A briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families Online Symposium on Gender and Millennials, originally released March 31, 2017.

Overview. In their briefing paper, “Trending toward Traditionalism?” Pepin and Cotter report on a remarkable reversal of the attitudes held by U.S. high school seniors about gender in families: While subsequent cohorts exhibited increasingly egalitarian attitudes until the mid-1990s, they moved back towards more conservative opinions afterwards. Fate-Dixon found similar trends among 18-to-25 year olds.

Despite these findings, I think that the big structural trends are still pushing towards more gender equality in the U.S. as well as elsewhere in the West. Generations coming of age in the late 20th or early 21stcentury still grew up in a world that was largely dominated by men, certainly in politics and the economy. However, this is changing among the generations being born in the early 21st century. While couples these days are most likely to have the same level of education, there is a new pattern among the roughly 40 percent who don’t match. According to a U.S. 2012 study, a woman’s educational achievement is now slightly more likely exceed her husband’s than vice versa, a trend that seems to be accelerating in many countries. This means that new generations of women are sometimes better educated than their husbands. If that is the case, they are also more often the main breadwinners of their families than in comparable couples where the wives are less or equally educated. While attitudes about gender may stall or even exhibit some conservative backlash, structural forces continue to push towards more gender equality.

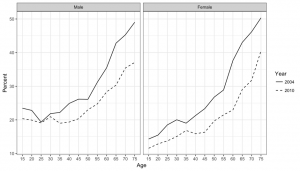

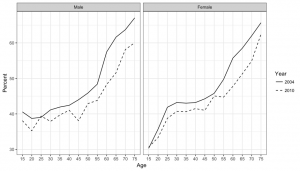

U.S. versus Europe. Full-fledged comparison of the American findings by Pepin and Cotter with European attitudes is not possible because the equivalent data for Europe are lacking. Yet, as far as the evidence goes, we see no signs that attitudes about gender are turning less rather than more conservative among Europeans, whatever their age. Figures 1 and 2 below plot the proportion of respondents in the European Social Survey agreeing with each of the following two statements: “Men should have more right to a job than women when jobs are scarce”; and “Women should be prepared to cut down on paid work for sake of family.” We give separate graphs for male and female respondents, and we plot the proportions of people agreeing at different ages, ranging from 15 to 75 year olds, and in two different years (2004 and 2010).

The most striking feature of both figures is that the lines go up dramatically from left to right, implying that younger men as well as women tend to agree much less with conservative statements about gender. Second, in the more recent round of the European Social Survey, in 2010, the responses tended to be less conservative and more gender egalitarian than six years earlier, in 2004 – as indicated by the fact that the dashed line is almost always below the solid line; otherwise, the lines just touch, indicating stability over time. While 15 to 20 year-old men tend to agree more often with the conservative statement than 20 to 25 year-old men, the most recent cohort of men below age 20 has taken a more, not less, gender egalitarian stance.

Figure 1. Percentage of Europeans agreeing with the statement “Men should have more right to a job than women when jobs are scarce”; responses in the European Social Survey in 2004 (solid lines) and 2010 (dashed lines), men (left) and women (right) aged 15 to 75

Figure 2. Percentage of Europeans agreeing with the statement “Women should be prepared to cut down on paid work for sake of family”; responses in the European Social Survey in 2004 (solid lines) and 2010 (dashed lines), men (left) and women (right) aged 15 to 75

As far as the evidence goes, the European trends in attitudes do not seem to move in the same direction as was found among high school seniors and 18-to-25-year-olds in the U.S. Despite the turn towards more conservative gender attitudes found by Pepin and Cotter and Fate-Dixon in the latter group, there are good reasons to expect that actual practices and behavior will continue to move towards more gender equality in the U.S. as well as in Europe.

Europe doesn’t have the reversal—but what does it mean? In earlier generations, if there was a difference in educational attainment level between mom and dad, it was typically dad who had the higher degree. This was the case in the United States until about 2012. In recent generations of high school graduates who were raised in double-earner families, the father usually had the higher degree in education, giving him the higher income potential, and in fact earning most of the family income. While the mother also typically went out to work for pay and contributed to the family income, her role as economic provider was typically secondary, supportive of his status as the main earner.

Recent studies showed that this is changing, not only in the West but globally. As populations across the globe become more educated, women tend to accumulate more education than men, leading to a reversal of the gender gap in education to the advantage of women.[1] This holds also on the couple level: In countries with a reversed gender gap in education, it is more common that the wife has more education than the husband, rather than the other way around.

When women are better educated than men, they may also have higher earnings potential. Yet, the gender gap in earnings still remains to men’s advantage. Among other things, this is related to the fact that women choose less lucrative study subjects and occupations and that women typically face a motherhood penalty on earnings while men rather receive a fatherhood bonus. As explained by Pepin and Cotter, the cultural orientation of gender essentialism may be the explanation, i.e. the idea that men and women hold innately and fundamentally different in interests and skills.

Yet a recent study indicates that the gender gap reversal in education has the potential to undermine the motherhood penalty. When a wife has a higher degree than her husband, not only are the chances clearly higher that she can become the main earner of the family but it also offsets the motherhood penalty, especially in countries that make it easier for women to combine careers and parenthood.[2] In Europe, when both partners have a college degree, the share of couples where she earns more than he does is around one in three among childless couples, while it is only around one in five among couples with school-aged children. However, when a wife has a college degree but her husband doesn’t, the share of coupled parents where the wife earns more than her husband is just as high as among childless college-educated couples, i.e. around one in three. This suggests that earnings potential and work experience may start to outweigh any cultural preferences of women to cut back at work after having children.

Furthermore, a female advantage in education or earnings (or both) is no longer associated with lower marital stability. This was the case in the past, but this is changing. One study found that the wife’s employment was still associated with a higher risk of divorce in the U.S., but not in European countries nor in Australia. In fact, in Finland, Norway, and Sweden, wives’ employment even predicted a lower divorce risk compared to couples where the wife stayed home.[3] More detailed study of time trends in the U.S. recently showed that while couples where she was more educated than he or where she earned more than he were more at risk of divorce in the past, but not anymore today.[4]

Why have attitudes among American youths shown a more conservative trend in recent years? An obvious explanation could be a romantic kind of backlash. These are the first kids who grew up with two working parents, if not with a single mother, with all the stressful situations this entails, particularly in a society whose institutions and companies are not quite adjusted to the new gender roles yet. Youngsters may romanticize the male breadwinner, female homemaker model, which they may still see in the movies and on television. Their mothers were typically doing extra housework shifts after their work commitments, which may not look like an attractive future for younger generations, especially when despite two working parents the income of the middle classes stopped growing[5] and many families faced difficulties keeping up with the increasing demands of consumer culture.

Even so, it remains to be seen whether the stall or even backlash observed in attitudes in the U.S. will continue. As I noted above, the recent shift in relevant attitudes observed in Europe are still moving in the direction of support for more gender equality. If I had to put my money on it, as the current American high school seniors and under-25 youths grow older, they will experience that their own families will be better off if they can pool and share resources rather than having the wife specializing in unpaid household work and the other in paid market work. As a result, I would expect that the attitudes will adjust to the reality, which is moving in the direction of more gender equality.

Jan Van Bavel is a Professor of Sociology at University of Leuven.

Comments