Cross-posted at Jennifer Carlson’s Blog.

In national gun debates, we often think about America as “divided” geographically along the issue of guns. USA Today recently reduced the American gun debate to “urban vs. rural,” saying that “[o]ne of the biggest factors in where you stand on gun ownership and gun violence depends, literally, on where you lay your head at night.” This captures an important truth about American gun politics, but relying too much on the rural/urban divide across states obscures how this plays out within states.

The urban/rural divide in gun cultures suggests that guns are a necessary and practical tool for rural Americans who need them for the purposes of hunting, self-protection, and so forth. But these same factors should become irrelevant in the urban setting: between supermarkets and public services (combined with denser living), urbanites should see guns either as a hobby (for some urbanites) or a hazard (for most urbanites) rather than a practical tool of everyday life.

Following this logic, public law enforcement officials in urban areas should also oppose gun rights, and in fact, many do. Ken James, police chief of the Emeryville Police Department and head of the firearms task force of the Police Chief’s Association of California, recently called the notion that guns are defensive weapons a “myth” has said in the past that he prefers that his officers do not carry guns off-duty. Likewise, a number of national police associations have come out in support of Obama’s gun control proposals. In contrast, over 400 county sheriffs have publicly stated that they will not enforce any “unconstitutional” laws signed by the Obama administration. Perhaps the rural/urban divide is driving gun politics.

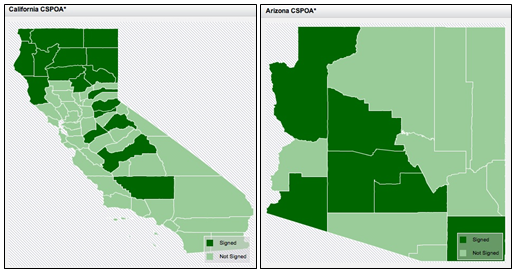

But maybe not. Let’s take a closer look at the county-level politics of gun control attitudes in California, a state with some of the most restrictive gun laws in the US, and Arizona, a state with some of the most permissive laws.

Interestingly, both states have roughly the same number of counties with sheriffs that have aligned themselves with this pro-gun platform: in Arizona, 40% of county sheriffs have signed on, while in California, this figure is 31%. These numbers aren’t that different, considering how different their gun laws are. But here’s where it gets interesting: the expected urban/rural divide appears in California, but not Arizona, where urban counties have more pro-gun sheriffs. What this means is that the rural/urban divide — at least in terms of sheriff support for gun rights — is flipped between gun-phobic California and gun-crazed Arizona.

No doubt, these two maps raise the question of how other issues intersect with, and structure, gun politics: for example, the politics of immigration likely have much more to say about the differences between Arizona and California than any straightforward divide between rural and urban America. Indeed, these maps suggest that there are logics about the role of guns in the pursuit of social order and policing at work in California versus Arizona that are not captured by neat dichotomies between “rural” and “urban” Americans.

Jennifer Carlson, PhD is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Toronto. She is working on a book manuscript entitled, “Clinging to their Guns? The New Politics of Gun Carry in Everyday Life.”

Comments 7

fredschumacher — June 22, 2013

One factor operating on Arizona may be that it has a large population of rural people from other states, especially northern ones, who have retired to or winter-over in urban Arizona. Sometimes it feels as if half of North Dakota's over-70 population is in Mesa, Arizona during the winter.

Yrro Simyarin — June 22, 2013

Tracking the position of local police chiefs doesn't get you any farther than tracking the political positions of local legislators. It's a political position more than a professional one in almost all jurisdictions. You see significant variance between polling of police chiefs and polling of rank and file officers on this and many other issues where people think that police have a unique perspective.

[links] Link salad loves days with names that end with a “Y” | jlake.com — June 23, 2013

[...] Is Gun Control a City vs. Country Debate? — Huh. This is less clear cut than I would have expected. My bias is showing again. [...]

CassandraP — June 24, 2013

You appear to be using "Arizona" as a shorthand for "Phoenix" in this post, which is a bit awkward. There are six counties in Arizona that have approved notably permissive gun laws; four of them are indisputably rural, and a fifth (Pinal) is arguable at best. There are nine counties that haven't approved the new laws, and again, most of them are overwhelmingly rural. The largest cities in Arizona besides Phoenix are Tucson (Pima County, pro-gun control) and Flagstaff (Coconino County, also pro-gun control).

The question should probably be rephrased as "Why does the city of Phoenix believe that guns will make them safer, when most other metro areas appear to believe the opposite?"

caryatis — June 24, 2013

You can't refute evidence about what Americans think with evidence about the political positions of sheriffs.

Is Gun Control Really an Urban vs. Rural Debate? — August 9, 2013

[...] post originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner [...]

Sharon Keels — January 29, 2021

This topic excites me very much and I am always pleased when I see what is being said about it. First of all, I want to say that most people do not know this, but 95% of the weapons used in the US during mass shootings can be legally bought in Canada. You can learn more about this from the article https://faze.ca/gun-control-canada-vs-usa/, which is entirely devoted to this topic. You may be aware that in the United States, background checks are not always a prerequisite before buying a rifle.