Flashback Friday.

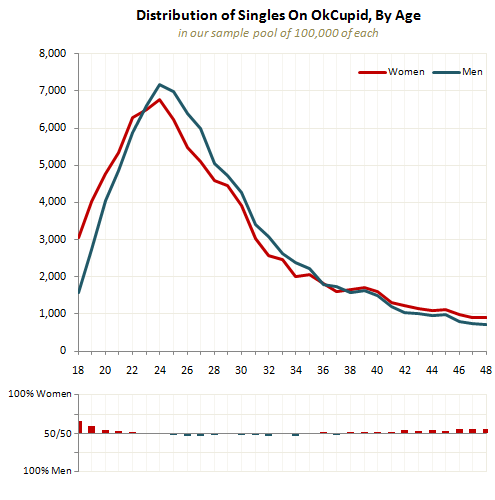

The number crunchers at OK Cupid recently looked at how age preferences disadvantage older women on the site. First, the post’s author, Christian Rudder, points out, the distribution of singles is pretty matched by sex at most ages:

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that women and men of the same age are reaching out to one another.

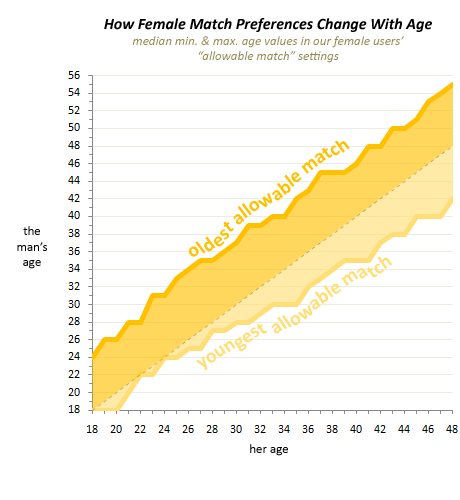

Women at most ages state a preference to date men who are up to eight years older or eight years younger:

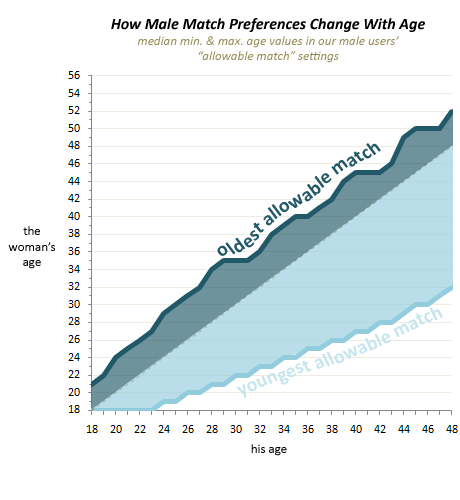

But men show a decided preference for younger women, especially as the men get older:

But men show a decided preference for younger women, especially as the men get older: And, Rudder notes, men target their messages to women even younger than their stated preference. In this figure, the greenest areas represent where men are sending more messages and the red areas are where they are sending less:

And, Rudder notes, men target their messages to women even younger than their stated preference. In this figure, the greenest areas represent where men are sending more messages and the red areas are where they are sending less:

So, even though men and women are more-or-less proportionately represented on the site, men’s decided preference for younger women makes for many fewer potential dates for older women.

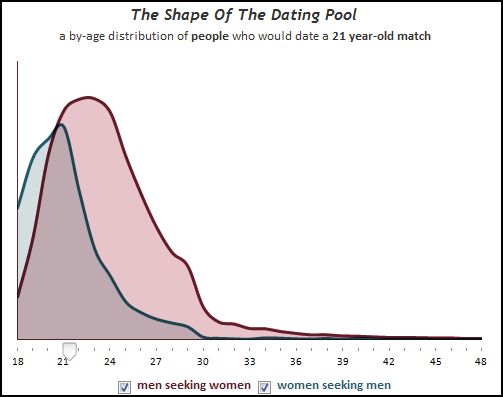

Here’s what the dating pool looks like for 21-year-olds (the blue = men seeking women who are 21; the pink = women seeking men who are 21):

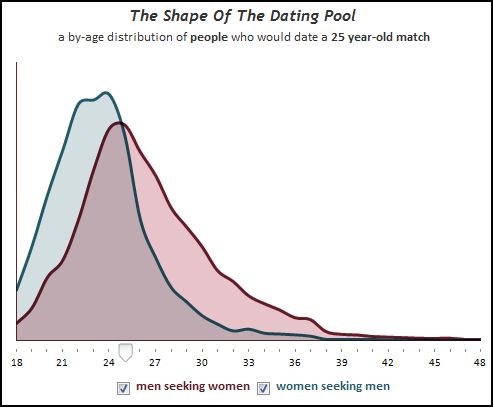

For 25 year olds:

For 30 year olds:

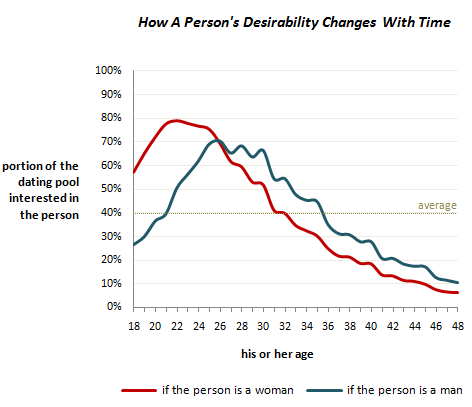

Rudder offers this summary measuring how a person’s desirability changes over time:

He writes:

…we can see that women have more pursuers than men until age 26, but thereafter a man can expect many more potential dates than a woman of the same age. At the graph’s outer edge, at age 48, men are nearly twice as sought-after as women.

Thus opportunities for dating are shaped by the intersection of gender and age to the detriment of women over 26 and men under 26.

Originally posted in 2010.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.