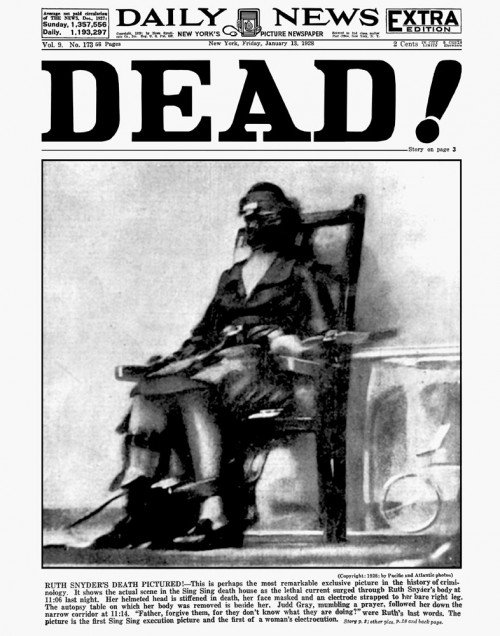

In 1928 readers of the New York Daily News were shocked by this cover. It was the first photograph ever taken of an electrocution.

The executed is a woman named Ruth Snyder, convicted of murdering her husband. The photographer was a journalist named Tom Howard. Cameras were not allowed in the execution room, but Howard snuck a device in under his pant leg. Prison officials weren’t happy, but the paper was overjoyed.

The fact that the image was placed on the front page with the aggressive headline “DEAD!” suggests that editors expected the photograph to have an impact. Summarizing at Time, Erica Fahr Campbell writes:

The black-and-white image was shocking to the U.S. and international public alike. There sat a 32-year-old wife and mother, killed for killing. Her blurred figured seemed to evoke her struggle, as one can imagine her last, strained breaths. Never before had the press been able to attain such a startling image—one not made in a faraway war, one not taken of the aftermath of a crime scene, but one capturing the very moment between life and death here at home.

It is one thing to know that executions are happening and another to see it, if mediated, with one’s own eyes.

Pictures can powerfully alter the dynamics of political debates. Lennart Nilsson‘s famous series of photographs of fetuses, for example, humanized and romanticized the unborn. They also erased pregnant women, making it easier to think of the fetus as an independent entity. A life, even.

Unfortunately, Campbell’s article doesn’t delve any further into the effect of this photograph on death penalty debates. To this day, however, no prisons allow photography during executions. What if things were different? How might the careful documentation of this process — with all our technology for capturing and sharing images — change the debate today? And whose interests are most protected by keeping executions invisible?

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Comments 10

historydragon — May 12, 2014

Executions used to be completely public events. They basically turned into fairs, complete with people selling food and souvenirs (and occasionally disrupting the proceedings) and people throwing things at those to be executed (or jumping up to drag their bodies off the dock to keep them from being used for anatomical or surgical study). They became private and contained in large part out of a desire to contain that kind of thing. So at least one possibility is that we'd be much worse off for it, and watching today's convict getting killed would become a social events.

DavidGLamb — May 12, 2014

Cameras were not allowed in the execution room, but Howard snuck a device in under his pant leg. http://sn.im/28wjrxn

Elena — May 12, 2014

It is one thing to know that executions are happening and another to see it, if mediated, with one’s own eyes.

Centuries of public hangings, beheadings, drawing and quarterings, burnings at the stake, breakings of bones at the wheel, and so on, say it doesn't make an ounce of difference if the execution is a private electrocution or if they're eviscerating the condemned and burning their entrails in front of them before hanging.

(I lie, public executions of people hated by the commoners were parties where you had to book balcony seats in advance)

Sociopress.cz » Moc fotografie: „MRTVÁ!“ — June 5, 2014

[…] WADE, Lisa. Dead! Execution and the power of photography. Sociological Images [online]. 2014 [cit. 2014-05-28]. Dostupné z: http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2014/05/12/dead-executions-and-the-power-of-photography/ […]