Since mid-March 2020, Gallup has been polling Americans about their degree of self-isolation during the pandemic. The percent who said they had “avoided small gatherings” rose from 50% in early-March to 81% in early April, dropping slightly to 75% in late April as pressures began rising to start loosening stay-at-home orders.

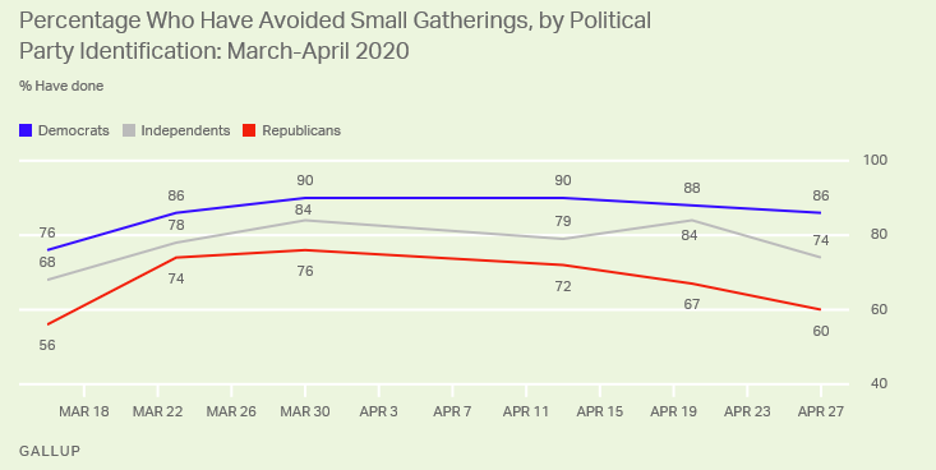

What makes this curve sociologically interesting is our leaders generally made the restrictions largely voluntary, hoping for social norms to do the job of control. Only a few state and local governments have issued citations for holding social gatherings. Mostly, social norms have been doing the job. But increasingly the partisan divide on self-isolation is widening and undermining pandemic precautions. The chart, which appeared in a Gallup report on May 11, 2020, vividly shows the partisan divide on beliefs in distancing as protection from the pandemic. The striking finding is the huge partisan gap with independents leaning slightly toward Democrats.

Not only did the partisan divide remain wide, but the number of adults practicing “social distancing” dropped from 75% in early April to 58%. This drop in so called self-reported “social distancing” occurred in states both with and without stay-at-home orders. Elsewhere I argue that “social distancing” is a most unfortunate label for physical distancing.

Republicans have been advocating for opening up businesses early, but it is not a mere intellectual debate. Some held large protests while brandishing firearms; others appeared in public without masks and without observing 6-feet distances. Some business that re-opened in early May reported customers acting disrespectful to others, ignoring the store’s distancing rules. In another incident, an armed militia stood outside a barbershop to keep authorities from closing down the newly reopened shop.

Retail operations in particular are concerned about compliance

to social norms because without adequate compliance, other customers will not

return. Social norms rely on social trust. If retail operations cannot depend

upon customers to be respectful, they will not only lose additional customers

but employees as well.

The Sad Impact of Pandemic Partisanship

American society was highly partisan before the pandemic, so it is not surprising that partisan signs remain. For a few weeks in March and April, partisanship took a back seat and signs of cooperation suggested societal solidarity.

We are only months away from the Presidential election, so we do not expect either side to let us forget the contest. However, we can only hope that partisans will not forget that politics cannot resolve the pandemic alone. Without relying heavily on scientists and health system experts, our society can only fail.

Unfortunately, lives hang in the balance if there is a partisan failure to reach consensus on distancing and related precautions. Economists at Stanford and Harvard, using distancing data from smartphones as well as local data on COVID cases and deaths, completed a sophisticated model of the first few months of the pandemic. Their report, “Polarization and Public Health: Partisan Differences in Social Distancing during the Coronavirus Pandemic,” found that (1) Republicans engage in less social distancing, and (2) if this partisanship difference continues, the US will end up with more COVIC-19 transmission at a higher economic cost. Assuming the researchers’ analytical model is accurate, the Republican ridicule of social distancing is such an ironic tragedy. Not only will lives be lost but what is done under the banner of promoting economic benefit, is actually producing greater economic hardship.

Ron Anderson, Professor Emeritus, University of Minnesota, taught sociology from 1968 to 2005. His early work centered around the social diffusion of technology. Since 2005, his work has focused on compassion and the social dimensions of suffering.