Why is it taking so long for women to overcome sexism and enjoy equal rights to men at work and at home? We saw swift gains for women as the second wave of feminism swept through America in the 20th Century. But not so much in the new Millennium. In fact there seems to be a stall in progress. The gender wage gap isn’t shrinking, women are no longer increasing their representation in traditionally male fields, nor have women’s labor force participation continued to increase. One of the answers often given is that people, even young people, are tired of trying so hard. The world just isn’t organized for everyone in a family to be engaged in full-time paid labor, so something’s got to give. And maybe, these skeptics say, it should just be women’s rights. Some have even suggested that Millennials are reverting to traditional gender attitudes where they prefer women to be the primary caregivers in the family. But we don’t think so. After all, Millennials are also the generation behind the Women’s March and the resurgence in feminist activism.

So we set out to find out what was really going on. We particularly wanted to know about generational changes in attitudes. Are young people still the beacon of new and progressive ideas, or do Millennials, having watched their parents struggle with two-paycheck families, now yearn for the simplicity of a Fathers Knows Best world where men go to work and mothers bake after-school cookies? To that end, we analyzed responses from over 27,000 people surveyed by the General Social Survey from 1977 through 2016 to examine how gender attitudes have changed over the past 40 years, and whether each generation is more liberal, or if younger people yearn for the less harried past.

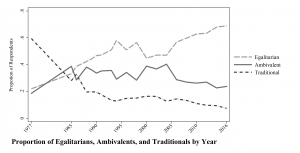

What we found is that truly traditional people, those who do not believe in equal rights for women at home or at work, have nearly disappeared. In 1977, less than a quarter of the population felt women and men should be equal. Back then, the majority of Americans supported very traditional roles for women and men. They felt that women were unsuited for politics and that they should focus on raising children and not participate in the labor force. By 2016 these traditional views were virtually non-existent, with only 7% of the population holding such beliefs. The proportion of those with egalitarian beliefs has tripled to 69% of the population. In forty years we have gone from just a quarter to more than two-thirds of Americans believing in gender equality at both work and home. Given that men have ruled the public sphere throughout human history, the pace of change has actually been quite startling. While there have been ebbs and flows, particularly at the turn of this century, egalitarian beliefs have increased over the years, and recent trends indicate that they will only continue to become more common.

The second big finding, not so surprising, is that those traditional people didn’t all become enthusiastic feminists. Those who held traditional views were replaced by individuals who support gender equality at work but not at home. We call these people ambivalent, because they embrace some but not all aspects of equality. The majority of these ambivalent people support women’s equal participation in the public sphere, but hold on to traditional beliefs about women’s responsibility for childrearing and family labor. A quarter of the population still hold such ambivalent views, but this shouldn’t overshadow the biggest finding, that more than two-thirds of Americans now fully endorse egalitarian beliefs.

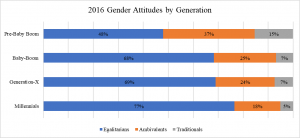

What did we learn about generational change? Millennials are the generation most likely to hold egalitarian views. More than three-quarters of Millennials felt women and men should be equal in both the public sphere of work and the private sphere of the family. Indeed every generation is more liberal than the one before. The biggest jump in attitudes was between Baby-boomers and those that came before them. There was just a little change between Baby-boomers and Generation-X, but then Millennials are considerably more egalitarian then GenXers. So much for the myth that younger generations are tired of the struggle for equality!

So this is all good news. And we feel very lucky that our study has received a great deal of attention in the press in the last week. The New York Times kicked off the coverage of our new research with a very accurate, quite wonderful article by Claire Cain Miller. While that article was spot on, many others that have followed are somewhat misleading, at least the headlines. Now, we know journalists don’t write the headlines. But people do read them, and many people may only read them! And many of the titles about this research suggest that Americans value equality only at work, and not at home. There seems to be a strong cultural belief guiding press coverage, or at least headline writing, that suggests nothing gets better and denies that feminism has changed the world. Headlines in such places as the Economist, Working Mother and CNBC implied that our research highlighted the sad story of women’s continued oppression.

That’s not what we found at all. In fact, our data suggest that most Americans support equality at both work and home, while a minority of Americans, likely to be older, male, white, and less educated, are ambivalent about equality, supporting women’s rights at work, but wanting them to continue to shoulder the responsibilities at home. Every generation has become more liberal, and we have made amazing strides in just forty years.

We are honored that our research is being covered, and is now available for conversation among people who don’t take our classes! We are concerned, however, that this story about the failure of feminism has become so strong a narrative, that even data can’t move it. Let us be clear: our research suggests that after the second wave of feminism, attitudes have radically changed in support of gender equality. Yes, there are old white uneducated men out there who are still ambivalent, but most of us are not. Most Americans support gender equality, and the Millennials are the most egalitarian generation yet.

Of course, despite progress on attitudes toward gender equality, we continue to see much sexism all around us. The #meetoo movement has revealed how deeply male privilege to women’s bodies is embedded in our culture, in men’s attitudes and behaviors. The 2016 presidential election proved that open hostility to women’s rights was no impediment to election to the highest office in the land. And the pace of change for women’s equality at work, from wage-gaps to sex segregation of the labor force, has indeed stalled.

Gender discrimination exists but what our research shows is that norms that justify it are changing. Now it’s time to make sure the laws, policies and regulations that shape our everyday experiences change too. As norms change, as more women are elected to political office, and as fathers take a more active part in parenting, we need our political institutions, and our workplaces to change. Mothers need to breastfeed on the Senate floor, fathers need paternity leave to do their share of infant care. Imagine the progress we’d see if there were family policies for egalitarian parents who want to live their values without having to contend with societal impediments that stand in the way of the gender equality. Most Americans want public policy that supports employed parents and women’s rights.

For now, let’s be pleased at how far we have come changing American attitudes. Let’s honor the incredible successes of the 2nd wave of feminism. We can do that even as we acknowledge how much more work needs to be done to continue to push our society toward a future where men and women, mothers and fathers, actually have equal opportunities at work and at home.

Comments