is seen as a private family responsibility and the dual-earner family model is more widespread.

Changes in women’s share of couple earnings can result from various processes. For example, it is possible that both men and women reduce work commitments with a newborn, but that women’s reductions are greater than men’s. It is also possible that women remain employed but change jobs that pay less and result in a decline in her share of earnings. Our evidence suggests neither of these patterns.

Instead, our results show that in all three countries women’s share of couple earnings declines largely because women reduce employment and work hours, while men change neither. Our analyses show no evidence that men’s employment changes over the transition to parenthood, whereas women’s employment drops by almost 20 percentage points in the US and nearly 40 percentage points in Germany. Changes in women’s work hours are similarly large and have a significant impact on women’s share of couple earnings, while changes in women’s wages are smaller and do not contribute as much to changes in her earnings share.

When we broke down the analysis by whether or not the mother had a college degree, we found additional and important differences across the three countries. In Germany and the UK, the declines in women’s share of couple earnings are smaller among couples with a college-educated mother than those with a less-educated mother. This pattern is consistent with the expectation that women’s employment trajectories respond to their earnings potential and that women who have the most to lose from dropping out of the labor force are the most likely to remain employed after they become mothers.

In the US, however, we find the opposite, that declines in women’s share of couple earnings are relatively larger among couples with a college-educated versus less-educated mother. The difference between the two groups is not very large, but the pattern is distinct in substantive and meaningful ways, especially from what we see in Germany.

The fact that increases in gender inequality within couples in the US are smaller among the less-educated is consistent with the idea that a weak welfare and work-family policy environment puts couples under distinctive economic pressures. At the low end of the education distribution, US couples are less buffered by resources to manage work and family demands, in terms of their own earnings to purchase childcare and other services, but also in their ability to rely solely on one partner’s earnings to make ends meet. They face strong financial pressure to remain attached to the labor market following birth. At the high end, long and inflexible hours in professional jobs make it difficult for college-educated to maintain dual-earner families, and reliance on one income may prove a more viable option for some.

On the whole our analyses show that: 1) parenthood results in substantial and long-term increases in gender inequality within couples, 2) these increases result from changes in women’s work patterns following parenthood, not men’s, and 3) policy and cultural contexts shape how couples strategize time and money after parenthood. Together, these findings highlight how the transition to parenthood can deepen inequalities within couples as they navigate this new stage of their family life. Importantly, the gendered earnings disparities that emerge may negatively impact other domains of family life, including power dynamics between partners, household decision-making, and mothers’ economic independence. Although income gaps between women and men without children may be closing, our study illuminates how the transition to parenthood produces persistent income gaps within couples.

Pilar Gonalons-Pons is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. Kelly Musick is a Professor and Department Chair of Policy Analysis and Management at Cornell University. Megan Doherty Bea is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Consumer Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Comments