Part 1 of the Council on Contemporary Families’ Symposium on Welfare Reform at 20

The welfare reform bill that emerged in 1996, after a back-and-forth struggle between President Bill Clinton and the Congress (both houses of which were controlled by Republicans), imposed a two-year continuous term limit, and a five-year lifetime limit, on poor cash welfare recipients. It ended Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), an entitlement program, and replaced it with Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, a state block-grant program. The policymakers who engineered this change took advantage of a growing popular expectation that mothers should be in the labor force. There was widespread resentment against those (perceived to be mostly Black) who used welfare payments to shirk the obligation to work, choosing dependence on the state rather than getting married or refraining from childbearing.This policy reform, motivated and supported at least in part by racist ideas and stereotypes, set out to fundamentally alter the relationship between work, parenthood, and marital status for U.S. women. Instead, despite some increase in employment rates, it mostly increased the hardship – and reduced the support – for poor families and their children, who are disproportionately people of color. Reflecting on this anniversary, it now appears this was a tragic misdirection, and we lost an important opportunity to change work family policy for the benefit of all women and poor families.

Politics and the rise of welfare reform

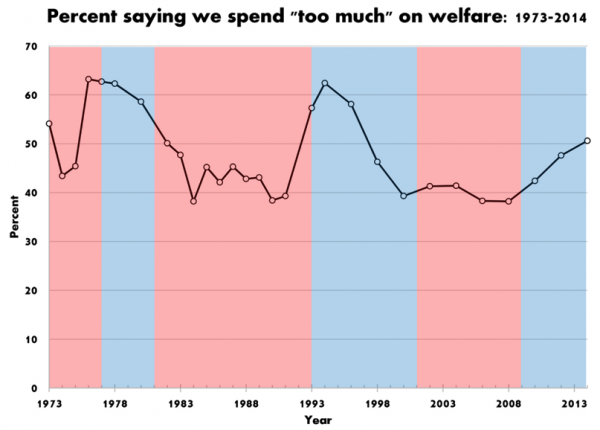

In 1994, the percentage of Americans telling the General Social Survey the government was spending “too much” on welfare peaked at 62 percent, having jumped almost 20 points around the 1992 election that brought Bill Clinton to power. We can now see this as a cyclical pattern, in which the presence of a Democrat in the White House is associated with a tilt against welfare in public opinion (see figure). Aware of the negative implications of that pattern for his political fortunes, Clinton twisted arms in his party, and the reform ended up passing with a large majority – possibly a key factor saving Clinton’s chance for re-election in 1996.

Public opinion was very strongly against welfare as we knew it. If there was one thing the majority of Americans could agree on in 1996, it was that people on welfare were a big problem. The specifics were foggy, but on that much the majority seemed clear. In April 1996, 77 percent of Americans told the Gallup poll that taking action on welfare was either “very important” or a “high/top priority.” Seventy-one percent said they were for “cutting off federal welfare benefits to people who had not found a job or become self-sufficient after two years.”

After the bill passed, in August, 68 percent told Gallup they favored it, with just 15 percent opposed. Forty-nine percent said the “cuts in benefits to welfare recipients” were “about right,” and another 25 percent said they “do not go far enough.” That fall, 55 percent agreed with the statement, “Government should limit the amount it spends on welfare programs, even if some poor people do not receive assistance.”Work versus laziness, self-sufficiency versus dependence, these were the popular themes tapped to build support for the bill. These long-standing tropes in the dominant American culture were reinforced at the time by panic over high urban crime rates and Black violence (the Rodney King riots in Los Angeles occurred in 1992). Poverty, welfare, and crime, were bound up with race and racism by a tight web of highly-charged code words and concepts. For example, Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich wrote in 1995:

No civilization can survive for long with 12-year-olds having babies, 15-year-olds killing one another, 17-year-olds dying of AIDS, and 18-year-olds getting diplomas they can’t read.

In this popular view, the threat to America came from the urban Black poor. Cutting benefits to poor people who were perceived as Black, and discouraging (or punishing) what were perceived as their dependent and – frankly – crime-producing ways, was very popular. A 1995 New York Times poll found 79 percent agreed with the statement, “most people on welfare are so dependent on welfare that they will never get off it.”

The most fundamental reform idea – make them work

The marriage promotion components of the welfare reform – some of which were added after a few years – were not big parts of the debate at the time. That is surprising, given that the bill itself opened with a 1,200-word section titled Findings, which began, “Marriage is the foundation of a successful society,” and ended:

But marriage was only a signal of virtue, unmarried childbearing was its absence, and requiring work was a punishment for failure to abide by this norm. Work was not mentioned in the introduction to the bill, but it emerged as a key rationale. In a 2006 interview looking back at the welfare reform on its 10-year anniversary, Ron Haskins, a conservative policy advocate working at the Brookings Institution and an architect of the reform, did not mention increasing marriage rates as a goal of the policy. He said, “The most fundamental reform idea was that mothers on welfare, even those with young children, should be encouraged, cajoled, and, when necessary, forced to work.”“The most fundamental reform idea was that mothers on welfare, even those with young children, should be encouraged, cajoled, and, when necessary, forced to work.”Therefore, in light of this demonstration of the crisis in our Nation, it is the sense of the Congress that prevention of out-of-wedlock pregnancy and reduction in out-of-wedlock birth are very important Government interests and the policy [here] is intended to address the crisis.

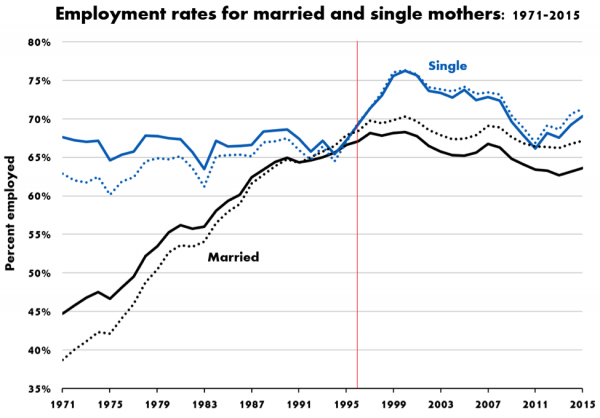

An under-appreciated factor in the shifting public opinion on single mothers and work was the massive increase in employment rates among married mothers in the three decades leading up to 1996. In an article Suzanne Bianchi and I wrote in 1999, we argued that there had been a major change in the popular view of women’s work accompanying that trend. Whereas welfare from the time of the New Deal had sought to help mothers remain out of the labor force – so they could raise their children – by the late 1990s mothers were increasingly expected to work for pay while their children were in paid childcare. And suddenly single mothers not “working” looked lazy compared with married mothers – especially middle-class married mothers, a rapidly growing and politically influential group – who increasingly were in the labor force.

Held up to the light of the trend, single mothers not employed became the object of newfound resentment. “Although welfare reform has concentrated attention on single women with children,” we wrote, “married mothers’ allocations of time to paid work also are central to the welfare debate, as these women often appear as a de facto comparison group.” The figure below illustrates the tension of that moment, showing the rapid convergence in employment rates between married and single mothers. (In the figure I show raw employment rates as well as rates at the mean of controls for age, education, race/ethnicity, and the presence of young children; this is to illustrate the trends are mostly not driven by changes in the composition of the two groups.)

Increasing hardship more than work

Although the number of single mothers was indeed increasing, it’s not that they were increasingly exhibiting laziness or dependence – leading to public scorn – it’s that married mothers were increasingly employed, making a non-employed mother appear outside the norm. With the White majority perceiving poor single mothers as mostly Black, this norm violation was received with outrage and condemnation.

The reform was successful at reducing the number of people receiving cash welfare, and as a result it probably did contribute to the increase in employment rates for single mothers – along with, of course, the very strong economy at the end of the 1990s.

Note that the rise in single mothers’ employment starting in 1994 predates the reform, which took several years after the 1996 passage before being fully implemented. And then when fully implemented, the welfare reform era saw an eight-year slide in single-mothers’ employment rates from 2005 to 2013. The timing of single mothers’ employment surges and declines undermines the idea that the welfare reform fundamentally altered the relationship between work, parenthood, and marital status for U.S. women.

Unnoticed at the time, married mothers’ employment rates stopped rising in the late 1990s after all, running into the barriers erected by poor work-family policy, men’s resistance to adopting women’s traditional roles, and a cultural shift toward “egalitarian essentialism” – the idea that women should be free to “choose” non-employment among other non-traditional options (as I argued in this essay).There is a sad irony here, one that is familiar to students of racial conflict in U.S. history. We had a moment in which single and married mothers – all moving toward higher employment rates – might have benefited from improvements in work-family policy for all families. This might have improved child well-being and reduced gender inequality at a time when women’s rising employment was reaching a limit under the existing policy regime. Instead, however, we ended up with a punitive policy directed at poor single mothers – and little progress on work-family policy for the next two decades.

If employment rates were not permanently raised, one lasting change produced by the welfare reform nevertheless was to increase the hardship and struggle for the poorest families, as has been demonstrated by Kathryn Edin and Luke Shaefer in their 2016 book, $2 a Day; and by Robert Moffitt in his 2015 presidential address to the Population Association of America. In the end, the reform may tell us more about dominant American attitudes toward poor people and their children – especially those who are Black – than it does about crafting social welfare policy for their benefit.

Comments